OAI-ORE, PRESERV2 and Digital Preservation

The new framework for the description and exchange of aggregations of Web resources, OAI-ORE, had its European release in April 2008 [1]. Amongst its practical uses, OAI-ORE has a role to play in digital preservation and continued access to files. This article describes the basic outline of the framework and how it can support the PRESERV2 project digital preservation model of provision of preservation services and interoperability for digital repositories. The PRESERV approach recognises that effective preservation is founded on three fundamental actions on data: copy, move and monitor. This includes the copying and movement of data between different repositories which is where OAI-ORE has a role to play. OAI-ORE also plays a part in interoperability to ensure that repositories and other tools and services can communicate and share information and data. In this way the project is creating and testing a flexible framework for an emerging range of services and tools, to ensure support for long-term access to the data deposited in repositories.

CRIG Repository Developers' Challenge

The Open Repositories conference in April 2008 (OR08) [2] saw developers in competition for the prestigious Repository Developers' Challenge award (supported by the JISC CRIG (Common Repository Interface Group) [3]. The focus of the contest was to 'get rapid cross-platform international development' by developers working in small groups 'to demonstrate how to achieve real-life, user-relevant scenarios and services' [4]. There was just one rule for entrants: the prototype created had to utilise two different repository platforms.

Figure 1: CRIG diagram

Knowing that the emerging OAI-ORE framework [5] is likely to form a key component of repository development, the ORA (Oxford institutional repository, Oxford University Research Archive) [6] software engineer, Ben O'Steen had implemented OAI-ORE resource maps (a fundamental part of the framework) into ORA some time before OR08. Then at the conference, close collaboration in the developer's lounge between Ben, Dave Tarrant and Tim Brody, colleagues from the JISC-funded PRESERV2 project team [7] resulted in a live demonstration of interoperability between two separate live repositories built on different platforms. Bluntly, they took an entire ePrints repository and deposited it, metadata, content and all, into Fedora. They then took a Fedora repository and deposited it in ePrints. The results were there for all to see and demonstrated that digital objects can be moved easily between repositories running different software platforms. Most importantly, the objects were useable, for example for search, display and access in their new homes with the functionality and interface of the opposite repository. This turned out to be the winning entry in the JISC-CRIG challenge [8]. The JISC PRESERV2 project team had demonstrated one of the first implementations and actual usage of the OAI-ORE standard in two live production repositories at the OR08 conference. Ben, Dave and Tim had titled their challenge entry 'Data Mining with ORE,' [9] and it was a particularly timely and groundbreaking demonstration because it took place the day before the European release of ORE at the same conference.

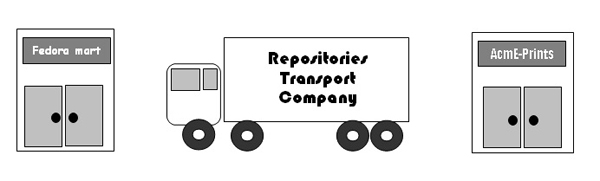

But why would anyone want to do this, especially when OAI-PMH is working well and allows for metadata sharing? Transferring a collection in this way using OAI-ORE is a satisfying technical accomplishment, but there are real-life benefits for repositories of this new framework. OAI-ORE, as the underlying method to achieve this transfer, provides digital content managers with a new tool for repository data management, for making their content more transportable and therefore more useable and reusable. Importantly, OAI-ORE provides a mechanism to assist with digital preservation and continued access to digital content.

Figure 2: Copying content from one repository to another

A Brief Description of OAI-ORE

Very simply, OAI-ORE permits easier dissemination of digital content. It is a completely separate standard to OAI-PMH and 'neither extends nor replaces it.' OAI-PMH has as its basic tenet 'a mechanism for harvesting records containing metadata' from one repository for reuse elsewhere [10]. This has so far been adequate and supported the openness of repositories. However, an extension of both the uses of repositories and of types of content now requires more comprehensive methods for sharing content, with more capability in terms of what is harvested and how it is reused. Also, there are problems of interoperability with OAI-PMH which the ORE specification aims to address [11]. Instead of focusing on the constraining concept of bulk collections comprising single files held in repositories with only the metadata available for harvesting (you can have the recipe but not the ingredients), OAI-ORE targets the resources themselves, with Web servers acting as data locators wherever that location happens to be. In short, where OAI-PMH focuses on metadata, OAI-ORE focuses on content (you can have the recipe, the ingredients and the cake).

The ORE specification provides a model with which we can describe curated digital content, and details a number of ways to express this description. One common way is to describe it using RDF (Resource Description Framework). The ORE specification provides a vocabulary (an 'ontology' in RDF nomenclature) with which this can be done in a way that external agents can understand.

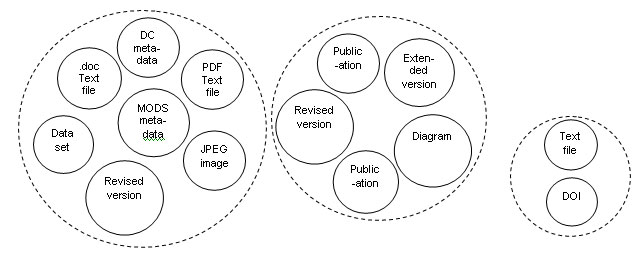

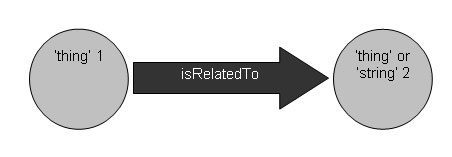

Digital objects range from an elementary item comprising no more than a small text file with its accompanying metadata, to something much more complex consisting of multiple components. These latter object types can be described as complex or compound objects. In ORE terminology, the elements that make up a compound object are grouped into an aggregation. The aggregation does not have a defined structure: it is a theoretical concept and can be described as a 'bag' of resources. The elements that make up the aggregation (aggregated resources) can be treated as separate entities if required. An element can be a 'thing' (such as a text file or 'http://ox.ac.uk/people/jsmith08') or a 'string' (such as 'John Smith' which is just a string of characters). Every 'thing' has a name (or URI – Uniform Resource Identifier) which can point to its location and if appropriate, for example if it is a URL, can resolve.

Figure 3: Aggregated resources

There are endless examples of what might comprise an aggregation, for example, one resource available in multiple formats, a resource plus its supplementary material such as data, different versions of one resource, a book comprising a collection of separate images of its pages [12] or a number of articles that form an issue of a journal. However, an aggregated resource need not be as complex as this: it might comprise a single text file plus some identifiers and other basic data. Aggregations are generally used for binding together portions of content that are repository common currency (such as publications, images etc). RDF is particularly useful for binding together content that might describe the context of the item and which are not in themselves digital objects. They might include objects (or more correctly representations) such as a person, a research group or a funding agency [13].

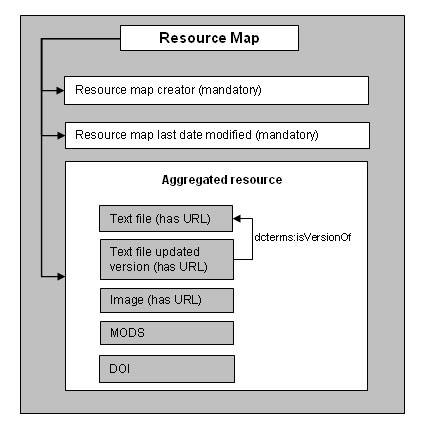

An OAI-ORE resource map describes an aggregated resource. The fact that OAI-ORE makes aggregations machine-readable opens up a number of possible applications and possibilities for automation. Lagoze and van der Sompel et al [14] suggest that this will permit applications such as those enabling Web browsers to offer advanced navigation using the aggregation information, to 'provide the foundation for advanced scholarly communication systems that allow the flexible re-use and refactoring of rich scholarly artifacts and their components,' and also to assist in preservation (see below).

A resource map can only describe a single aggregation. However, one element within an aggregated resource can be grouped 'within more than one aggregation, each described by a resource map [15].' The resource map might offer information about the types of resources and define the relationships between them. The resource map might use RDF in XML. The relationships between the separate elements within the aggregation can be described within the resource map using terms such as 'isVersionOf' or 'isReferencedBy' or 'isPartOf' [16]. Such relationships (or predicates) incorporate the RDF 'triple' method and describe interrelationships semantically. This fits with the Semantic Web.

Figure 4: RDF Triple

Using the ORE specification provides a means of packaging up these related objects, including the semantic description of the relationships, using a common agreed method. The package and its content are not necessarily fixed as prescribed by some other methods of packaging or wrappers – the content can be reused in other aggregations. As stated above, the aggregation is only a concept, so although the boundaries describing an aggregation can be set, aggregations allow different digital items to be grouped together in such a way that each individual component can be regrouped, discovered and reused in its own right.

Figure 5: Resource Map

Using the OAI-ORE specification means that it is possible to copy these descriptions (resource maps) easily to another location. The copy will include the relationships between the elements and the element names/locations by way of the URIs (for example, URLs). If the new location wishes to obtain the actual content (for example, the text file) it can, via the locator (perhaps a URL) given in the resource map.

Repository software can be extended so that it understands ORE resource maps and can therefore recreate the digital object, retaining all relationships in its new location, even though the second repository might have different architecture (cf. 'Data Mining with ORE' at the OR08 Repository Challenge). There are a number of different repository software platforms in use (such as EPrints, DSpace and Fedora) which until now have been incompatible in terms of architecture. OAI-ORE means that there can now be lossless transfer of objects between different platforms, thereby making them interoperable.

What Does OAI-ORE Mean for Digital Preservation?

The PRESERV2 Project is exploring how OAI-ORE can be used for digital preservation activities. The PRESERV2 model works on the principle of using modular preservation services. Each service might cover a different aspect of the preservation process and can be the responsibility of shared or distributed parties. The PRESERV2 model takes as its starting point The National Archives' (TNA) 'seamless flow' approach of the three stages of preservation:

- format identification and characterisation (i.e. which format?)

- preservation planning and technology watch (format risk and implications)

- preservation action, migration etc. (i.e. what to do with the format)

The PRESERV2 premise is that eventually preservation services will be employed for all of these stages. The project will produce an exemplar characterisation service using the PRONOM [17] technical registry and DROID (Digital Record Object Identification) services from TNA [18].

A first principle for PRESERV2 was to be able to replicate an entire repository, regardless of the platform it uses. The copy could be in a large-scale open storage service or use Web storage. Preservation services might then be implemented at this new location. The ORE specification allows for incremental updates and for changes and updates to digital content to be recognised by a secondary repository location. OAI-ORE enables complete lossless archive replication and therefore provides the means to replicate the digital objects, including all their metadata, their complex relationships and their history. Inclusion of such object history data is an important part of digital preservation as it records the provenance of the item. Any record of preservation actions held in the metadata can, using OAI-ORE, be retained with the compound document. For example, a document could be updated and the modified version added to the repository along with the date that the modifications were made. The new file can be included in the aggregation with its semantic description showing that it is a new version, together with additional data about the file. The resource map will include all this detail together with the location of the new and old files.

It is important to remember that the RDF description of the content, including the OAI-ORE resource map, is machine-readable. This assists preservation because an automated system is able to understand the structure of any items, including compound documents. As a result, providing policies and actions have been determined and set, a machine can ascertain the optimal procedure for taking preservation actions on that document, even if it is complex. The chosen actions should be defined by repository policy. For repository managers this helps to manage the activities required to preserve their digital content in a way that is achievable. Not only does it mean that decisions can generally have been made in advance and in agreement with relevant parties, they can then be acted on automatically as specified in the policy. The automated nature of the process means that it is scaleable. When considering the potential size of repositories and the wide-ranging mix of file formats that are likely to be held (and the volatility of some of those formats), automation is key for many aspects of repository management including digital preservation and curation.

When laying the PRESERV2 model on this scenario, repository services can be automatically activated as desired in compliance with policy, whatever the complexity of the digital object and whatever the size of the repository.

Use of OAI-ORE means that it is relatively easy to place copies of items in alternative locations. Put simply, working on the LOCKSS [19] principle, this means that there is more likelihood of the item surviving over time because more copies are in existence. Each location of the item may have its own preservation actions acting on the content. Such actions may be undertaken by services as described in the PRESERV2 model. Within a single repository or institution use of OAI-ORE means that copies of items can be easily stored as archival copies in distributed physical locations for preservation purposes. Not only is the file containing the content stored in different locations, but all the metadata that accompanies it can be retained with the item, meaning that the description, history, rights, technical details and other important information is linked to the content, making preservation, curation and future access much more straightforward. The richer picture of how digital objects relate to each other can also be retained and preserved.

Providing that the policy and technical set-up are properly implemented, RDF using vocabulary provided by OAI-ORE enables the selected content in say a subject (or other) repository to be copied without loss to an institutional repository, and also work with the second repository's functionality. Equally importantly, it allows content in the institutional repository to be copied into the subject repository. Admittedly, this is a somewhat simplistic view. There are factors that need resolving including version control, use of identifiers, moving compound items from a complex to a simpler system and so on. But in principle, this scenario offers vast potential for using, reusing and re-grouping material in different ways as well as acting as a safety net for continued access to items.

Conclusion

Enhancement of repository services has been furthered by the adoption of RDF together with the OAI-ORE specification and its manifestation by the PRESERV2 team's activities that won them success in the OR08 Developer's Challenge. In the ORE world, the focus moves away from metadata and on to content, especially when dealing with the complexities of digital objects, resulting in better services for users. In addition to its other benefits, implementing OAI-ORE provides one tool in the repository managers' toolkit to help tackle the monumental problem of digital preservation, curation and continued access. The PRESERV2 model of preservation services provides one option for preservation activities to be undertaken in a way that is realistic and removes the prospect of a single gargantuan task to be undertaken at source. Coupled with OAI-ORE, such services can be applied to repository content of mixed complexity where details such as provenance and relationships are retained. Being able to invoke automated actions on digital objects in a way that is manageable and scaleable, and by enhancing object mobility so that more copies of those digital items can be stored in distributed locations, offers the increased likelihood that the objects will not only survive, but will remain accessible and by extension, usable. Once these preservation services and actions are realised, the focus then moves to policy.

References

- Open Archives Initiative Announces U.K. Public Meeting on April 4, 2008 for European Release of Object Reuse and Exchange Specifications

http://www.openarchives.org/ore/documents/EUKickoffPressrelease.pdf and Open repositories 2008: OAI-ORE European Rollout Meeting

http://or08.ecs.soton.ac.uk/ore.html - Open Repositories 2008 (OR08) http://or08.ecs.soton.ac.uk/

- Common Repository Interface Group, set up to examine the boundaries between repositories and other systems

http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/repositories/digirep/index/CRIG - OR08: Developer Activities — The Repository Challenge http://or08.ecs.soton.ac.uk/developers.html

- Open Archives Initiative Protocol - Object Exchange and Reuse http://www.openarchives.org/ore/

- Oxford University Research Archive (ORA) http://ora.ouls.ox.ac.uk/

- Preserv: Inspiration and Provision of Preservation Services for Digital Repositories http://preserv.eprints.org/

- RepoChallenge – for details and videos of entries see: http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/repositories/digirep/index/CRIG_Repository_Challenge_at_OR08

- Mining for ORE, Dave Tarrant, Ben O'Steen and Tim Brody. Video http://blip.tv/file/866653

- Johnston, P., et al (2008). Open Archives Initiative object re-use and Exchange. ORE User Guide – Primer. 11 July 2008.

Beta release available at http://www.openarchives.org/ore/0.9/primer.html - Lagoze, C., Van der Sompel, H., Nelson, M.L., et al, (2008). Object re-use and exchange: a resource-centric approach

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/0804/0804.2273.pdf - See for example MS Oxford St John's College 17 Available at http://ora.ouls.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid%3Acf31eb38-06b3-426f-843c-32108c18bf5d

- A concept which forms the basis of the JISC-funded Building the Research Information Infrastructure (BRII) Project at the University of Oxford

- Open Archives Initiative object re-use and Exchange, (2008). ORE Specification and User Guide http://www.openarchives.org/ore/0.9/toc

- Lagoze, C., Van der Sompel, H., Nelson, M.L., et al, (2008). Object re-use and exchange: a resource-centric approach.

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/0804/0804.2273.pdf - See for example, DCMI terms at http://dublincore.org/documents/dcmi-terms/index.shtml

- PRONOM http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pronom/

- The National Archives of the United Kingdom http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

- Lots Of Copies Keep Stuff Safe http://www.lockss.org/lockss/Home