Domesday Redux: The Rescue of the BBC Domesday Project Videodiscs

Origins

William of Normandy, having conquered England, decided in 1086 to take account of his new territory. The result was the Domesday Book (actually more than one), which now resides in the National Archives [1]. For the BBC, the 900th anniversary in 1986 presented an opportunity to produce a television series, hosted by Michael Wood. A more unusual production was to use the combination of computer and video known as interactive video to produce a kind of modern-day equivalent of William’s survey.

In 1983, a BBC Television producer named Peter Armstrong, now director of OneWorld International [2], had wondered if it would be possible to harness the Domesday philosophy to modern Britain. He originally envisaged an interactive documentary and soon found that interactive video was limited in the volume of moving pictures it could carry - but there was room for tens of thousands of still images. With the large user base of microcomputers in British schools (helped by a government subsidy) it was feasible to ask schools around the UK to survey their areas to produce a database of how Britain looked to the British in 1986. Combine this with thousands of maps, still photographs and central statistical, written and visual information and you have the basic structure of the 1986 Domesday Project.

This was clearly much larger an undertaking than even a television programme. So a distributed team was assembled including statisticians at the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, software expertise from Logica and video facilities at the BBC Open University Production Centre (OUPC), as well as a core team based in an obscure BBC outpost in West Ealing. An Editorial Board was set up, chaired by Peter Armstrong, and negotiations were started with outside sources such as the Ordnance Survey, newspaper publishers and photo libraries. A photographic competition was launched, which would eventually net thousands of photos (and was won by an image that was notoriously difficult to show cleanly on television). And, through contacts in BBC Education, a plan was devised to ask thousands of schools around the UK to survey, photograph and write about their neighbourhoods.

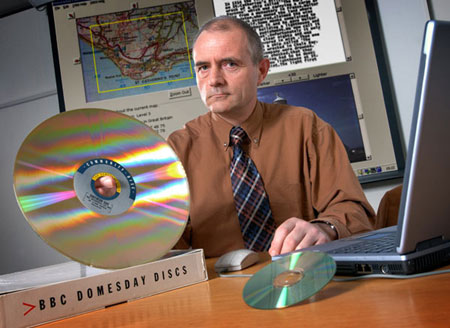

Peter Armstrong, Head of the 1986 Domesday Project

with Sarah Tyacke, Keeper of the Public Records

Europe Chips In

Some funding for the project was to come from the BBC, but half of the money came from the European Commission - as part of its very first Framework Programme for Research (FP1). Philips Electronics were one of the companies behind videodiscs, in their case called LaserVision. They were brought into the loop, as were BBC Research at Kingswood Warren in Surrey. Philips offered a new variant of LaserVision, to be called LV-ROM. It was possible to replace the part of the baseband signal normally used to carry audio by a data channel - later versions of videodiscs used this channel for digital sound. For the Domesday team this offered a more stable solution than the full-frame teletext they had originally considered, and Philips were sure that the resulting players would be priced so that schools could easily afford them. At this time there was no such thing as CD-ROM; when this appeared its data storage parameters were to be very similar to LV-ROM. Although the Domesday data was held digitally on the videodiscs, the audio and video were analogue, the video being standard 625-line PAL (Phase Alternating Line) format.

It was decided to break the project into two parts: the Community Disc and the National Disc. The National Disc was to contain national statistical information (which could be displayed interactively as charts or mapped onto the user’s choice of map), sets of photographs reflecting all aspects of British life, items from newspapers and magazines, some non-immersive virtual reality tours around diverse locations and a short set of movies documenting the decade so far. The Community Disc was based around blocks of land, four kilometres by three, onto which the collected data, text and photographs were arranged. The maps for these blocks were from the 1:50 000 OS mapping. The user could navigate around these maps by clicking on the screen: itself something of a novelty in the mid-1980s. There was also information matched to maps at both larger and smaller scales, right up to ‘global’ essays about the British regions and the UK as a whole. At ‘higher’ levels than the basic four-by-three blocks, users could see aerial photographs and also satellite images aligned to match the map itself. There were other means of navigation for both discs, the most important being a free-text search system based on an innovative algorithm by Dr Martin Porter [3].

Sending out the Scribes

For the Community Disc a data collection template was produced by the BBC team and sent out to schools on floppy discs and on cassette tapes. (Audiocassettes were a common way of storing data for home computers since floppy disc drives were very expensive at the time.) The project wanted three photographs per school, up to 20 teletext-sized screens of text about the area and some survey information. The introduction of a national curriculum and a teachers’ work-to-rule restricted the opportunities for schools and as a result much of the work was done by primary schools and considered to be local studies.

The BBC team collated the community data and the photos were sent to the OUPC for transfer to video, as were the maps. The OUPC had a special kind of videotape machine that was designed for the production of videodiscs and allowed the recording of individual frames, one by one. Since television is a moving medium, there were severe technical challenges in doing this reliably in an analogue world. The photographs were transferred one by one using a telecine machine with a 35mm transparency facility. The maps, which were actual paper maps bought from the Ordnance survey, were laid flat under a rostrum camera and similarly transferred to analogue videotape. All the images were transferred to tape following a carefully worked-out algorithm, which was set up to make access and display easier. All this video content was assembled in batches and then edited onto a master tape for each disc side by the OUPC. BBC Enterprises produced the side of the National Disc that held the news movies.

Software Development

The data retrieval software was written by the Logica team using BCPL (Basic Combined Programming Language)[4], a precursor to C. The software on the disc is made up of compiled intermediate code that runs in a virtual machine on the BBC and RM (Research Machines) computers. The Logica team was led by Jardine Barrington-Cook, who recalls how exciting the project was for the computer people who worked on it. Advanced new ideas were being shoehorned into the tiny BBC processor, which had so little memory that a block of 256 bytes, initially kept in reserve, proved to make a serious difference to getting the system to work. The data organisation was specially designed to provide rapid access within the limited resources available. The enthusiasm was such that people were working night and day and sleeping in the office.

At the same time, large teams of people at the UK Data Archive [5] at Essex University, the Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies [6] at Newcastle University and units at Birkbeck and Bangor were working on the data for the National Disc. It started as government statistics covering the whole country, which were re-processed to fit the Domesday grid of kilometre squares. This made area-based data from different sources directly inter-comparable in ways that the source data’s incompatible spatial units prevented, potentially opening up local and central government policies to challenge by the public. This processing required a large amount of computer capacity, and many of the University computers on the JANET Network [7] were pressed into service - some of them for free, since charging systems were limited at the time. The data was collated into large data files (basically ASCII text-based and using simple tagging procedures), which were transferred onto half-inch ANSI data tapes using the Domesday team VAX mini-computer [8] in Ealing. These tapes and a copy of the master tapes were sent to Philips’ Dutch factory in Eindhoven where the videodiscs themselves were produced.

Delivery Systems

The Domesday delivery system consisted of a BBC Master Microcomputer with co-processor, the videodisc player and a monitor. The micro was a standard machine with three additions. There was a SCSI card [9], which communicated with the player for data transfer and control, there was a special filing system chip, known as the VFS-ROM (Videodisc Filing System-Read-only memory), so that the player would look like a big read-only floppy disc as far as the computer software was concerned, and there was a trackerball with which the user could move a pointer around the screen and click to action selections. There was also a configuration for the Research Machines micro that was also used in schools. It was not technically possible to use a Sinclair Spectrum [10], which was the third type of schools computer.

The BBC Domesday Project system, comprising a BBC Master

and a specially produced LV-ROM

BBC Enterprises published the discs in November 1986. They were available as a package together with the necessary hardware for around £4,000, which made them a little expensive for many schools and over twice what the project believed they were to cost. By this time the British government had changed its policy from subsidising hardware in schools to subsidising software. The best efforts of Philips and Acorn and even the help of ESPRIT funding from the European Commission could pare the cost down no more. After a while, a company called Cumana found a way to offer Domesday Systems at a lower price and more were sold. The targets were schools, universities and libraries. The project was seen as a success in every way except its sales, although the security services were a little concerned about the ease with which national data was now available. The project was visited by MI5 and was presented personally to the Prime Minister Mrs Thatcher.

Loyd Grossman with a videodisc of the Domesday Project,

at the launch of the Digital Preservation Coalition, February 2002

Enter The National Archives

The National Archives first became interested in the preservation of the BBC Domesday videodisc data at the launch of the Digital Preservation Coalition [11] at the House of Commons on 27 February 2002. At that event, the UK broadcaster Loyd Grossman spoke of the danger that the rapid evolution of computer media and record formats would lead to the irretrievable loss of valuable historic records, and gave the Domesday discs as an example. Back at the office, Jeffrey Darlington found that the BBC Domesday system presented to the Keeper of the Records in 1986 was still in working order, and it was agreed that its collection of images, text, maps and datasets should be preserved for posterity. The National Archives then made contact with the CAMiLEON Project [12] and other parties who were interested in rescuing the Domesday data.

A Divergence of Views

Andy Finney, the videodisc producer on the original project, described his plan to track down the best surviving copies of the master analogue videotapes from which the videodiscs were produced, and to convert the images into a modern broadcast-quality digital format. We discussed this plan with the CAMiLEON team, and a difference of opinion emerged. The purpose of the CAMiLEON project was to demonstrate the value of emulation in preserving not only the data stored in obsolete systems but the behaviour of the systems themselves - in this case one of the very first interactive multi-media systems. The aim was to reproduce the original user experience as accurately as possible, and the CAMiLEON team argued that the slight faults in images as displayed from the analogue discs were a part of that experience, and should not be cleaned up as Andy proposed to do. Our aim was different - we wanted to preserve the data with the highest quality available consistent with longevity.

An analogy in the world of music is the difference of opinions on whether to play Bach on the piano. The purists argue that since the piano did not exist when the music was written, it should be played only on the harpsichord or other instrument from that era, building new harpsichords as and when required. Others argue that if Bach had ever heard a piano he would be delighted with the new and richer sound, and therefore it is OK to play his music on the piano and give listeners a different experience. These schools of thought co-exist, and while agreeing with the value of the CAMiLEON approach we preferred to support Andy’s high-quality preservation of the data. The question of how to present the material to present-day users remained to be solved. One approach that was considered was to run the original CINT code in a virtual machine migrated to a PC platform. This remains an interesting possibility for future research.

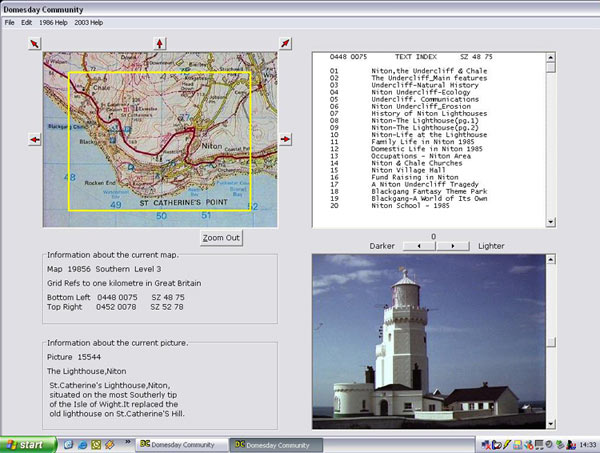

Convergence at Leeds

The CAMiLEON emulator was demonstrated on 2 December 2002 at an event at Leeds University, using Domesday data grabbed from the videodiscs by a PC interfaced to one of the surviving LV-ROM (LaserVision Read Only Memory) drives. At this event, Jeffrey and Andy met Adrian Pearce for the first time, and saw a prototype of his new interface to the data from the Domesday Community disc. This data is organised geographically using maps of the UK at several levels, each map being linked to up to 20 screens of text and up to 7 pictures. The user can zoom in and out, and move around the country at each level, looking at the maps. On the original system, limited to a TV screen resolution, the user can then call up the pictures and text separately. Adrian had realised that on a modern platform the identical organisation could be used - but with maps, text and pictures displayed simultaneously in three different panes. The fourth quarter of the screen could show the first-level context-sensitive help including map references and the picture captions and descriptions. We all agreed that this was a new realisation of Peter Armstrong’s original vision. The National Archives then obtained approval from the copyright holder BBC Worldwide [13] to put a re-engineered version of the Domesday system on public display.

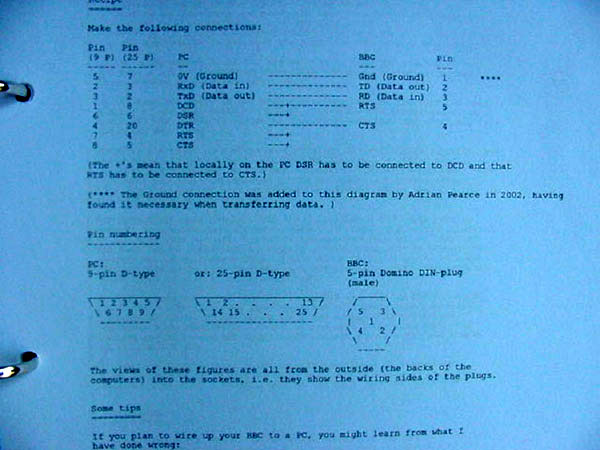

Screenshot of the new system

The Domesday Project [14] made a lasting impression on many people who took part including Adrian’s wife Sally, who led one of the data collection teams with a group of teacher training students from the University of Brighton. It was her suggestion in December 2001 to make the Domesday Community data available on Windows PCs for her current generation of undergraduate students. A complete BBC Domesday system had been stored away at Brighton and Adrian found that it still worked well. He had no technical documentation for the system, and started by listing the file directory of the Community disc. He then connected the BBC micro to a PC via the BBC RS423 and the PC RS232 sockets. This made it possible to download the digital files from the ‘audio’ data channel on the disc. The stress of long downloads (over 50 hours per file in some cases) soon caused the BBC motherboard to fail. Fortunately it proved possible to obtain replacements for the motherboard and SCSI interface board. The download yielded over 300MB of text and hexadecimal data, together with the BCPL-compiled programs.

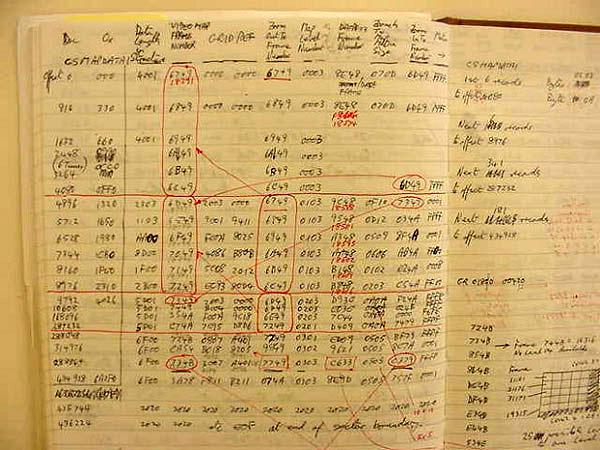

Reverse engineering: slowly unpicking the hexadecimal puzzle

Re-creating the Application

Adrian then set out to decipher the data structures using a hexadecimal editor, like an enormous hexadecimal crossword. Data structure books of the period indicated the style of tree structures being used, and familiarity with the operation of the original system helped to understand them. Adrian also needed the ability to see hexadecimal patterns, and to think how he might have solved the same problem in 1986 with the languages and data structures of the day. The Community Disc has similar but different trees on each side representing north and south. The data incorporates geographic grid references in three systems: British, Irish and French. The British and Irish have numeric, alpha numeric and alpha representations, some of which are the same in the two systems but refer to different places. The Community data handles all these variations, but finding out how was another puzzle. All the system keywords in the index trees used by the search algorithms were stemmed; fortunately Dr Martin Porter had recently published a C implementation of his original word-stemming algorithm, and this formed the basis of Adrian’s new search algorithms.

A custom specification for a cabling to connect the BBC Master to a PC

For the video data, Adrian started to frame-grab images from the videodiscs using an RGB frame grabber [15] card in a PC, and a custom cable to connect to the RGB output of the videodisc player [16]. This approach has been used in other resurrection projects, but it takes a lot of time to download thousands of images, and it does not give the highest quality for a number of reasons - some to do with the nature of PAL television and some with the inherent problems of videodisc. After Adrian had grabbed a sample of images sufficient to test out his new system, he agreed to use images derived from the original videotapes that Andy Finney was tracking down. The earliest copies of the tapes turned up in Peter Armstrong’s loft.

Preserving the Content

The migration of the image content from the analogue videotapes was a two-pronged approach. It was decided to re-archive the video material in a digital video format and also make JPEG images available for the PC version. The 1-inch analogue videotapes were digitised at BBC Research and transferred onto Digital Betacam (arguably a safe format for another ten years or so) for archiving with both the National Archive and the BBC, and onto an intermediate DV (Digital Video) format that enabled Andy to batch-process the tens of thousands of images on the Community disc into individual JPEGs using desktop computer equipment. The PAL ‘Transform Decoder’ has been an important part of the BBC’s digitisation of its archive, and it was specially modified to cope with Domesday’s individual frames. This innovative work in decoding and digitising legacy PAL material, and the retention by the BBC of the ability to play back the 1-inch tapes properly, have been key factors in rescuing the image data. (For more details, see Andy Finney’s Web page)[17].

The resulting images of both maps and photographs are noticeably better in quality than those on the videodiscs. The National Archives have now installed Adrian’s system with these high-quality images in their library at Kew and made the Community data available to the public on a modern platform.

Conclusions

The rescue project came just in time. A working original system to compare with and validate the migrated system is invaluable, especially in multimedia migration where the look-and-feel and user interaction is important. Some original systems and hardware components were still available and could be made to work, but the systems were fragile. Wear between the videodisc drive spindle and the disc has caused the loading of the disc to be a delicate operation on most systems.

Adrian Pearce, the developer of the 1986 Domesday Community

Adrian was in the fortunate position of having access to an original system in working condition, the time to work on the problem for as long as it took and a relevant software development background. Understanding data structures in hex requires an aptitude for observation and pattern matching but is quite satisfying as long as there is no deadline. The timescale was unknown at the outset, and it eventually took sixteen months to produce the new Windows version.

The lesson of this digital preservation project is that if you have enough time, individual skill, dedication and imagination then almost anything is possible, provided that you don’t leave it too late. If you start counting the cost this may seem an expensive project, but then the value of the record is high too - and that applies equally to the original Domesday Project. There is of course a great need to preserve other electronic records in a routine and predictable manner, and this rescue project is not a suitable model to be followed in such cases. The National Archives is working on ways to make this possible in future.

Andy Finney says: “If I personally have one regret about Domesday it is that many of the people who contributed to it never got to see the results of their efforts. For that reason alone I am delighted to see it more widely available now that the real world has caught up with our technological vision. Dare I hope it will be republished by the BBC?”

References

- The National Archives http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

- OneWorld International http://www.oneworld.net/

- Martin Porter’s Home Page http://www.tartarus.org/~martin/

- Information on BCPL http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/BCPL_programming_language

- The UK Data Archive, University of Essex http://www.data-archive.ac.uk/

- Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, Newcastle University http://www.ncl.ac.uk/~ncurds/

- The JANET Network http://www.ja.net/

- Information on VAX (Virtual Address eXtension) http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/VAX

- Information on SCSI Small Computer System Interface http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/SCSI

- Information on the Sinclair ZX Spectrum home computer http://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/ZX_Spectrum

- The Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) http://www.dpconline.org/graphics/

- Creative Archiving at Michigan & Leeds: Emulating the Old on the New (CAMiLEON)

http://www.si.umich.edu/CAMILEON/ - BBC Worldwide http://www.bbcworldwide.com/

- The Domesday Project http://www.domesday.org.uk

- RGB Frame Grabber, Introduction to Frame Grabbers http://www.theimagingsource.com/prod/grab/grabintro_2.htm

- The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Mark de Weger and Angus Duggan for the XFER3 and 4 software and cable design.

- Preservation & Emulation - Domesday Redux, Andy Finney,

http://www.atsf.co.uk/dottext/domesday.html#redux

Author Details

Jeffrey Darlington Email: jeffrey.darlington@nationalarchives.gov.uk |

Andy Finney Email: andy@atsf.co.uk |

Adrian Pearce |

Article Title: “Domesday Redux: The rescue of the BBC Domesday Project videodiscs”

Author: Jeffrey Darlington, Andy Finney and Adrian Pearce

Publication Date: 30-July-2003

Publication: Ariadne Issue 36

Originating URL: http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue36/tna/