Improving Evaluation of Resources through Injected Feedback Surveys

Terry Reese suggests a novel approach for providing intercept survey functionality for librarians looking to simplify the gathering of user feedback for library-provided materials.

Assessment of electronic resources has long proven a difficult challenge for librarians when looking to make collection development decisions. Often, these decisions are made by looking at usage statistics provided by the vendor, and through informal conversations with selected faculty within affected disciplines. The ability to capture point-of-use information from users remains a significant challenge for many institutions. The purpose of this paper will be to suggest a novel approach to providing intercept survey functionality for librarians looking to simplify the gathering of user feedback for library provided materials.

Background

Libraries have long excelled at utilising a wide range of tools when attempting to assess electronic resource usage. Initiatives like COUNTER (Counting Online Usage of Networked Electronic Resources [1] and SUSHI (Standardized Usage Statistics Harvesting Initiative [2] have provide librarians with new tools and more reliable methods for analysing raw usage data. Because of the availability of these data, library assessment efforts tend to focus most intently on these types of vendor- provided usage statistics. Utilising statistics provided, librarians can make broad assumptions on the general usefulness of a set of resources, which helps them understand who is currently using specific content. However, while these broad assessments can help to determine the general overall usage of a set of resources, they have a difficult time in capturing the actual impact of those resources on students’ or faculties’ current and future research.

While statistics can give broad snapshots of usage, libraries have begun to shift their metrics when assessing electronic resource purchases to metrics of impact. To measure impact, librarians need a very different set of information, information not found in usage statistics but provided directly by users at the point of need. Typically, this type of information would be gathered through the development of surveys that could be presented to the user while working within a specific electronic resource. However, these types of injection surveys typically are difficult and unwieldy to create and manage, often making them beyond the reach of many libraries to implement – but they do not have to be. The purpose of this article is to describe a novel approach to developing customised injection surveys around an institution’s proxy server, thereby providing libraries with a new method of collecting direct user feedback to determine the real impact of specific electronic collections.

The development of this approach came out of the Oregon State University Libraries (OSUL) participation in the MINES [3] for Libraries® programme out of StatQual [4]. OSUL has participated in the MINES survey over two previous years as a way to capture user-provided feedback on how electronic resources purchased by the Library were being employed by students and faculty staff to support their non-instructional research activities. The MINES survey is designed to run over a period of 12 months with the expectation that the survey will be injected into all workflows where users can retrieve electronic resources. Because of the scope and breadth of the survey, and the scope of the materials covered, the survey’s implementation and presence can represent a significant project for a library.

In order to participate, OSUL worked with the MINES survey administrators to develop a simple survey to capture feedback both about the user and why the user was utilising the information provided by the Library. Working with the MINES survey administrators, OSUL then evaluated the current access points available to users seeking to access electronic information in order to determine the optimal location within the process to inject the survey. After a careful examination of the Library’s workflows, it was determined that the Library’s proxy server, EZProxy [5], represented the most straightforward point of access. Since all the University’s electronic resources provided by the OSUL always filter through the proxy server, it represented the most logical point of mediation within the resource delivery workflow where we could be certain of capturing a user’s feedback.

In order to make the MINES survey work, the proxy URLs needed to be rewritten so that users were sent first, through the survey, then redirected back to the proxy server to access the individual content. Consulting with the MINES survey administrators, OSUL discussed a number of different methods used by other institutions participating in the survey. By and large, the most common method of achieving this type of redirection was to manually rewrite the necessary URLs found within the Library’s various online systems. For the process to be successful, this meant rewriting tens of thousands of URLs within the Library’s catalogue, Web site and external applications to support the injection of the survey URL. Moreover, at the end of the 12-month survey period, it meant rewriting those same URLs within the Library’s catalogue, Web site and external applications to remove all references to the MINES survey. During the OSUL’s two previous experiences with this survey, this URL rewriting process proved to be fraught with errors as content would sometimes be rewritten incorrectly or failed to be found and corrected at the survey’s end, ultimately affecting the user’s ability to access the information. Moreover, new resources purchased during the survey period were not often set up to work with the survey, so access to these resources was largely absent from the final survey results.

Designing a New Workflow

In 2012, the OSUL decided that it would participate in the MINES survey for a third time. However, since the previous surveys, the electronic resources environment had undergone major changes. In previous years participating in the survey, the OSUL has been in the process of transitioning much of our journal access to electronic resources – but for many of our patrons, electronic journal access was still the secondary access point. Today, that is no longer the case. By and large, the OSUL does not purchase print scholarly journal publications, meaning electronic access is the primary method of access for scholarly communication at OSUL. In previous years, the number of URLs in need of rewriting was high, but fairly manageable. By and large, such URL rewriting would be limited to the Library catalogue, the Web site and a handful of third-party tools. Today, not only would it be very difficult to determine the number of URLs that would need to be rewritten, but the Library’s use of external tools and systems that provide access to our electronic resources are widely varied and difficult to quantify accurately. Essentially, the amount of content that the OSUL purchases and manages for the University had become much too large and too diverse to support the previous survey methodology. A new process needed to be developed that did not involve the rewriting of any data, and would continue to support the wide range of resources currently accessing the OSUL’s content.

In looking at all the ways the OSUL’s electronic resource landscape had changed in the three years since the last MINES survey, one specific piece of the puzzle had stayed the same. While the OSUL licenses and provides access to many more resources, the centrality of the OSUL’s proxy server within the access workflow has remained the same. As in previous years, the proxy server remains the primary point of access for all electronic resources served by the Library. However, in the intervening years between the last MINES survey, the function of the proxy server had changed as well. Since the last survey, the proxy server’s functionality has been expanded to support a number of different applications and workflow processes. For the OSUL, the most radical change revolved around OCLC’s WorldCat Navigator [6] Project and its integration with the proxy server to support lending with our consortial partners using the product. Moreover, additional integration projects with our discovery system, locally developed applications, and development carried out by departments at the University outside the Library made it imperitive that we consider the broader effects that any change to the proxy server’s behaviour might have upon our users. While the proxy server certainly remained the single best access point for implementing an injection survey, the fact was that the proxy server’s role within the Library had expanded, making it difficult to work directly with the component. To overcome this difficulty, the Library took a novel approach to restructuring our proxy workflow, essentially creating a public and private proxy configuration that allowed the Library to rethink how we could support these types of injection style surveys while preserving transparent access to our resources.

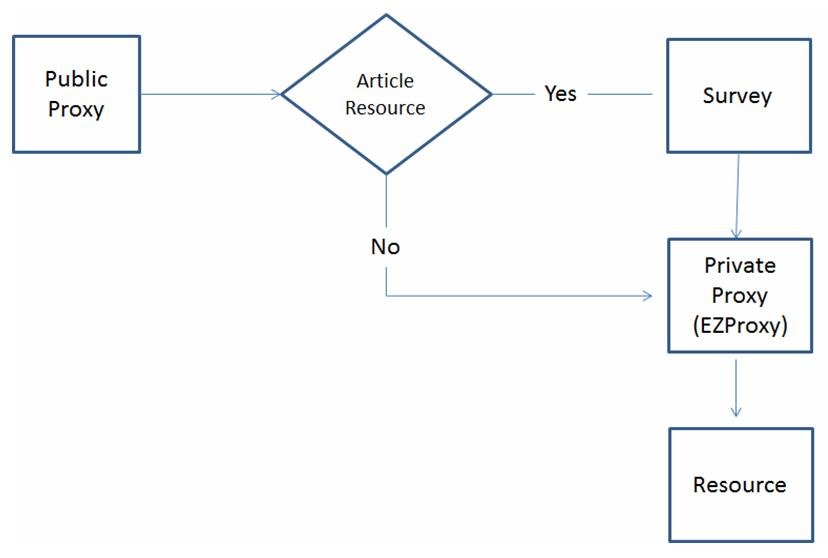

The overall goal of this project was to create a generic infrastructure that would allow the Library to support not just the MINES survey for the next 12 months, but to provide a generic surveying framework that could be used as part of the Library’s resource assessment toolkit. Looking specifically at the proxy workflow, the OSUL proposed modifying our current workflow where EZProxy was the front-facing proxy – to a workflow where EZProxy would be proxied and traffic would be redirected to the appropriate workflow component, based on the context of access. The new public proxy would act as a decision engine, redirecting traffic to the survey application or EZProxy, based on the type of access being requested. The survey application then would manage the various surveys being run by the Library, determining when to display a particular survey or simply redirect the user through the private proxy and to the specified resource. The diagram in Figure 1 captures the new simplified workflow being operated by the Library.

Figure 1: Workflow diagram

The benefit of this approach is that it allows the Library to modify the underlying proxy workflow without having to change any of the underlying proxy URLs currently scattered throughout the Library. For example, if the proxy URI for an institution was http://proxy.domain.edu, this URL would remain valid. Within this workflow, the proxy URL would be transferred to the public proxy, with the private proxy taking on a new URL. This approach allows all the previous URLs in use by the Library to remain valid, while at the same time providing the hook needed to support direct user assessment when resources are requested.

Furthermore, implementation of the new workflow proved to be relatively straightforward. Rather than attempt to work with EZproxy, the OSUL implemented a common Apache [7] proxy to function as our public proxy server. Apache made a lot of sense for this project due to its flexibility and support for proxy transactions. For our implementation, the OSUL utilised the mod_proxy and mod_rewrite modules to preserve state and redirect content to the appropriate point in the workflow. For example, the OCLC WorldCat Navigator Project utilises our proxy for user authentication so requests made by this service need to pass straight through to the EZproxy server and forgo the server (since these requests are machine-automated).

RewriteEngine on

RewriteRule ^/userobject/(.*)$ http://ezproxy.proxy.library.oregonstate.edu/userobject/$1

RewriteRule ^/userobject(.*)$ http://ezproxy.proxy.library.oregonstate.edu/userobject$1

Using a simple set of rewrite rules like those above, the Apache proxy would be able to preserve the expected access and functionality of the Navigator component.

RewriteEngine on

RewriteRule ^/login(.*)$ http://osulibrary.oregonstate.edu/survey/ics/login.php$1

Moreover, this same process can be adopted to allow the Apache proxy to emulate the EZproxy URL structure, allowing the Apache proxy to preserve and support all existing URLs used by the Library to access content. By making a handful of simple modifications to the proxy workflow, the OSUL was able to develop a secondary survey engine that could then be injected into the process whenever necessary without the need to alter any current access points.

Consequences of the New Workflow

While the new proxy workflow solves some specific difficulties, it also creates some new ones. In general, the problems encountered divided into one of three categories:

1. Maintaining Secure Transactions

While many of the resources that OSUL licenses do not require secure transactions to retrieve scholarly content, a number of our high-use resources do. In our previous workflow, EZproxy easily supported this use case. However, by placing EZproxy behind a proxy, the new workflow had to maintain a secure transaction throughout the various steps of the workflow. To ensure that the transactions remained secure, each server within the workflow was given a certificate and placed within the same domain. So, the resulting workflow comprises three secured servers, running under the same domain, i.e.:

- public server: http://proxy.domain.edu

- survey server: http://survey.domain.edu and

- private proxy: http://private.proxy.domain.edu

By keeping the workflow servers under the same domain, the process maintains a secure session throughout the retrieval process, thereby preventing users from receiving unsightly access errors or errors related to server security.

2. Supporting External Applications

The primary purpose of the public proxy server is to act as a decision engine and redirect user traffic to the appropriate resource based on the request context. In many cases, the context of the request can be determined from the URI allowing the server to redirect the user’s request using a simple URL rewrite. However, we found other instances where this type of redirection was insufficient. The most difficult of these to overcome was OCLC Navigator’s integration with EZproxy for lending. While the public proxy could be used to redirect the request correctly, the OCLC software would not take the response back from the private proxy due to the URI mismatching. In this case, the only way to solve the issue was to reset our proxy URL in OCLC’s Navigator product to the private proxy URL.

3. Supporting Special EZProxy Syntax

While links through the proxy server are largely regular, we found a small number of URIs to resources like Gartner, which represent special content made available by EZProxy. These URIs do not rewrite in a regular manner and presented special problems when being served through the survey application.

Therefore, employing the new workflow, OSUL was able to re-implement the MINES survey instrument for the 2012-2013 academic year in a matter of hours. What is more, the process has proved to be much more reliable than previous attempts which relied on numerous processes and on staff rewriting tens of thousands of URLs. It has been far more transparent for both the staff and the Library’s patrons.

Survey Tool

Redesigning the proxy workflow allowed the Library to take a closer look at how it could potentially support a more user-directed assessment programme. Like many libraries, OSUL is looking for new ways to demonstrate not just use of services, but their impact on our user populations. The ability to interact directly with users as they utilise specific services or resources represents a unique opportunity which had not been available to the Library in the past.

Due to some of the time constraints of the MINES survey, the initial version of the survey tool [8] is relatively straightforward. Utilising PHP for quick development, the application was developed employing a basic model/view structure. Utilising a master ‘controller’, the application imports defined journal lists (for targeted surveys) as well as a global survey option that is then used to determine and generate the appropriate survey instrument. Survey templates are harnessed to support rapid survey generation and JQuery is employed to provide support for multiple-user interfaces.

While the initial version of the survey tool was created primarily to support the MINES survey instrument, the tool is currently being revised to support a much wider implementation at OSUL and to support a wider range of contexts for its implementation. At present, the primary ‘controller’ works to emulate the EZproxy URL structure so that these URLs can be preserved. In the future, the entry point into the tool will be abstracted further so that the survey instrument can emulate practically any URL structure and support the ability to capture user feedback from a wide variety of tools and services.

Targeted Surveying

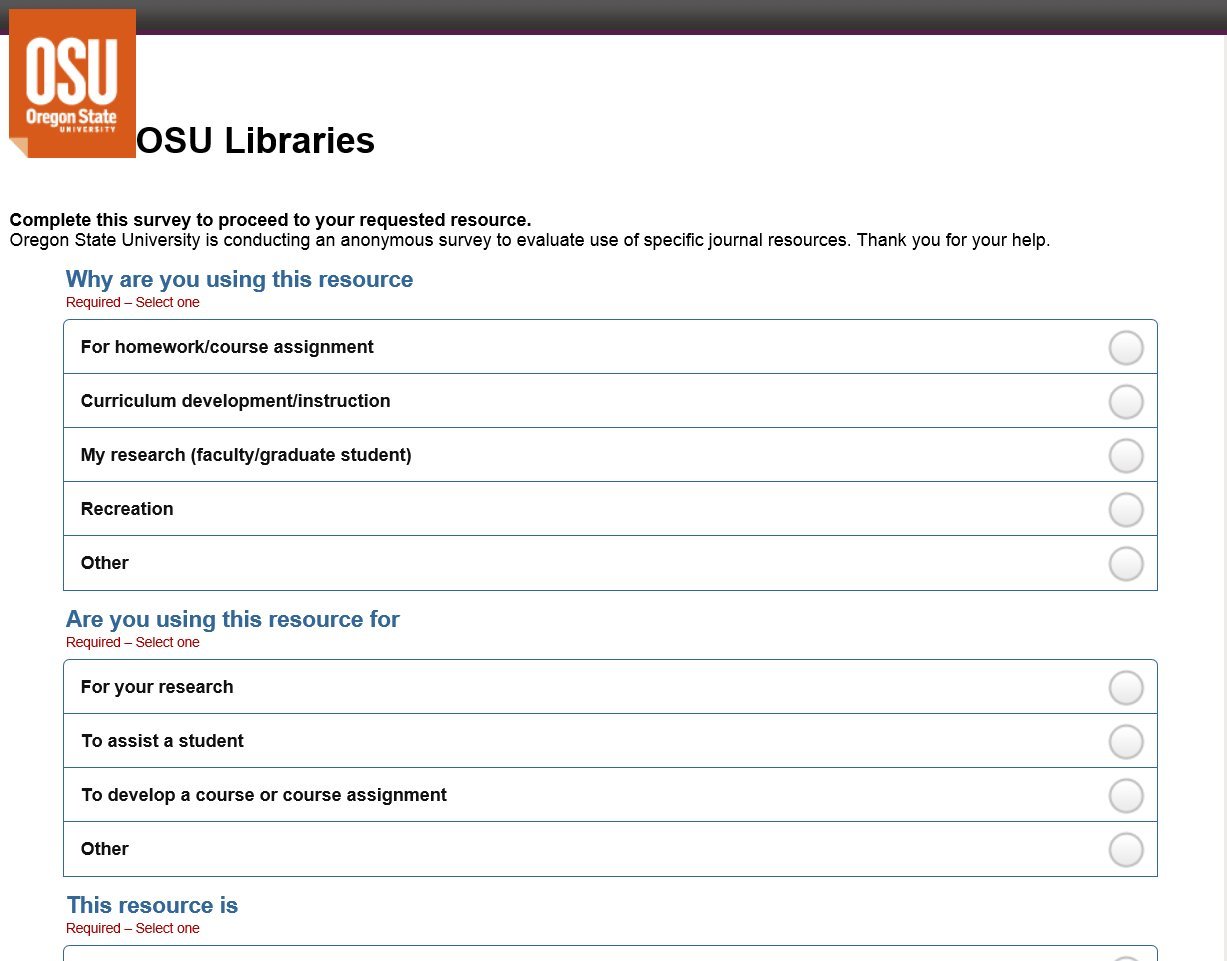

One of the perceived benefits of the new survey methodology is the ability to run multiple surveys over the same period that target specific resources. While preparing the MINES survey, we recognised that the new workflow could potentially change the way collection development librarians procure feedback when evaluating resources, as well as provide new tools for broader assessment of resources and services provided by the library. At OSUL, there is a specific interest in determining the long-term feasibility of this new methodology to assist in making collection development decisions. As collections development librarians evaluate specific electronic resources for continued access or withdrawal, the ability to survey users directly to capture information related to overall impact would provide a new rich set of metrics to help guide those collection decisions. As a proof of concept, OSUL developed a survey that would only display when accessing specific library science-related resources.

Figure 2: Proof of concept specific journal survey

To evaluate the feasibility of such an approach, a proof of concept survey was created, with the intention of targeting a very specific set of niche resources utilised primarily by humanities students and scholars. The proof of concept allowed OSUL to test a number of different aspects of the process:

- It allowed the Libraries to introduce this notion of user-targeted feedback within the academic setting and gauge how users responded to this intrusion. This was a serious concern. Unlike the MINES survey which runs over discrete periods for a couple hours a day, this feedback implement was designed to run over extended periods, potentially exposing users to multiple instances of the instrument. Attempting to balance the Libraries’ desire to capture a user’s feedback regarding impact against the danger of over-surveying a specific user population is one of the issues librarians at OSUL will be continuing to explore.

- It allowed the Libraries to evaluate the workflows around developing new surveys and the flexibility of the templates. While the survey tool was designed to be easy to understand and implement, there is an assumed level of familiarity with PHP, HTML, and CSS, but resulted in the ability to create very complex surveying instruments. However, to encourage wide-spread use among the faculty, a more straightforward method of survey design probably needs to be developed – preferably one that integrates well with existing toolkits and reuses existing expertise. To that end, OSUL will be exploring integration with Qualtrics [9], utilising its API, enabling faculty staff already familiar with the tool to create their own surveying instruments and integrate these tools into the application.

- The process allowed OSUL to begin looking at how user data might be able to be evaluated in aggregate between departments and potentially organisations. While the tool was initially developed to measure and capture qualitative information the better to determine true user impact of resources for a specific set of resources, the proof of concept process raised a number of interesting questions concerning the ability to aggregate this type of information around institution types, location and focus. It is our hope that the Libraries will be able to work with a handful of peer institutions to determine if this approach could be used to inform shared collection development decisions as well as track research trends among similar organisations.

The proof of concept demonstrated that it was possible to provide targeted user surveys for specific journal resources. Working with the survey application, a list feature was implemented allowing librarians to define a set of journal URLs and customised survey forms that could then be employed to capture this type of individualised feedback. The long-term goal of this process is to obtain a clearer understanding of how resources and services, provided by the Libraries, affect research on the campus, and, we hope, provide a better set of metrics to inform collection development decisions.

Having tested the proof of concept and evaluating the type of rich information captured over a short two week period, there is definitely significant interest to move forward and conduct a more rigorous pilot programme in the Summer of 2013. The formalised pilot programme will seek to investigate the quality and scope of data that can be captured, as well as the long-term viability of this type of use.

Conclusion

As service organisations, libraries will always play the role of information provider for their users. However, how libraries assess the use of this information is changing. While raw usage data used to be the gold standard for making collection development decisions, the move to try and measure the impact of the resources libraries provide to their patrons offers libraries new opportunities to evaluate novel ways of collecting user feedback. At OSUL, this has meant rethinking how our users’ access information provided by the Library, and considering innovative approaches to exploiting those workflows to encourage a wider conversation with our patrons. And it is through these conversations that we hope not only to understand the true impact that our library is having on users, but also to identify where we could be doing better.

References

- COUNTER (Counting Online Usage of Networked Electronic Resources) http://www.projectcounter.org/

- SUSHI (Standardized Usage Statistics Harvesting Initiative) http://www.niso.org/workrooms/sushi see also:

Paul Meehan, Paul Needham, Ross MacIntyre. "SUSHI: Delivering Major Benefits to JUSP". November 2012, Ariadne Issue 70 http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue70/meehan-et-al - Martha Kyrillidou, Terry Plum & Bruce Thompson (2010): Evaluating Usage and Impact of Networked Electronic Resources through Point-of-Use Surveys: A MINES for Libraries™ Study, The Serials Librarian, 59:2, 159-183.

- STATSQual http://www.statsqual.org/

- OCLC EZProxy authentication and access software http://www.oclc.org/ezproxy/

- OCLC WorldCat Navigator http://www.oclc.org/navigator/default.htm

- Apache HTTP Server Product http://httpd.apache.org/

- OSUL Survey Tool Source https://github.com/reeset/ics

- Qualtrics http://www.qualtrics.com/

Author Details

Email: reese.2179@osu.edu

Web site: http://blog.reeset.net

Terry Reese is the current Head of Digital Initiatives at The Ohio State University Libraries. In this role, he oversees the strategic development of The Ohio State University Libraries digital initiatives programme. His research interests include metadata analysis, data mining and visualisation, and system architecture design. Mr. Reese was the previous holder of the Gray Family Chair for Innovative Library Services at Oregon State University. It was in this role that this paper was developed.