A National Archive of Datasets

The National Archives has been building up a collection of UK Government datasets since 1997 under a contract with the University of London Computer Centre (ULCC) [1]. The archived datasets are available to users free of charge through the World Wide Web and are known as the National Digital Archive of Datasets (NDAD) [2].

Datasets are one of the earliest types of digital record produced by Government departments, some of those now archived dating back to 1963. The appraisal and selection of datasets is done by the National Archives, working together with the departments that created them. They cover a wide range of subjects, a few examples being:

- Ancient Woodland Inventory

- North Sea Geographical Information System

- Public Health Common Data set

- Digest of Museum Statistics

- British Crime Survey

Ancient Woodland Inventory

An inventory of woodland sites over 2 hectares in England which are thought to have been in existence since at least 1600 AD. The AWI was begun by the Nature Conservancy Council in 1981 and has been continued by its successor, English Nature. The data gathered includes the name of the site, its location, the current area, the area cleared of woodland since surveying was conducted for the Ordnance Survey First Series 1:25,000 maps, the areas of ancient semi-natural woodland and ancient replanted woodland, and whether the site is associated with a Site of Special Scientific Interest. NDAD currently holds a single dataset consisting of AWI data extracted from English Nature's information system in 2001-2002.

Figure 1 : The Ancient Woodland Inventory

Like other public records, datasets are selected for permanent preservation because of their potential future value as part of the nation's memory. The National Archives has a published acquisition policy [3] implemented through published Operational Selection Procedures that explain the criteria for selection. The selected datasets are preserved and, subject to restrictions on access for reasons of confidentiality, are made available for public use through the Web.

The potential users are of two kinds. One kind typically analyses large sets of records by statistical methods. The other is the kind of user who wishes to search for a small number of records by the name of a person, place or organisation. These include family history researchers, who have become the most numerous users of digital data in recent years, and for whom the National Archives provides data resources including the Documents Online [4] and Access to Archives [5] Web sites. At present, users of the national dataset collection are mainly of the first kind, since those records that are of interest for family history are not yet open for access.

Many important datasets at NDAD are closed for 30 years or more. These closed datasets are kept in a secure section of the archive and preserved for re-use by future users, the National Archives having recognised that digital records will not be readable after 30 years without taking active steps to preserve them. The advent of Freedom of Information in 2005 may result in some datasets being released to the public much earlier than originally intended, though it is likely that personal data will remain closed for 100 years. The archive will increase in value as a resource for users as these restrictions expire in future years.

Decisions about access rights are complex. It is not just a matter of protecting the privacy of personal and corporate data. Information about the natural environment may also be sensitive; people who illegally collect wildlife or wildlife products could misuse knowledge of the habitats of rare species if it is freely distributed.

Users of the Archive

At present researchers from the academic and business worlds are the main users of the open datasets. Social and political scientists are established users (and sharers) of structured data, re-analysing for example the survey data used to support Government decisions; their analysis is typically numerical and statistical. The archive also provides a helpful data source for students of the natural environment and of education. Historians are not great users of numerical data at present, but we may expect that in time they may take more interest in digital records and statistical methods. It is also expected that Government users will become more active in analysing their own historical data in future. The North Sea GIS and some other datasets are of significant and obvious business interest.

All open datasets are available for on-line browsing, and users can create subsets of data through a query processor, for viewing and for downloading to their own computers for further analysis. A comprehensive on-line catalogue explains both the context and the content of each dataset, and describes the tables and columns included in them. Codes used in the datasets are held in their original form, with an instantly accessible explanation of the meaning of each code and the values it takes (the codebook). When browsing a dataset, codes are either expanded or left in their original form at the user's choice.

Many datasets come with extensive documentation that is essential to understanding the meaning of the data, and for some types of research may be more important than the data itself. Often there is a published report based on the dataset. Other documentation may include copies of questionnaires or a user manual - and when the dataset has a geographical dimension, maps. In some cases we even hold listings of COBOL programs as a record of processes included in the original system. All these items of documentation are also held in digital form and are catalogued and made available (if open) for browsing and downloading. The archive's catalogues of data and documentation conform to international standards, and can be accessed from the National Archives' own catalogue as well as from the NDAD Web site.

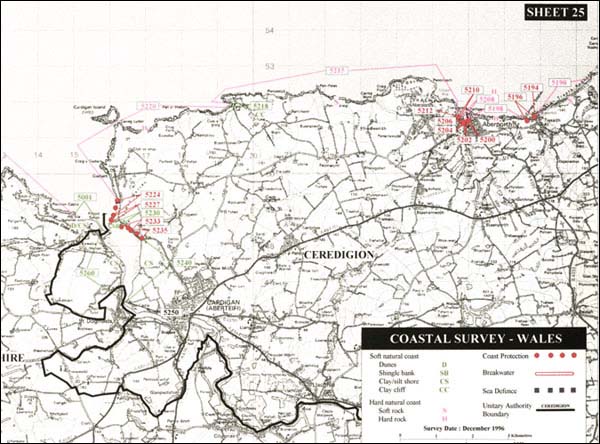

Figure 2: Map from Welsh Coastal Survey

Preservation Strategy

The physical preservation of datasets is based on a high-capacity automated tape library system that provides a very high level of reliability and security. Multiple copies are kept, on-line and off-line. Periodic checks are made by the system to see if any tape has passed a defined maximum age or accumulated usage. In addition, over a six-month period at least one copy of every file stored is automatically verified for readability, and over a period of 18 months, every single tape that contains data is checked for readability.

Each dataset is stored in a simple linear format based on open standards. The common format has a minimum of hardware and software dependencies, making it relatively 'future proof'. Statistical datasets consist essentially of collections of simple tables of data values, and this structure is accurately captured in the common format when accompanied by suitable metadata. Even though the standards on which it is based could become obsolete in time - for example, the 8-bit ISO 8859-1 character set may be superseded by Unicode - forward migration is assured, and the common format is easily imported into the proprietary formats of successive generations of analysis software.

Many users of digital datasets are interested in comparing figures over long time periods that may have originated in different studies using different data formats, and conversion to a common format is helpful to them. Many other national archives use similar formats, as do academic archives of research results in social and political sciences. In future, as more complex collections of data are archived, the strategy will be adapted to deal with them, based always upon open standards.

Many Government datasets are produced using one of the common statistical survey packages such as SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Other datasets come from 'retired' Government systems that maintain operational databases, sometimes in historic formats like IDMS (Integrated Data Management System) or Adabas. These are more difficult to preserve, because they support more complex data relationships, and often include standard queries and 'views' of the data, which are not captured in the flat file format. Their metadata conforms to a wider range of standards than those for statistical data. When such databases are proposed for transfer to NDAD, data tables are extracted and converted to the standard preservation format. In this way only the data tables are preserved, but on the other hand researchers can then view them without having to hold a wide variety of database licences for obsolete products.

The original record format is documented in the dataset catalogues, along with details of the original system and the hardware and software environment in which it operated. The process of conversion is also documented and any deficiencies found in the data are listed. The Swiss Federal Archives has commissioned a software package called SIARD (Software Independent Archiving of Relational Databases), which promises to preserve queries and views in the standard SQL database language, along with the data tables and standardised metadata - an ambitious aim. The approach uses a combination of XML (Extensible Markup Language) and standard SQL. This software will be made available to other national archives and will provide an improved preservation strategy, at least for the range of currently popular relational database products. The National Archives is participating in the testing of SIARD.

Preservation Challenges

Some of the datasets being archived now are relatively new, in some cases still being available in whole or in part on the website of the originating agency. Early selection and early archiving has the great benefit of insuring against the loss of data, of documentation, and of expertise when the dataset goes out of operational use. That this is a very real danger is illustrated by the problems encountered in archiving older datasets.

In some cases these have been stored on their original magnetic tapes for decades, a preservation strategy not to be recommended. The tapes deteriorate and may become completely unreadable. At best they may be readable at a slow speed, and even then portions of the data may be lost beyond recovery. Nevertheless, we have managed to recover data from some 30 year old tapes, only because three copies of each tape were kept, and we were able to piece together a complete set of the data by reading different segments from different copies. It goes without saying that a digital archive must have a tape drive for reading 9 track open reel tapes. Despite its exceptionally long life as a standard interchange medium, this is a historic format and manufacture of the drives has now ceased.

This term covers a range of processes that may be employed in the preservation of data:

Conversion from one software format to another, for example Word to PDF.

Conversion from one character code to another, for example EBCDIC to ASCII.

Transfer from one physical medium to another, for example an old magnetic tape format to a newer.

Copying a file to fresh media of the same kind, more appropriately known as media refreshment.

In other cases datasets from as far back as 1963 have been received from the originating agency (or its successor) on a modern tape medium, the data having been migrated through successive generations of computer systems at the agency. This approach alleviates the troubles attendant on dealing with obsolete physical media, but in their place brings problems of its own. In some cases data has been lost in previous migrations; it is important to guard against this possibility by checks against the documentation. On one occasion it was found that the totals in the published report (supplied with the dataset) did not tally with totals derived from the digital records. It turned out that a mistake in tape handling in one migration had caused about a thousand records to be lost forever. It proved possible with help from the agency to reconstruct a summary of the missing records in this case.

The transfer medium most frequently encountered at present is the compact disc. Transfers on obsolete types of floppy disc are now quite rare, although a variety of disc and tape media are still supported.

Digital Archaeology

Normally some care has been taken to avoid actual data loss during migration. Preservation of the metadata that defines the meaning of the data has not always been so rigorous, especially for older datasets. An example of this occurred with the earliest digital records of the Schools Census [6]. This survey of schools in England and Wales is believed to have been started in about 1946 and first recorded on computer media around 1975. The datasets transferred to NDAD are normally in the file format of Qstat, the survey software used by the Government's educational statisticians. A small number of records in one of the earliest datasets proved to be incomplete when data was extracted from this format. A more serious problem though was found with the data dictionaries that gave the names of columns, explanations of their use and keys to encoded values.

The data dictionaries had themselves been migrated in 1991-2 and data had been lost from them, the explanations provided for some columns having been cut short. In these and other cases column descriptions were duplicated, even though the columns clearly contained different data. This was not the only problem, since the dictionaries also contained unexplained abbreviations and unexplained encoding that made it impossible to define the meaning of each column precisely. It would normally be possible to overcome these deficiencies by referring to the paper documentation and copies of the original survey forms. For the very earliest 1975-9 datasets (and some later years), these documents had apparently not survived. Since other datasets were more fully documented, and in the interest of preserving as long a time series as possible, it was decided to engage in some 'digital archaeology' to recover the early metadata.

With the help of two County record offices and a few schools, some copies of completed survey forms were located, along with instructions for completing the forms. The completed forms were matched up to the corresponding digital records, and the meanings of the columns became clear. The annual volumes of education statistics in which the results of the 1975-9 schools census were originally published gave further help, by explaining some of the mysterious abbreviations and coding schemes used in the survey. The catalogues for these datasets were brought up to the normal high level of completeness, in this case through an unusually thorough process of research. Routine cataloguing is normally more straightforward, though the level of skill and experience required to capture all the information needed to make datasets readily usable should not be underestimated.

A Transatlantic View

In the United States, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) [7] has been archiving Government datasets for a much longer period, and in 2003 introduced the Access to Archival Databases (AAD) [8] Programme to allow on-line browsing of selected datasets through the Web. Some of the most popular of these datasets are derived from military sources. Casualty lists are available from the Vietnam War and other conflicts going back to the Second World War, the earlier records having originated on punched cards. These and other military records are open for public inspection, and generate large volumes of inquiries.

It is often forgotten that punched cards were in use for recording data from the year 1901, long before the computer era, and that cards continued to be used as a storage medium for a long time after the introduction of magnetic tape and disc media. Most of the early card records have been lost, but in a few cases they were considered valuable enough to be preserved and eventually transferred to magnetic media. The time horizon for digital records is farther back than is generally realised.

Punched cards from a later period are still occasionally received by NARA, who have a card reader hooked up to a PC to transfer them to disc. The PC software includes a card reader driver, once a fundamental part of every mainframe operating system and now an exotic novelty in the modern world. A similar facility is available in the UK.

The Future

The next step for the National Archives is the preservation of the more diverse digital data that is now produced by Government departments and agencies. The traditional preservation of printed text on paper is to be progressively replaced by preservation of the digital source files. A Digital Archive has been set up for this purpose, based on the same principles as the national dataset archive, and taking advantage of the latest generation of storage technology. Secure storage of closed data is again an important requirement. The first records to be received are from temporary bodies such as public inquiries, since these come to the National Archives as soon as the body is disbanded, without the usual intermediate period of storage at a Government agency. These records [9] are in a wide range of formats, including those produced by current office and graphics software products, but also including sound and video recordings and even virtual reality models. For the present, records are being stored in their original formats, and are made available only to on-site visitors to the National Archives at Kew. The presentation of these diverse records to Web users is a subject for future development.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Kevin Ashley and the NDAD team at ULCC.

References

- University of London Computer Centre Web site http://www.ulcc.ac.uk/

- The National Digital Archive of Datasets Web site http://ndad.ulcc.ac.uk/

- The PRO's Acquisition and Disposition Policies http://www.pro.gov.uk/recordsmanagement/acquisition/

- DocumentsOnline http://www.documentsonline.nationalarchives.gov.uk//

- Access to Archives http://www.a2a.org.uk/

- Peter Garrod, "The Schools' Census and Digital Archaeology", in Digital Resources for the Humanities 2001-2002: An Edited Selection of Papers, ed. Jean Anderson, Alastair Dunning and Michael Fraser (London: Office for Humanities Communication, 2003)

- The National Archives and Records Administration http://www.archives.gov/

- The Access to Archival Databases (AAD) System http://www.archives.gov/aad/

- Public Record Office: Digital Preservation http://www.pro.gov.uk/about/preservation/digital/holdings/default.htm