Digitizing Wilfrid

PH How did the WWW1 JTAP seminars get started?

SL A long time ago we did a set of Hypercard stacks on Isaac Rosenberg, which I converted for the web in January ‘95, and then when the JTAP call came out I thought that we could expand the tutorial and make four tutorials. And then we had all the archive nearby: we thought we would tackle the idea of creating both online tutorials and a digital archive which lecturers could use.

PH Your first virtual seminar was a study of Isaac Rosenberg’s ‘Break of Day in the Trenches.’ Any particular reason why you began with Rosenberg?

SL We did the Hypercard stack in 1992. We chose the First World War because in the arts the things that had been concentrated on had been classics and medieval literature; what that told us was that hypertext lent itself well to something which you could embed in rich cultural surroundings - history, art and so on. The First World War is a very popular subject, and we went for Rosenberg because he isn’t that widely studied - he is a popular poet, but nowhere as popular as Sassoon or Owen. Probably one of the better poets of the war. So that’s why we started with him and the First World War. I’d been playing with it and Hypercard for so long and when the web came along I wondered how far I could push it. I started thinking more about the design of it.

PH At the time what software were you using to create the seminar?'

SL I don’t think I was using Hotmetal in those days. We started to look at Toolbook, a multimedia authoring tool, for Windows, which does now mount quite easily on the web, but in those days it would have meant developing for Windows only - I’m pretty certain I did all the markup using a word processor. There wasn’t much available at the time - the site isn’t complicated. The graphics were done in Photoshop. I was speaking to Dave Hartland yesterday and he told me that they still use that tutorial at Netskills as an example because they know it is always going to work. When we went to the other tutorials we used Hotmetal - Paul Groves, the research officer for the whole project used it - he did the bulk of the hard work.

PH Were you looking for writers with a smaller than usual output, with a view to digitizing their whole output, or did that idea come later?

SL With Rosenberg I don’t suppose we ever really thought about digitizing the whole collection. There was talk of doing mass digitizations in 1992 when we started with Rosenberg - the Perseus project for example - but that was certainly the reason why we chose Owen: it was a managable corpus, and the bulk of it was in Oxford, or at least a good proportion of it. He was easy to do - you could do him in two years, and we needed only a year to do that side of it.

PH When you began the virtual Seminars were you thinking about producing a comprehensive digital archive of Owen’s work, beyond the poetry, or did that idea come later?

SL I think when we put in the original bid we said we would be digitizing the manuscripts of Wilfrid Owen, but we didn’t put a figure on it. As soon as I went down to the archive itself I realised that would be ridiculous because the archive here also covers his childhood - it has a toy boat, his schoolbooks, and the bulk of it is correspondences with his brother after his death. And I thought we haven’t got much time and very little money so we have to be selective, and we selected the war poems, which I think is justifiable really. The principle period I wanted to cover was his military service. If the money had allowed I would have gone into earlier work. But it was getting across the poetry of the First World War - that is what I wanted to do, what I wanted to digitize. We found then we had money to spare to branch out to do his letters as well, for that period. We knew we wanted to put in the manuscripts, but outside of that.... The Imperial War Museum was interested in collaborating, but we didn't know what level of involvement they would have until a year or so into the project. The photos, the video clips and the sound files all came from them.

PH How did you actually assess that it was feasible to publish all of Wilfred Owen’s manuscripts on the web?

SL We had a handlist for the archive, so we had an idea of the number of items, and then we did a doubling up because we knew we’d have to photograph recto and verso, and then I rang up David Cooper, who is our digitization specialist at the Library Automation Service, and he gave me a rough idea of what that would cost, so we knew we could do all the stuff here; for the two manuscripts at the British Library we knew the rough number of items and I used David’s pricing as a guide and realised we could do that too. But there was a lot of reassessing of the figures as the project went along. There was an internal Oxford grant available which we applied for and got, and then we knew we could expand into all the other stuff as well.

PH Was the project conceived as a way of demonstrating the practicality of digitizing the archives of other writers?

SL Yes. That was what JTAP was all about: you had to demonstrate how the technology could be applied: what we were trying to do was talk about how the web could be used for teaching - we wanted to look at digitization - we knew there were lots of other people using it - what we wanted to explore was how you could make a path through an archive, which is the other facility we created. When you read the JTAP reports, they’re very generic, there is one on online teaching, and the final report of the project talks about the difficulties of digitizing and clearing copyright, not about the First World War much. so it was a bonus that we got all this literary stuff as well.

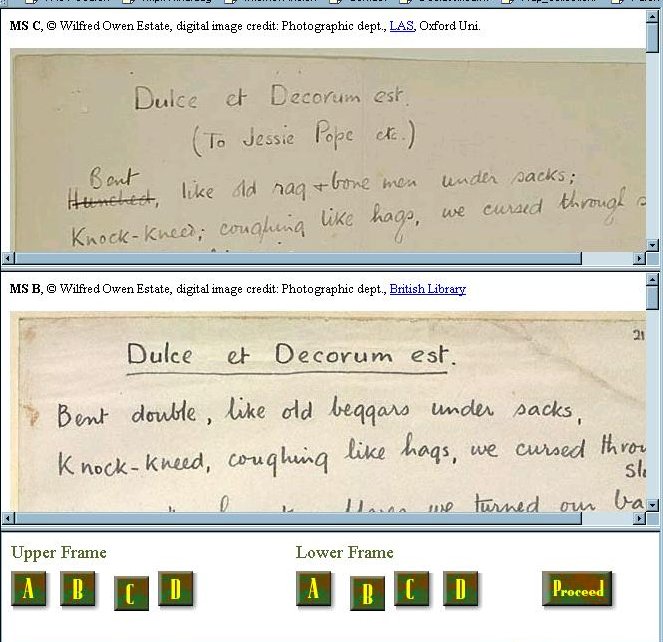

PH The Virtual Seminars series contains a set of frames based pages which allow the user to look at all manuscript versions of Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” and to prepare their own edition of the poem. After that the user can compare their own version of the poem with the Stallworthy edition (‘Oxford Collection’). Do you see this kind of tool developing to the point where real literary research is actually done this way?

SL I could see real research certainly benefitting from the ability to pull in those images next to each other, because they are spread out across the world in three sites so you can’t physically put them together. So it is the old virtual reassembling of a collection. If I was a researcher into Owen I’m not sure the high resolution images would offer too much because the manuscripts are in fairly good condition: there is very little crossing out so heavy you can't read the underlying text, which is where image manipulation might help; all of it is legible. The thing that all Owen researchers want is the watermarks on the paper. Because it can tell you which notepad he was using, and roughly in which order he was writing the poems, and that is what Stallworthy bases most of his findings on. We didn’t digitize those.

PH That’s interesting to me because in exploring the editions tutorial I had settled on a base manuscript with some confidence, on the basis of a comparison of the texts. And then I discovered that Stallworthy had picked a different base manuscript. But I didn’t know that Stallworthy had information about watermarks to go on.

SL That tutorial itself (number three) was one I had in mind a long time ago. I really wanted to do that one because I come from from a medievalist background, where I normally do research, and you always look at primary source material there, and try to get students to look at it quite quickly, whereas modern literature students, certainly at undergraduate level, would just look at an edition. And I wanted to show them what goes into making an edition, and all the decisions which are hidden from them necessarily in a published edition. Which they can then begin to question.

PH Are the digitized manuscripts available on the web digitally watermarked in any way?

No, they’re not. We had a look at digital watermarking and at the time the only system around was digimark, I think, which we could play with: with it we could put large quantities of text in the headers of the images and that sort of stuff, and we couldn’t afford it because in those days you had to register your images with a central service and maintain it. Since the (Mellon) scoping study I’m pretty convinced what we did was correct because watermarking wouldn't have helped us that much. People are probably already pirating the images around the world, but if they appear on the web and we find them they are quite clearly our images - it is a single source item, there is no other copy of that material anywhere in the world. The Owen estate was not concerned with watermarking at all - they were just worried that very high quality images would be available which publishers could rip-off, so when we showed them that they were just working quality images they were quite pleased.

PH You have produced larger versions of the graphics for archival purposes - where are these preserved?

SL We have a large 20 terabyte hierarchical file server here in the university, and that was bought in to preserve the university’s digital ‘intellectual content’. It serves as a back up facility for personal PCs, but also for the types of stuff which David Cooper has done with medieval manuscripts, so they are all stored on that as an archive. Nothing is served from it.

PH Did the tutorials grow out of your own requirements for teaching materials, or were they designed for the use of others from the outset?

SL It was designed with it in mind that others would use them. At that point I hadn’t taught First World War poetry, I’ve only taught it since then. So I didn’t have a course I wanted to slot these straight into. I do now. I think what happened is that I built the course around the tutorials. I used my experience of teaching literature and looked at four different types of teaching: there is the introduction to a genre, which is covered in the first tutorial, and the add-on to that was the bulletin board so that you could then discuss the tutorial - you can go into that at any time. The second one looked at the close reading of a poem - the Rosenberg one, which has the design where you read the poem, comment, go off and look at other materials, and then re-read the poem; the third one is about primary source study, and the fourth about text analysis. So I looked at four areas and designed course material around them. I had the ideas and mapped it out on paper, gave it to Paul and he built the thing. That’s how it worked.

PH Sometimes messages appear on the discussion board which suggest that you are running physical classes using these materials over a number of weeks. Is that right? Do you try to synchronise these classes with the kind of use other tutors might make of these materials?

SL When I ran my class in Hilary term I announced that I was teaching for the next ten weeks. The students contribute to the board, and people hang around and reply to the students. Occasionally you would get a load of messages from what was obviously a class happening elsewhere. But there was no announcement as such. Someone in Texas has got in touch saying she is going to be running a class in November and that she is going to post a reading list before then. Maybe some academics here might pick that up if they are running a similar course at that time, and join up. The experiment we have been running for the past two weeks, a close reading of David Jones 'In Parenthesis,' was announced quite a bit. If that works then that may be something we'll make a bit of a play of, we'll choose another poem or poet and say that in say November we are going to discuss whoever. We might announce it on the front page of WOMDA and ask people to join in. A sort of scheduled mini-conference.

PH What software did you use to create the structure of WOMDA?

SL All the bibliographic files are marked up in SGML, using (predominantly) AuthorEditor. Paul used something else. Occasionally I just used a straight word processor, because it did global replaces quite quickly and easily. The DTD for these files is TEI Lite, slightly modified because it didn't have tags to deal with sound and video. It's a DTD designed for text, so we had to put in a few extra tags. The browse form sends a query via the CGI script which converts it and fires the query into a Opentext 5 search engine, searches the SGML. On the server we have all the SGML files, plus the search engine which searches the SGML files, sends the results back, and the info is converted on the fly into HTML. So when you use WOMDA you are not searching HTML text. That's why the URL's look awful, because the site navigation is managed by CGI scripting. Once you get to the digital object the URLs look fairly standard.

PH Are there plans to use EAD, as was suggested at one point, or is this not a practical proposition at the moment?

SL We looked at EAD, which is popular in Oxford, so it would have been in line with the general direction of the University to use it. We have in the Computing Service and in the Text Archive expertise in putting TEI on the web, ready and running - we were pushed for time - so we went for that option. But we are perfectly happy that in the future we could convert those files to EAD or make a master file and then filter into TEI if we so wish, and the benefit of using EAD would be that it would allow cross-catalogue searching at other institutions. So it wasn't a conscious decision that we didn't want to touch EAD, but that we had experts in TEI here who could get things running quickly - we could use existing scripts at the Text Archive.

PH WOMDA features the ‘path creation scheme’, which allows users to create their own virtual seminars, using the multimedia materials available in the archive. Is this ‘off the shelf’ software, or was it custom scripting?

SL We designed it. A colleague of mine, Chris Stephens, did it. We put something in the original report about making digital paths through an archive. Originally we looked at shopping basket type software you see on commercial sites. We looked at all that, but it wouldn't really work for our purposes. So Chris sat down and just built it. It uses a mixture of Javascript and frames. What happens is that it grabs the URL of whatever is in the right hand window and matches it to whatever text the user has put in, then stores the info in the SQL database, and it sits there till the path is requested. It works beautifully. There are a couple of things we'd like to change - at the moment you can't get into to re-edit an existing path, which is irritating to users trying to improve them.

PH You have said that “the virtual seminar is an attempt to preserve the best aspects of traditional humanities teaching, using the potential offered by new media and new capabilities’. How do you feel the virtual seminars have worked out in practice?

SL I think they did. The purpose of the tutorials was to look at the way you normally teach literature, and to see whether or not that could be replicated in the electronic environment. But I felt it was worth doing only if you could add something you couldn't do in the classroom. When you look at the four tutorials I think they do all add something, even if it is only being able to talk to people all over the world about your ideas. In tutorial three, bringing manuscripts together which students would never get their hands on, obviously, and in tutorial four you can't do manual searches on Owen's poems very quickly, so we sped that process up. With the Archive, well, one thing we want to do more is resource based learning. If you had unlimited money you would always do this, but the money is usually limited. I'm also quite keen on immersing literature in its historical context. The money we got from the UCISA award we've put into digitizing things from the John Johnson collection, which is a massive collection of 20th century ephemera. There is nice stuff there to do with the Great War. That's being digitized at the end of September and will go into the Owen Archive. We are also now mirroring the WW1 Document Archive at Brigham Young, partly at the instigation of the Modern History Faculty so that this material will be available to their students.¶

References

- The JTAP virtual seminars are at: http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/

- The Wilfrid Owen Multimedia Digital Archive is at: http://www.hcu.ox.ac.uk/jtap/

- Break of Day in the Trenches is at: http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/humanities/rose/

- The WW1 Discussion Board is at: http://www.hcu.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/jtap/board/config.pl

- The Final Project Report, On-Line Tutorials and Digital Archives or "Digitising Wilfred" by Stuart Lee and Paul Groves, is at: http://www.jtap.ac.uk/reports/htm/jtap-027-1.html

- The report: Forging Links: The Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature Project by Stuart Lee, Centre for Humanities Computing, University of Oxford is at: http://info.ox.ac.uk/jtap/reports/eurolit.html

- The JTAP Home page is at: http://www.jtap.ac.uk/

- The Oxford University Humanities Computing Unit is at: http://www.hcu.ox.ac.uk/

Author Details

| Philip Hunter Information Officer UKOLN University of Bath Email: p.j.hunter@ukoln.ac.uk |