KAPTUR the Highlights: Exploring Research Data Management in the Visual Arts

Leigh Garrett, Marie-Therese Gramstadt, Carlos Silva and Anne Spalding describe the exploration of the importance and nature of research data in the visual arts and requirements for their appropriate curation and preservation.

KAPTUR (2011-13) [1], funded by Jisc and led by the Visual Arts Data Service, was a collaborative project involving four institutional partners: the Glasgow School of Arts; Goldsmiths, University of London; University for the Creative Arts; and the University of the Arts London. Research data have in recent years become regarded as a valuable institutional resource and their appropriate collection, curation, publication and preservation as essential. This has been driven by a number of internal and external forces, and all UK Research Councils now require it as a condition of funding [2]. As a result, a network of data repositories has emerged [3], some funded by research councils and others by institutions themselves. However, at the outset of the project, research data management practice within the visual arts appeared to operate rather ad hoc with none of the specialist arts institutions within the UK having either implemented research data management policies [4] or established research data management systems. KAPTUR sought to:

- investigate the nature of visual arts research data;

- make recommendations for its effective management;

- develop a model of best practice applicable to both specialist institutions and arts departments within multidisciplinary institutions; and

- apply, test and refine the model of best practice across the four institutional partner institutions.

This paper outlines the background and context of the project; explores the nature of visual arts research data; details the outcomes of the user and technical review; and describes the work which underwent within the partner institutions around policy formation and staff engagement.

Led by the Visual Arts Data Service (VADS), in collaboration with the Glasgow School of Art, Goldsmiths College, University of the Arts London and University for the Creative Arts, and funded by Jisc, KAPTUR [1] sought to ‘...discover, create and pilot a sectoral model of best practice in the management of research data in the [visual] arts.’ [5].

Recent years have witnessed an increasing recognition across the Higher Education sector that research data are a valuable resource and therefore its appropriate curation and preservation are essential. In addition, wider societal and political forces meant that research councils, teams and researchers were coming under increasing pressure to make publicly funded data freely available. As such the publication of research data was increasingly becoming a requirement of funding, for example the Arts and Humanities Research Council [6] and Medical Research Council [7]. Equally important was the need for increased data transparency, and to enable researchers to access existing datasets to test the validity and reliability of the data and associated research methods; to reinterpret the data; and to preserve the data for future scrutiny. In response, many universities, for example the University of Edinburgh, had established institutional research data management systems to support the deposit and preservation of research data, whilst others were in the process of piloting services, for example the University of Leicester, and establishing policies and procedures which actively support researchers to manage their data effectively, such as Canterbury Christ Church University and Northumbria University. In addition, many of the research councils themselves had established repositories, for example the UK Data Archive at the University of Essex, which curates research data in the social sciences and humanities, and the Natural Environment Research Council, which supports a network of data centres across its disciplinary areas.

However, given the emerging landscape, at the outset of the project it was clear that very little was known about the collection, curation and usage of research data in the visual arts: none of the specialist arts institutions had research data management policies or infrastructure in place and evidence collected at the time indicated that practice was at best, ad hoc, left to individual researchers and teams with limited support or guidance. Little work had been undertaken to understand the distinctive and varied nature of research data in the visual arts, and even less to understand how these data could be collected, curated, preserved and exploited, or their potential impact assessed.

By its very nature, research in the visual arts is highly complex and varied, often comprising a wide variety of outputs and formats which present researchers, repository managers and institutions with many discipline-specific difficulties. The methods and processes which generate this research are just as varied and complex. Research endeavour in the visual arts relies heavily on the physical artefact: sketchbooks, logbooks, journals, and workbooks. Alongside these data, a wide range of related project documentation and protocols are also created. While technology may offer considerable potential to support the safe storage and preservation of research and related data, and to enhance access, the highly distinctive nature of the visual arts and its research methods also present enormous technical problems with regard to formats, standards, roles and responsibilities, and policies.

Why Is Research Data Important in the Visual Arts?

With two powerful opposing forces at work: external pressures and enormous technical challenges, the first step was to articulate clearly why the collection, curation, publication and preservation of research data in the visual arts were so important. The following factors were identified:

- they satisfy funders’ requirements and demands for open access;

- they would help to demystify research methods and outputs, and the arts themselves;

- they are extremely time-consuming and therefore costly, and their lack of discoverability or loss are inefficient;

- they may have a significant application and value far beyond the cost of their collection with outcomes which could have gone unrecognised in the initial investigation;

- they would enable other researchers to test the reliability and validity of the data and method;

- open access to research data would support their reuse and facilitate new interpretations, thereby adding value to, and enhancing the impact of, the original data;

- the publication of data would enable their impact to be tracked more accurately;

- they would enable researchers and semantic web tools to make new links more easily between isolated and previously undiscoverable datasets;

- they would extend collaborative opportunities to create new research opportunities between researchers and teams working on similar and related datasets;

- they would enable researchers, departments and institutions to maximise the value of limited public funding in research, and to showcase and maximise the impact of the arts in the forthcoming Research Excellence Framework (REF).

On this basis the appropriate curation and management of research data in the visual arts is therefore not only desirable but essential. KAPTUR became reality.

What Are Research Data in the Visual Arts?

The first task was to explore the nature and scope of research data in the visual arts. The variety and complexity of research outputs in the visual arts is well documented through work undertaken by the Jisc-funded KULTUR (2007-09); KULTIVATE (2010-11) and eNova (2011) projects. As such, at the time of writing the KAPTUR proposal, the team hypothesised that the complexity of research data in the visual arts mirrored that found in the resulting outputs, and a cursory exploration revealed they take many forms both physical and virtual. However, on reflection, this was an innocent trivialisation of the issues requiring much greater exploration. The project team spent a considerable amount of time exploring the question: What are research data in the visual arts? The environmental analysis was quick to identify the initial problem, terminology. The term ‘research data’ is not understood by visual researchers or their institutions. This was overcome to a certain extent by describing what visual arts research data are, by using examples. Further on, the team did attempt a definition, however discussions were ongoing throughout the lifetime of the project. Looking in greater depth, the environmental analysis revealed that the nature of visual arts research data can be: tangible and intangible; digital and physical; heterogeneous and infinite; and complex and complicated [8].

Figure 1: Denise Wren, 21 small tiles used to demonstrate different saltglaze tests on stoneware, 1960s.

© Rosemary Wren/Crafts Study Centre 2004. Photo: David Westwood [further details][9]

Tangible and intangible, signifies that research data can be perceived by touch in the form of physical objects. For example, a sketchbook could be considered tangible research data; however the tacit knowledge which informed its creation may remain intangible. Tacit knowledge is particularly relevant to artistic practice and practice-led teaching, as one interviewee states ‘[artistic practice as research] probably involves a lot more gut instinct and intuition than would be permissible in a scientific experiment’. Depending on the research methodology, tacit knowledge may become explicit as part of the research output or it may need to be recorded through the research data; for example, through annotations, blog posts, or correspondence.

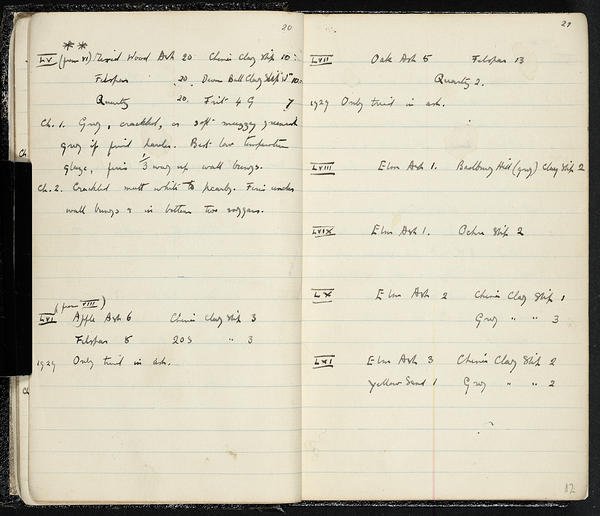

Figure 2: Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie, pages 20 and 21 of notes on biscuit glazes from notebook, 1930s.

Craft Study Centre.[further details][9]

Research data in the visual arts are considered as heterogeneous and infinite. Although other subject disciplines such as engineering have reported a wide variety of research data types and file formats [10], visual arts data are equally, if not more complex and diverse due to the nature of artistic research. Artistic research is relatively new compared to other disciplines, arising from the introduction of practice-based research degrees in the 1990s. As a result, research methodologies are borrowed or adapted from other disciplines, such as the social sciences, and often new and innovative research methods are developed. Gray and Delday describe the process of artistic research as, ‘...never a smooth and homogenous process but fluid, “wet” and folded, if not at times messy, fuzzy and tumultuous.’ (cited Mey 2010) [11]. Therefore the nature of visual arts research data is potentially infinite, never-ending. This is particularly the case with artistic research that is based on ‘the self’, as Gemmell and Giddens describe, ‘We are always in a state of becoming, always unfinished.’ (cited in Griffiths, 2010) [12]. One of the interviewees described their research process as much more of a continuum, without necessarily distinct or distinguished stages, but with ‘organisational moments’; at these points research data might be actualised as a natural part of the research process such as writing or ‘trials in the studio’. ‘Organisational moments’ might include: compiling materials for an exhibition; externally imposed information required for the institution or funders; making a grant application, writing a paper; institutional duties such as lectures, tutorials, or other learning and teaching events; or filing information. What became evident during the course of the environmental analysis was the enormous value visual arts researchers placed on their data and the requirement they had to share these data.

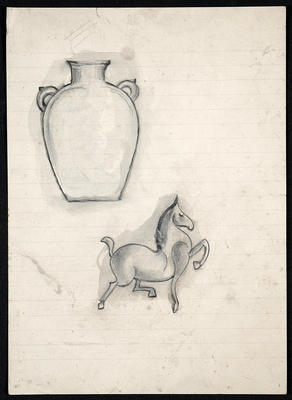

Figure 3: Lucie Rie, Sketches in pencil, ink, and watercolour, 1910s.

Lucie Rie Archive, Craft Study Centre [further details][9]

Complex and complicated, visual arts research data present many problems for the data curator, for example in terms of classifying materials, promoting discoverability and supporting access. One interviewee reported, ‘[my practice is] complex and complicated. [For my PhD] I thought I was doing sculpture, I ended up doing book design and photography and now I'm involved in performance practice more than anything else [...]’. This confirmed the findings of the Kultivate (2011) Project [13]; Gray describes a workflow tested in conjunction with the researcher which was ‘designed to support the archiving of live artwork’. This resulted in the creation of a ‘granular catalogue record (or ‘score’)’ which included, ‘videos of the performance, video interviews with the artist, scans of related promotional material, [and] digital photographs of objects involved’ [14].

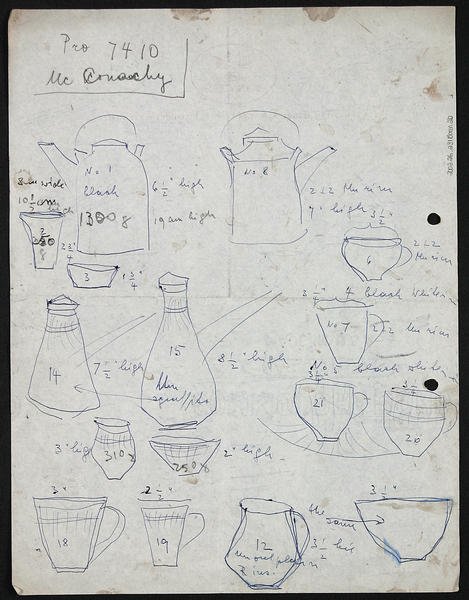

Figure 4: Lucie Rie, Loose sheet with sketches of pots in blue biro.

Lucie Rie Archive, Craft Study Centre [further details][9]

Digital and physical, visual arts research data can take the form of digital files or physical objects. One of the nine EPSRC Expectations (2011) [15] mentions physical research data, ‘Publicly-funded research data that is not generated in digital format will be stored in a manner to facilitate it being shared in the event of a valid request for access to the data being received…’. The implication is either that a programme of digitisation is required for future research data, or that at least metadata records will be required for physical research data which include access information. A useful point to consider is that the research data of today may well be the special collections of the future (cited in Murtagh, 2011 [16]). Taking the example of the Stanley Kubrick Archive which is housed in the University Archives and Special Collections Centre, University of the Arts London, ‘...a staggering collection of some 800 large boxes containing scripts, stills, props, posters, costumes, documents, equipment and a vast library of books…’ [17]. This was evidence from the project team, where one interviewee noted:

‘...I’m just like anyone else I’ve got boxes of stuff, I’ve got a garden shed and then I’ve got files, I’ve got electronic files and I’ve got physical files, I’ve got ring binders full of clippings, full of photographs, and I’ve got documents of exhibitions that I’ve been in, I’ve got catalogues of exhibitions I’ve been to…’.

Figure 5: Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie, Small vase, used as a sample for an ash glaze, stoneware, box ash glaze, 1930s. Craft Study Centre [further details] [9]

As previously indicated, the definition of research data in the visual arts, cropped up informally several times throughout the lifetime of the project, and at its conclusion it was defined as:

“Evidence which is used or created to generate new knowledge and interpretations. ‘Evidence’ may be intersubjective or subjective; physical or emotional; persistent or ephemeral; personal or public; explicit or tacit; and is consciously referenced by the researcher at some point during the course of their research. As part of the research process, research data may be collated in a structured way to create a dataset to substantiate a particular interpretation, analysis or argument. A dataset may or may not lead to a research output, which regardless of method of presentation, is a planned public statement of new knowledge or interpretation.”[18].

The nature of research data presents a unique series of challenges to researchers, curators and institutions seeking to collect, manage, use and preserve research data in the visual arts, many aspects of which the project team when on to explore further.

![Figure 6: Rhodes, Zandra (1981). The Renaissance/Gold Collection [Jacket] © Zandra Rhodes 2012 Figure 6: Rhodes, Zandra (1981). The Renaissance/Gold Collection [Jacket] © Zandra Rhodes 2012](/images/issue71-garrett-et-al/figure6.jpg)

Figure 6: Rhodes, Zandra (1981). The Renaissance/Gold Collection [Jacket]

© Zandra Rhodes 2012

User and Technical Analysis

Following the publication of the environmental assessment report, the Technical Project Manager embarked on a series of interviews with the four Project Officers and information technology staff at each partner institution, with the purpose of creating a user requirement for the curation and preservation of research data in the visual arts. Based on the user requirement, the team identified seventeen potential systems which could be relevant to the curation and preservation of visual arts research data. Using a basic scoring mechanism, based on one point per requirement, five of these systems were identified as potential solutions and selected for further detailed analysis. Further analysis was undertaken by means of an online questionnaire whereby the Project Officers were asked to prioritise each of the requirements using a scoring method in order to calculate a more accurate score for each of the five potential solutions. As a result EPrints, figshare and DataStage were selected as the preferred best options for partners to consider when selecting their system for curating visual arts research data.

However, none of the three systems provided a single solution which could fulfil all the requirements of researchers, research teams, and their host institutions. Therefore, to appreciate and understand fully how best to meet the research data management requirements of researchers and their institutions, it was recommended that two pilots were undertaken in parallel: an integration of figshare with EPrints; and DataFlow's DataStage with EPrints.

In addition to the planned user and technical review, the project team was asked by the Steering Group to develop an IT costing model. This was circulated and used by the partners to estimate the infrastructure costs associated with research data management over the short to long term. The model was also disseminated more widely and generated considerable interest from the wider sector.

Following ratification of the technical analysis by the partners, the team set up two pilot services. The first was an instance of DataStage to EPrints and a second, an instance of figshare with EPrints. The partners undertook an evaluation of both these instances and it was agreed that neither was a viable option within the visual arts. Therefore it was agreed, at a late stage in the project, following the adopted methodology, to pilot an instance of CKAN with EPrints.

The team discovered that the combination of CKAN and EPrints was the most likely infrastructure solution for the visual arts because: of its sustainability model; being open-source; while its licensing model was more flexible than the previous options which had been considered. However, ultimately, when trying to move beyond the pilot, the team was confounded by a series of technical integration challenges and finally by the deadline of the project itself, leaving project partners better informed and to continue to explore the issue of infrastructure.

Institutional Embedding

Sustainability was a core element of the project; the partners adopted an embedded approach with Project Officers from each of the four institutions being seconded from existing posts. This ensured that emerging knowledge, skills and practice were embedded and sustained within each institution. In addition, the project benefited from the appointment of senior representatives at each partner institution to provide strategic leadership and governance at a high level across their respective institution.

Policy Formation

This was a highly complex process for each partner, partly due to terminology and lack of clarity over the nature of research data in the visual arts but also due to lack of awareness of the requirements of funders, and the costs involved. Policy formation was highly dependent upon existing institutional regulations, contractual obligations, practices, policies and procedures, which in some instances required consideration and review beforehand. This was compounded by staff changes and other demands and priorities which faced institutions. However, directed by emerging funder requirements, the project team reviewed the emerging policy landscape across the sector and with the support of the Project Sponsors, all four partner institutions were successful in developing high-level research data management policies, three of which were approved by their respective institutions by the conclusion of the project, whilst the final policy was working its way through the approval system.

Skills Development

The team developed two session outlines, each one hour in duration. The first looked at the basic principles of research data management in the visual arts and the second focused on the creation of a research data management plan. This was developed by each partner into a pilot course using appropriate content and resources from their respective institutions bearing in mind their particular organisational practices, process and disciplinary areas. Each partner worked with different groups, so across the project, participants included early-career researchers, research students, established researchers and professional support colleagues from a range of departmental perspectives. Feedback from the participants was favourable, and evaluation demonstrated that their understanding of research data management had improved or improved considerably. Facilitators also noted that participants appreciated the importance of communication between departments and the need for a cohesive institutional approach.

The materials and feedback were then shared and reviewed by the project team and a series of online resources collated to form three digital toolkits to be hosted online and shared with the wider Higher Education community.

![Figure 7: Rie, Lucie (1950s). Set of jug and two cups and saucers [Ceramics] © Mrs. Yvonne Mayer/Crafts Study Centre 2012 Figure 7: Rie, Lucie (1950s). Set of jug and two cups and saucers [Ceramics] © Mrs. Yvonne Mayer/Crafts Study Centre 2012](/images/issue71-garrett-et-al/figure7.jpg)

Figure 7: Rie, Lucie (1950s). Set of jug and two cups and saucers [Ceramics]

© Mrs. Yvonne Mayer/Crafts Study Centre 2012

Conclusion

The project has successfully accomplished its stated outcomes: we have a much better understanding of research data in the visual arts, and the challenges it presents for its collection, curation, use and preservation; the partners have developed and adopted research data management policies; the team has undertaken an extensive review of user requirements and possible technical solutions; and a series of workshop and training materials have been developed and piloted to inform, support and guide practice.

Of equal importance was the unexpected benefits accrued throughout the project. First, the partners have benefited from the development of strong relationships between departments, and knowledge, skills and practice have been informed, developed and embedded both at an operational and strategic level. Second, the collaborative nature of the project has provided a sound basis on which to explore and share common issues and problems, with all of those involved reporting that the collaboration has been highly effective and useful. One senior manager reported:

I have benefited by learning about the techniques other institutions have used to encourage their artists to collect research data and the progress that they have made in establishing data repositories specific to the needs of creative practice researchers.

![Figure 8: Degas, Edgar (1878-1879). Jockeys before the race [Painting]

©The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham Figure 8: Degas, Edgar (1878-1879). Jockeys before the race [Painting]

©The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham](/images/issue71-garrett-et-al/figure8.jpg)

Figure 8: Degas, Edgar (1878-1879). Jockeys before the race [Painting]

©The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

Third, the project has forged greater links with visual arts researchers and engaged them in considering and reflecting upon their practice. However, conversely, partners reported that the project had been extremely helpful in understanding the nature of research data, seeking the experience of visual arts researchers and in seeing examples of practice. One noted that, ‘It was good to see the examples of actual projects and activities and hear what the artists involved considered to be their “data”. I feel that I would now be able to talk to visual artists about managing their research data without feeling like quite such an ignorant fool.’ Fourth, the project sponsors and high level institutional support was a requirement of the project, and this proved to be essential to both the project success and also embedding and sustainability within the partner institutions. In practical terms considerable progress was made in terms of policy formation and skills development, and they provided awareness and direction to the issue of research data management both within their respective institutions but also more widely across the sector.

However, significant challenges remain. Most immediate is the lack of a comprehensive technical solution, which addresses the needs and behaviour of visual arts researchers and research teams, and meets the requirements of curators, institutions, funders and the wider community. Following on, the most important challenge is to embed effective research data management skills within practice. A small step has been made in this direction already. Working with the University for the Creative Arts, the Glasgow School of Art and Falmouth University, the team has been successful in securing funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council to create a skills development package to support postgraduate and early careers researchers within the visual arts to manage their research data effectively. But further work will undoubtedly be needed on an ongoing basis as knowledge and practice emerges while the knowledge and skills of librarians, curators, information managers and senior managers will also need to be addressed.

References

- KAPTUR (2011-13) Project Web site http://www.vads.ac.uk/kaptur/index.html (retrieved 18 June 2013)

- RCUK (2012). RCUK Proposed Policy on Access to Research Outputs. Online at: http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/research/Pages/outputs.aspx (retrieved 3 June 2013)

- DataCite (2012) Repositories http://datacite.org/repolist (retrieved 4 June 2013)

- DCC (2011) UK Institutional data policies http://www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/policy-and-legal/institutional-data-policies/uk-institutional-data-policies (retrieved 4 June 2013)

- Garrett, L. (2011) KAPTUR Project Proposal http://www.vads.ac.uk/kaptur/ (retrieved 4 June 2013)

- AHRC (2012) Research Funding Guide http://www.ahrc.ac.uk/SiteCollectionDocuments/Research-Funding-Guide.pdf (retrieved 5 June 2013)

- MRC (2011) MRC Guidance on Data Management Plans. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/Ourresearch/Ethicsresearchguidance/datasharing/DMPs/index.htm (retrieved 19 June 2013)

- Garrett, L., Gramstadt, M-T, Burgess, R., Murtagh, J., Spalding, A. and Nadim, T. (2012) Jisc-funded KAPTUR project environmental assessment report. Visual Arts Data Service (VADS), a Research Centre of the University for the Creative Arts http://www.research.ucreative.ac.uk/1054/ (retrieved 3 June 2013)

- Visual Arts Data Service: Crafts Study Centre Collections http://vads.ac.uk/collections/CSC.html (retrieved 14 June 2013)

- Howard, T., Darlington, M., Ball, A., Culley, S. and McMahon, C. (2010) Understanding and Characterizing Engineering Research Data for its Better Management. University of Bath http://opus.bath.ac.uk/20896/1/erim2rep100420mjd10.pdf (retrieved 3 June 2013)

- Mey, K. (2010) Creativity, Imagination, Values - why we need artistic research. In: Textures, the 6th European meeting of the Society for Literature, Science and the Arts, Riga, Latvia, 15-19 June 2010 (Unpublished)

- Griffiths, M. (2010) Research and the Self. In: Biggs, M. and Karlsson, H. eds. The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts. Abingdon: Routledge, 167-185.

- KULTIVATE (2011) KULTIVATE Project Outputs http://www.vads.ucreative.ac.uk/kultur2group/downloads/ (retrieved 18 June 2013)

- Gray, S. (2011) Documenting Performance Art for the Archive. Online at: http://www.vads.ac.uk/kultur2group/casestudies/Bristol2011.pdf (retrieved 4 June 2013)

- EPSRC (2011) EPSRC Policy Framework on Research Data. Online at: http://www.epsrc.ac.uk/about/standards/researchdata/Pages/policyframework.aspx (retrieved 3 June 2013)

- Murtagh, J. (2011) An arts perspective: day two and three - the sixth DCC Roadshow on data management http://www.dcc.ac.uk/news/arts- perspective-dcc-roadshow (retrieved 4 April 2012)

- Kemp, P. (2006) The Kubrick Legacy. In: Alumni Magazine, University of the Arts London, Issue 5 Spring/Summer 2006, pp. 8-17.

- Garrett, L. (2013) Defining Research Data in the Visual Arts http://kaptur.wordpress.com/2013/01/23/what-is-visual-arts-research-data-revisited/ (retrieved 18 June 2013)

Author Details

Email: lgarrett@ucreative.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.research.ucreative.ac.uk/profile/684

As Director of the Visual Arts Data Service, a Research Centre of the University for the Creative Arts, Leigh’s research interests lie in the collection, management, discoverability, engagement, preservation and sustainability of digital assets, particularly where they support and enhance learning, teaching and research in the visual arts. As such, Leigh has been Project Director and Principal Investigator for a number of external and internal research projects including: Look Here! (2010 - 2011), Kultivate (2010 - 2011), UCARIS (2010 - 2014), eNova (2011), the Collections Review (2011 - 2012), Spot the Difference! (2011 - 2012), KAPTUR (2011 - 2013), iTrace (2012) and VADS4R (2013-14). He has also supported a number of other projects across the sector including: the Jisc-funded KeepIT Project (2009 - 2010), Higher Education Academy's Open Educational Resources Project (2010), AHRC Digital Dance Archive (2010 - 2011) and the Zandra Rhodes Digital Study Archive (2011 - 2013).

Email:mgramstadt@ucreative.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.research.ucreative.ac.uk/profile/60

Marie-Therese Gramstadt is currently managing the KAPTUR Project (Jisc, 2011-13) working with Goldsmiths, University of London; The Glasgow School of Art; University of the Arts London; and University for the Creative Arts, to improve the management of arts research data. She is also a Researcher and Digital Cataloguer for the Zandra Rhodes Digital Study Archive (Jisc, 2011-13), making use of her MA in the History of Dress (Courtauld Institute of Art). Marie-Therese has recently re-joined the Crafts Study Centre to work on the SCARLET+ Project using augmented reality with the Muriel Rose Archive (Jisc, 2012-13). Previous projects include: Kultivate (Jisc, 2010-11), eNova (JISC, 2011) and three Learning and Teaching Research grants (2010, 2010-11, 2011-12).

Email: csilva@ucreative.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.ucreative.ac.uk

Carlos Silva’s research interests focus on the areas of research information systems, cloud technologies, institutional repositories and software development, specifically their application to practice within visual arts. As such, Carlos has undertaken a range of user and technical research projects, including: Enhancing VADS (2008-2009), Look Here! (2010-2011), Kultivate (2010-2011), UCARIS (2010-2014), eNova (2011), KAPTUR (2011-2013) and the Zandra Rhodes Digital Study Collection Project (2012-2013). He also sits on the HEFCE Data Collection Steering Group representing the University and GuildHE.

Email: maspalding@ucreative.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.ucreative.ac.uk

Anne Spalding is currently managing UCA Research Online and working on the development of this resource in liaison with the University's research community and other stakeholders. Anne has recently worked on the Jisc-funded KAPTUR Project (Jisc, 2011-13), as institutional Project Officer for the University for the Creative Arts, and previous projects including Kultivate (JISC, 2010-11), eNova (Jisc, 2011).