New Schemas for Mapping Pedagogies and Technologies

In this article I want to reflect on the rhetoric of ‘Web 2.0’ and its potential versus actual impact. I want to suggest that we need to do more than look at how social networking technologies are being used generally as an indicator of their potential impact on education, arguing instead that we need to rethink what are the fundamental characteristics of learning and then see how social networking can be harnessed to maximise these characteristics to best effect. I will further argue that the current complexity of the digital environment requires us to develop ‘schema’ or approaches to thinking about how we can best harness the benefits these new technologies confer.

The Tension between Web 2.0 and Education

So my primary interest is to focus on the educational aspects of new technologies and in particular what might be appropriate ‘schema’ for describing the ways in which technologies are being used.

There is an inherent tension between the rhetoric of Web 2.0 and current educational practices. For example, today’s digital environment is characterised by speed and immediacy; the ability to access a vast amount of information at the click of a mouse, coupled with multiple communication channels and social networks. This seems contradictory to traditional notions of education; the need to reflect, to build cumulatively on existing knowledge and develop individual understanding over time. Just as there has been a backlash against ‘fast food’ with the ‘slow food’ movement, some are arguing for the need to a return to ‘slow learning’ as a counter to the speed and immediacy that digital learning appears to offer.

Similarly a key characteristic of Web 2.0 is user participation – the ‘wisdom of the crowds’, the ‘architecture of participation’ – mash-ups, remixing and co-construction are fundamental and widespread practices in Web 2.0. In contrast, despite the general increase in group-collaboration in recent years, fundamentally educational systems revolve around individual testing – evidencing of attainment of a level of knowledge and understanding against a set of pre-defined criteria. Even where group work is encouraged, more often than not there are strategies to ensure recognition of individual contribution to some extent.

Ever since the advent of the Internet and access to information, many have argued for a need for changes in assessment practices – ‘if information is abundantly available, surely assessment processes which focus primarily on knowledge recall are inappropriate?’ Similarly whereas in a Web 2.0 world, cut and pasting, combining different sources, and editing other peoples’ work (through wikis for example) is encouraged and is indeed fundamental to the nature of how Web 2.0 works, such practices in the current educational climate constitute plagiarism.

Even the nature of academic referencing is being challenged in the fluid way in which ideas are developed, transformed and transferred through the blogosphere. Yes there is an inherent practice of cross-referencing sources in the blogosphere, however the speed with which ideas are taken up and transferred across blogs is such that it is almost impossible to identify ‘a source’ for many ideas. My own use of a blog has caused me to reflect on and rethink the nature of academic discourse and the relationship between how I develop and convey my ideas through traditional media such as journal publications and conference proceedings compared with my use of blogs. I have been surprised at how liberating and useful blogging has been, as a ‘stream of consciousness’ of the development of my ideas, through being part of an evolving collective of other thinking in the community and increasingly as my main reflective research journal and repository of ideas and resources.

The ‘wisdom of the crowds’ notion argues that user-generated content and mass participation enable new ways of co-constructing ideas. Education is still predicated on a striated structure – crudely put with ‘teacher’ as ‘privileged expert’, this is despite the rise in pedagogies such as social constructivism, which emphasise the need for co-construction of knowledge and support a more learner-centred approach. Traditionally education and the way in which it is taught, is divided into subject fields with knowledge on the whole static and unchanging. This model has been increasingly challenged in the last few decades as subject domains fragment and diversify and as knowledge seems to expand exponentially. It is no longer possible for any individual to be an expert in their field, with an understanding of the full scope of their domain. Web 2.0 by its nature copes seamlessly with a complex and changing knowledge domain; fundamental to Web 2.0 practice is that no one individual is expert, rather they are part of a social network of others; the power of the Web enables knowledge to be co-constructed and hence continually change as needed.

Even where the pedagogy is learner-centred, current educational systems are not – administrative processes and assessment practice remain firmly bound to hierarchical, differentiated educational structures. For those espousing more radical and innovative pedagogical approaches, Web 2.0 seems to have much to offer through equity of participation and mutual negotiation – the question is ‘will simply letting "Web 2.0" loose on education be enough to bring about such changes or is something more needed’? Will the changes in social practice we have seen generally through adoption of Web 2.0 happen automatically or is there something fundamentally different about education?

Whichever aspects you look at there appears to be an irresolvable tension between current educational practice which is essentially individualistic and objective, and the philosophies inherent in Web 2.0 – namely social and subjective. So there are huge tensions between the potential of Web 2.0 and our current educational systems.

Realigning New Technologies to Pedagogy

I have a fear that because the technologies are so exciting and beguiling that we are seeing a technologically deterministic drive, rather than one based on sound pedagogies. However I will also show that there has never been a closer alignment between the current practices of Web 2.0 technologies and what is put forward as good pedagogy – what we need are means to realise and harness this match. Therefore in order to counter a primarily technological drive, where, educationally, use is shaped by the tools, rather than the other way round, I want to put forward some ideas for matching the affordances of the tools to what they offer for learning. In particular I want to suggest two new schema/approaches, which we might adopt to make sense of this and harness the potential of new technologies.

I want to consider this from a number of perspectives. Firstly, looking at existing learning theories and reflecting on how they align with Web 2.0 practices through use of a pedagogical framework against which to map tools. Secondly, I want to suggest some ideas to help us to map Web 2.0 better to the kinds of pedagogical practices we want to promote, through use of a matrix mapping key learning principles to the pedagogies they promote. These two different schema or ways of thinking are not intended to be definitive but rather are put forward as suggestions of how we can begin to think differently about how to evaluate and apply the existing affordances the new technologies offer.

To demonstrate the parallels between current technology developments and pedagogy I want to draw on some work we did a few years ago [1]. We undertook a review of learning theories focusing on how the specific characteristics of each relates to the affordances of different digital media; from theories which are more individual and cognitively focused through to those where the emphasis is on social and situative learning. For example ‘behaviourist theories’ (such as instructivism) where the focus is on stimulus-response and observable learning outcomes maps well to technologies which enable trial and error and adaptive responses – such as e-assessment tools. In contrast, a range of asynchronous and synchronous communication tools provide ample opportunities for dialogue, a key element to pedagogies based on socio-constructivist principles, where the emphasis is on co-construction of knowledge.

| Theories | Main focus | Map to technologies |

| Behaviourism |

|

|

| Cognitive constructivism |

|

|

| Social constructivism |

|

|

| Situated learning |

|

|

Table 1: Technology affordances mapped to different learning theories

Table 1 includes an extract of some of the theories considered in that chapter, their main pedagogical focus (for example, trial-and-error learning or learning through social interactions), and a suggested list of technological affordances which might best support these characteristics. Recent thinking in learning theory has shifted to emphasise the benefit of social and situated learning as opposed to behaviourist, outcomes-based, individual learning. What is striking is that a mapping to the technologies shows that recent trends in the use of technologies, the shift from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 echoes this; Web 2.0 tools very much emphasise the collective and the network. In a related chapter [2] I compared tools pre-2005 with those post-2005 against their key functionality. These were divided into 11 types:

- text and data manipulation;

- presentation and dissemination;

- data analysis;

- information seeking and handling;

- storing and managing information;

- personal management;

- project management;

- communication;

- visualisation and brainstorming;

- guidance and support; and

- evaluation and assessment.

The post-2005 tools very much emphasise the fundamental shift with Web 2.0 from information to communication:

It is significant that many of the post 2005 tools are available as free, online services. What is also noticeable about these new tools is that many are multifaceted in nature. Their use in combination has led to a new paucity in the system, information can be transmitted seamlessly between systems and functionality created in one tool can be embedded or made available in another. For example the ‘embed’ function enables slideshare presentations or Youtube videos to be incorporated into blogs and run in situ in that environment. This enables users to create their own personal environment and to consume information at a location and in a format they choose/control. The emphasis on the social and collaborative characteristics of these new tools is very prominent, as is the shift from desktop tools to Web services - emphasising the assumption that there is near-ubiquitous access to the Internet.

Arguably then there has never been a better alignment of current thinking in terms of good pedagogy – i.e. emphasising the social and situated nature of learning, rather than a focus on knowledge recall with current practices in the use of technologies – i.e. user-generated content, user-added value and aggregated network effects. Despite this, the impact of Web 2.0 on education has been less dramatic than its impact on other spheres of society – use for social purposes, supporting niche communities, collective political action, amateur journalism and social commentary. The same lag was evident with the impact of Web 1.0 tools: whereas businesses transformed their systems and practices through embracing the potential of technologies, educational systems did not. This difference is due to a complex set of factors – technological, organisational and pedagogical. Educational systems are slow to change; the practice and process of teaching and learning are embedded in these systems. Take, for example, assessment – the primary model in place is still one based on summative, individual assessment; although formative and more collaborative assessment is possible, it is more difficult in the current educational infrastructure. There are cultural issues as well, not least the need for a changing mindset of teachers in terms of their role. Therefore, I want to suggest that we need new ways of thinking about how to map different pedagogies to the use of tools. I offer two examples; one based on a framework highlighting different dimensions of learning which can be used to consider how to use different tools in specific contexts. The second example helps to articulate particular principles for learning and then map them against four overarching features of learning.

A Pedagogical Framework for Mapping Tools in Use

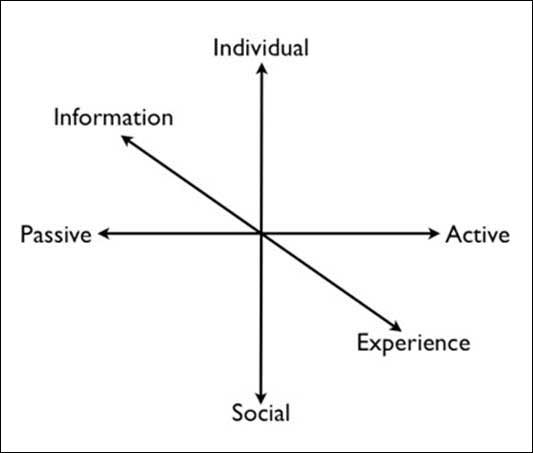

The first example I want to talk about follows on from the review of learning theories outlined above. For each learning theory we distilled out what were the key characteristics that particular theory promoted [1]. We argued that the different theories fore-grounded different aspects of these characteristics and showed this by mapping the theories against the framework. The framework has three dimensions (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Pedagogy framework for mapping ‘tools-in-use’

We argued that any particular instance of learning lies somewhere along a combination of the three dimensions shown in the figure. The first is the dimension of learning on one’s own, individually through to learning socially. The second dimension is learning through information versus learning through experience. The third dimension is learning passively versus actively. (Note that passive is not meant to be negative in this context – immersive language or music learning is a good example). The framework can be used as a means of mapping tools in use. For example consider two different uses of a blog; as a reflective diary or as a class-based, collective resource repository. This emphasises that using a blog as a reflective diary is primarily individual, active and experience-based; whereas a class blog is more social, still active but now primarily information-based. An e-portfolio used as part of a nurse-practitioner’s course as evidence of the students’ work-based experience, would be individual, active and experience-based. Collaborative construction of a project report on a review of the literature would be active, social and probably mid-way between information and experience. Of course any one individual using this schema would map particular instances differently, depending on their interpretation of the framework and the context of use of the tools; the point is this framework provides a useful schema to think about tools in use and how they map to different characteristics of learning.

Mapping Pedagogical Principles

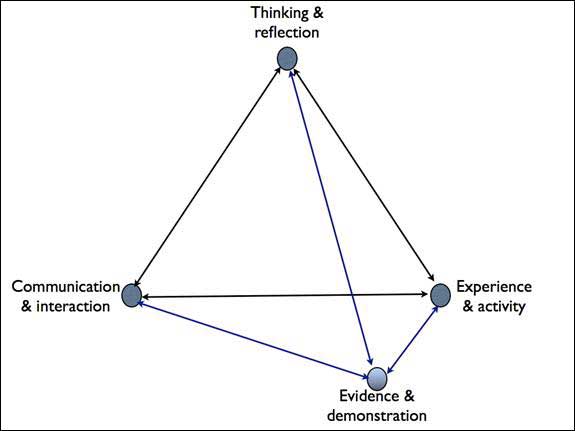

The second example focuses not so much on the tools and how they are being used, but on how the particular principles of a learning situation maps to characteristics of learning. With this approach the learning principles for a particular learning situation are mapped against four key characteristics of learning [3][4], i.e that learning in any situation is some combination of learning through:

- thinking and reflection

- conversation and interaction

- experience and activity

- evidence and demonstration.

Figure 2: A framework of learning characteristics

Figure 2 illustrates these learning characteristics. This can then be used as the basis against which to benchmark pedagogical principles for any particular learning scenario. A simple example of how this can be used is shown in Table 2. So, for example, a learning activity that enabled learners to reflect on their experience, say for example, in a work-based learning context – would map to ‘thinking and reflection’ and ‘evidence and demonstration’. In contrast, an activity that supported collaboration would map to the first three characteristics.

| Principles | Learning characteristic | |||

| Thinking & reflection | Conversation & interaction | Experience & activity | Evidence & demonstration | |

| Reflect on experience and show understanding | √ | √ | ||

| Frequent interactive exercises and feedback | √ | √ | √ | |

| Provides support for independent learning | √ | √ | √ | |

| Supports collaborative activities | √ | √ | √ | |

Table 2: A matrix of principles against the learning characteristics they promote

In the Open University, we are engaged in two large-scale e-learning initiatives that provide useful case studies against which to test this matrix concept; SocialLearn and Openlearn. Social:Learn is a relatively new initiative attempting to apply the best of Web 2.0 principles to an educational context [5][6]. The aim is to provide an enabling learning architecture along with a series of exemplar learning applications that demonstrate how Web 2.0 principles can be applied in an educational context. The question driving SocialLearn is ‘if we were to start a new university from scratch, harnessing the very best of new technologies – what would it look like?’ In contrast, OpenLearn began as an initiative more from a content perspective. Funded by the Hewlitt Foundation, the OpenLearn Project is making ca. 10% of the OU’s educational resource freely available as Open Educational Resources (OERs). The site has been built using the Moodle platform, and in addition to the OERs a range of social tools are also provided to encourage discussion and collaboration among users [7].

Tables 3 and 4 show the matrix mapped to the principles derived for SocialLearn and OpenLearn. They provide a useful visualisation of how the principles map across the four aspects of pedagogy outlined in Figure 2. Such matrices can be used with end-users to get them to reverse-engineer the pedagogical assumptions inherent in the design of a particular learning intervention or alternatively can also be used as the basis for developing new learning applications at the design stage.

| Mapping of pedagogies to Social:Learn principles | Thinking and reflection | Experience and activity | Conversation and interaction | Evidence and demonstration |

| Supports a range of pedagogies and styles | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Formalises the informal | √ | |||

| Informalises the formal | √ | |||

| Is built on relationships between people | √ | |||

| Harnesses the Internet (social scale, user generated content, etc.) | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Aggregates learning events, resources, and opportunities | √ | |||

| Provides structures and scaffolds for the learning process | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Uses metaphors and simple approaches to impart pedagogy | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Encourages a range of participation | √ | |||

| Evidence via range of informal and formal assessment mechanisms | √ | |||

| Lifelong support across different learning goals | √ | √ | ||

| Provides access to expertise | √ | |||

| Supports collaborative elements | √ | |||

| Helps surface incidental learning | √ | √ | ||

| Wraps learning around an individual’s interests | √ | √ | √ | |

| Enables learner control and learner responsibility | √ | √ | ||

| Allows users to build reputation in the system | √ | √ | ||

| Encourages legitimate peripheral participation | √ | |||

| Encourages learning through observation | √ | |||

| Supports different subject areas and styles | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Encourages mentorship | √ | |||

| Mapping of pedagogies to Social:Learn principles | Thinking and reflection | Experience and activity | Conversation and interaction | Evidence and demonstration |

Table 3: Application of the pedagogy framework to SocialLearn

| Mapping of pedagogies to OpenLearn principles | Thinking & reflection | Experience & activity | Conversation & interaction | Evidence & demonstration |

| Search and use of a pool of quality-assured, open access content | √ | √ | ||

| Provides support for learners adopting independent learning | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Opportunity for reuse and repurposing | √ | √ | ||

| Lifelong support across different learning goals | √ | |||

| Provides students with access to ‘captured’ expertise in content | √ | |||

| Includes a variety of activities and interactivity | √ | √ | ||

| Offers opportunities for in-built formative feedback | √ | √ | ||

| Potential for teachers to adapt and embed in their teaching | √ | √ | √ | |

| Provides conduit for sharing learning designs | √ | √ | √ | |

| Supported through informal social networking tools | √ | |||

| Knowledge mapping and visualisation to aid understanding | √ | √ | ||

| Opportunities for presence indicators to support different communities | √ | |||

| Dialogue through tailored content-focused forums | √ | √ | √ | |

| Channel from informal to formal learning | √ | |||

| Opportunities for student-generated content | √ | √ | ||

| Good pedagogical design embedded in content | √ | |||

| Personalisation through discrete stand-alone units of learning | √ | √ | ||

| Aggregates learning opportunities, resources & opportunities | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Mapping of pedagogies to OpenLearn principles | Thinking & reflection | Experience & activity | Conversation & interaction | Evidence & demonstration |

Table 4: Application of the pedagogy framework to OpenLearn

Feedback from SocialLearn workshops where this matrix has been used suggests that it is useful in two respects. Firstly, revisiting the original list of pedagogical principles developed for SocialLearn in January 2008 demonstrated that they are proving to be a robust list; they are still valid and hence do capture the essence of what we are trying to do with SocialLearn. Secondly, exposing the principles to others in the workshops helped exemplify what SocialLearn was about and importantly what it is trying to achieve pedagogically. In addition, the participants were able to add to the list, to suggest new additions to the principles in light of current developments in the project; so the list is becoming a dynamic, evolving set of principles, which can be added to as SocialLearn develops and as the ideas become instantiated in the learning platform and associated applications. Now that we have developed an approach that appears to be of value, this will be used as the basis for gathering users’ views on the educational aspects of SocialLearn at future events and also as a basis of thinking through new learning applications at the design stage.

Implications

Having suggested some ways of thinking about how better to harness Web 2.0 in education and make sense of the complex, dynamic digital environment in which learning and teaching now takes place, I wanted to conclude by broadening the arguments and reflecting on the implications beyond the microcosm of learning and teaching practice to educational institutions. I will argue that these changes are having, and will continue to have, profound implications for individual roles as well as for organisational structures and processes.

Blogs act as valuable barometers of change, and so to illustrate the above I want to draw on some recent discussions in the blogosphere, which to my mind exemplify some of the core issues. It is evident that the new technologies now enable individuals to personalise the environment in which they work or learn, appropriating a range of tools to meet their interests and needs. The term ‘Personal Learning Environments’ (PLEs) has been in circulation for a number of years now and although exact interpretations of what a PLE is vary, crudely they are offered by many as an alternative to institutionally controlled Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs). Martin Weller has written a lot about this and has blogged about what he sees as his current working environment or ‘PLE’, namely a mixture of tools to meet the different aspects of his job [8]. What is interesting with Martin’s picture is that, although the details will vary, such a personal working environment and mixture of institutional and self-selected tools are increasingly becoming the norm. Research looking at how students are appropriating technologies points to similar changes in practice: students are mixing and matching different tools to meet their own personal needs and preferences, not just relying on institutionally provided tools and indeed in some instances shunning them in favour of their own personal tools [9].

In November 2007 Martin sparked a contentious debate in the blogosphere with his post ‘The VLE/LMS is dead!’ touching on some of the issues relating to changes in the way staff and students are using tools [10]. In it Martin argued that the plethora of freely available, and often functionally better, tools now available is challenging the notion of an institutionally developed and controlled VLE. The discussion that ensued in the blogosphere covered the range of issues associated with the tensions inherent in this dichotomy.

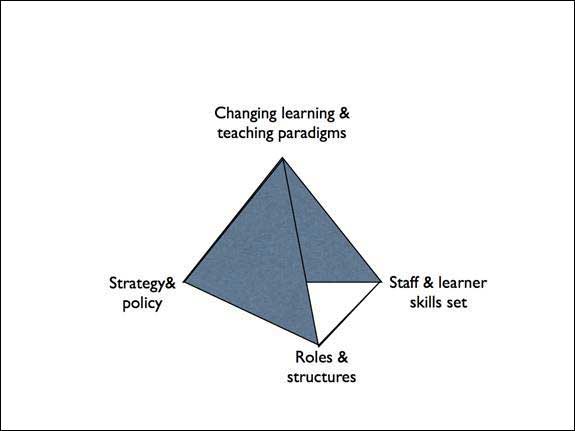

So clearly there is a tension between personalised tools verses institutional tools, between having integrated institutional systems and loosely coupled systems, and the issue of what we should control and what students should control. The implications are profound, for institutional structures and processes, for individual roles and identities, for the way in which we view learning and teaching (Figure 2).

Figure 3: The impact of new technologies on organisations, individuals and practices

I have put forward some models here that provide a starting point to enable us to take a more constructive and focused approach to thinking about new tools and their implications for learning. However we need new ways of thinking, not just to map tools to pedagogy, but to think about institutional structures and processes, to map changing roles, and to guide new thinking on strategic policies to guide the direction of change. We are only at the start of unpacking what this will mean for the future of all aspects of education. If we constructively embrace the potential of new technologies, I believe they have much to offer in terms of providing more engaging, personalised learning opportunities for our students; we ignore them at our peril.

References

- Conole, G., Dyke, M., Oliver, M. and Seale, J. (2004). ‘Mapping pedagogy and tools for effective learning design’, Computers and Education.Volume 43, Issues 1-2, August-September 2004, Pages 17-33.

- Conole, G. (submitted). ‘Stepping over the edge: the implications of new technologies for education’, in M. Lee and C. McLoughlin (Eds), Web 2.0-Based E-Learning: Applying Social Informatics for Tertiary Teaching’, Ideas publications.

- Dyke, M., Conole, G., Ravenscroft, A. and de Freitas, S. (2007). ‘Learning theories and their application to e-learning’, in G. Conole and M. Oliver (ed), Contemporary perspectives in e-learning research: themes, methods and impact on practice’, part of the Open and Distance Learning Series, F. Lockwood, (ed), RoutledgeFalmer.

- See also e4innovation http://www.e4innovation.com/ for a background to the development of these ideas.

- Walton, A., Weller, M., and Conole, G. (2008). Social:Learn – Widening participation and the sustainability of higher education, Eden Conference workshop, June 2008, Lisbon.

- Social:Learn Web site: http://sociallearn.open.ac.uk/

- OpenLearn Web site: http://openlearn.open.ac.uk

- Weller, M. (2007). My personal work/leisure/learning environment, blog post, 6 December 2007 http://nogoodreason.typepad.co.uk/no_good_reason/2007/12/my-personal-wor.html

- Conole, G., De Laat, M., Dillon, T. and Darby, J. (2008). ‘Disruptive technologies’, ‘pedagogical innovation’: What’s new? Findings from an in-depth study of students’ use and perception of technology’, Computers and Education, Volume 50, Issue 2, February 2008, Pages 511-524.

- Weller, M. (2007). The VLE/LMS is dead, blog post, 8/11/07, http://nogoodreason.typepad.co.uk/no_good_reason/2007/11/the-vlelms-is-d.html