A Wired Honduran Christmas

Christmas eve we wrapped up a few simple presents, a couple of polystyrene aeroplanes, some puppets, an alphabet colouring book and a kite. We also wrapped up a clockwork Torch. Very useful around here.

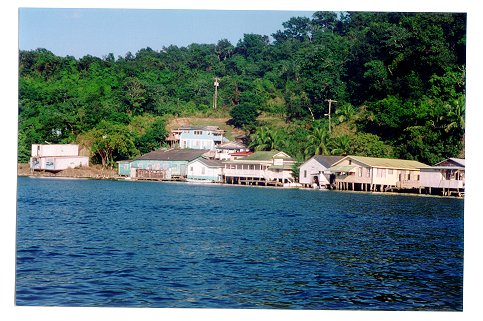

In the morning we were picked up by motor boat and driven over to the house. We left the hotel and passed through the village. Here the islanders all live on the coast. Since the tide doesn't rise much more than a few feet the houses are safely built on stilts, actually over the sea. I'm not sure the reasons for this, maybe its because the island becomes very steep, very quickly, and its hard to find a flat piece of land. Maybe its simply so that the toilet at the end of the jetty isn't too far away.

Besides, being a predominantly a fishing community, you have to live by the sea.

We travelled along the coast, past the wooden homes, some of which were brand new, standing proudly next to the remains of the previous home that was destroyed by a hurricane last year: wooden sticks pointing blackly out of the sea, collapsed roofs, and slumped porches. Then through a mangrove channel and past a river taxi: one of the large wooden canoes (dories) powered by lawnmower engines and driven by entrepenurial locals. Then around to the house: a large, wooden, but very homely and cosy hut on stilts.

Christmas was great to spend with the kids. Not much to do at the house, except gaze out across the crystal blue sea, at the beach on the other side of the bight; at the other houses in the village; and at boats chugging or speeding past. But not many. It is quiet here, incredibly quiet.

At night the stars are as bright as they can be, even though the island has electricity. Everywhere you go you can see the masses of posts and cables lining the sides of the roads. The power goes almost everywhere, except right at the far end of the island, a few miles away, where people still live pretty much as they used to a hundred years ago. Our host helped provide the power to the island: he supervised the planting of the posts and the rigging of the wires. He had an almost mystical connection with the system: sometimes at night he would wake up, knowing that something was wrong at the power station, turn on a light, and then watch it die. Then he would get in the boat, speed over to the road, then drive to the power station to fix it.

Last year they got a telephone too.

If you try, its not too difficult to imagine what life looked like without electricity; or at least what it looked like here. It can be incredibly dark. Often the moon provides the only light, and on a moonless night you can't see your hand in front of your face. But not now. Dim house-lights line the shore, and at this time of year people decorate their houses with astonishing Christmas-light displays. Electronic ice crystals hang from the roofs and around the windows; and flashing fairy-lights festoon palm trees and gardens, transforming a shambling town by day into Disneyland at night. The air is thick with the smell, smoke and sounds of firecrackers, people shouting, and a boat chugs slowly past, with a gospel choir on board singing 'Go Tell it on the Mountain' with lots of passion, all through Christmas night.

But the power supply isn't perfect: it has its surges and ups and downs, though never down for long. But sensitive equipment needs protecting from these fluctuations.

I spent Christmas morning nailing pieces of wood around a butane cylinder to make it secure, so that we could eat a Christmas dinner. I have no idea how far that cylinder had come to get here. Then, after we opened our presents, I helped set up the computer with the intention of connecting it to the Internet. It wasn't quite what I had in mind for Christmas day, but it was nice to be able to help out and pay back some of the hospitality. We unpacked the multimedia computer: it came with an Interrupted Power Supply, monitor, mouse, keyboard and modem. Since the power on the island fluctuates, every PC supplied is always coupled with an IPS. This ensures that any spikes in the voltage don’t affect the running of the computer.

We plugged all the various peripherals. This was interesting. The guy who supplied the equipment had supplied only one power lead. When you live miles away from shops in the nearest town you learn to improvise; so we cut one of the other cables open, then had to fashion a plug by cannibalising the plug and cable from a hairdryer. Success. Finally we connected the modem. Everything worked, except for the modem: the door to the rest of the world.

We checked the phone line by plugging a phone into it. That was OK. We checked that the modem was seen by the software, and by the software configuration. That was OK. But no dial tone. It seemed that we weren’t going to get the machine connected on Christmas day after all, which was depressing after having triumphed over the disappointment with the power cable. But then we checked the sockets at the back of the computer. Sure enough, as is often the case, we had plugged one of the modem cables into the wrong place. We plugged in the modem correctly this time and we were online. We sent a few emails, and had a quick surf of the web. Eyes widen as the Yahoo search engine returned pages and pages of information and images about the Boer War, from all over the world.

The kids now can potentially learn so much from the web, they will see sights from other parts of the world they would never have seen before, they can read stories, draw pictures, send emails to their granny in the UK, and look at maps: all there in two-dimensions on the screen.

Outside, snorkelling the coral reef we swim in a three-dimensional world; among parrot fish, cuttle fish, zebra fish, and barracuda; amid the breath-taking coral architecture, sea weed and jelly fish. All there in incredible colour and age: coral takes one year to grow a square centimetre, and there are acres and acres of reef here.

Its the contradictions that strike me the most. A very basic house, without running water, with a pretty untrustworthy phone-line, on a remote island in the Caribbean that now has internet access. Which is, after all, only information. It's not practical in itself: it doesn't do anything other than present facts (some of dubious accuracy). It won't build houses or water pipes for you. It won't lay power lines, or catch fish. It might tell you a hundred different ways in which you might be able to do these things for yourself. Who knows what opportunities this will bring to the kids in the house? Will it make them more restless than they already are? Will it educate, inform and improve their lives and the lives of the community there, or will it send them away from the island to the mainland? But at the moment they don't even have running water, and I would have thought that clean water should come before the information highway or before TV for that matter... but then purifying water isn't half as interesting as playing on a world-connected computer, with infinite possibilities.

But perhaps I’m just seeing all this through western eyes.

It seems strangely ironic to me too, that it is 'backpacker' tourists who have really brought the internet here, travelling light and cheaply so that you can avoid the tours, and get close to the actual local culture. Backpackers brought internet cafes, which then spawned computer shops, which then lead to supplying houses with the internet-connected PC's which dramatically change everything.

But the locals don't see it that way. They see it as a replacement to TV I think, or at least an addition to it, and a way to send messages to granny in the UK. We have the privilege of having been through the whole development of the technology; but the islanders here are making a huge leap; missing out on an existing infrastructure: the mistakes, the successes, and the pollution that a developing technology produces. Maybe having no IT infrastructure inhibits their ability to make good use of the technology.

To some a wired island seems a paradise. You can now sit on a beach, anywhere in the world, with white sand all around, palm trees, go windsurfing or snorkel the coral in the morning, then connect through a modem to work in the afternoon, without ever leaving your sun lounger.

Real Estate is big business here. It seems a few people bought up land a few years ago as quick as they could, and now sell it for a big profit. A couple of individuals have cornered this market locally. They now live in the biggest houses with the best views, or in the best resort. By contrast, just down the road is a Spanish shanty town: kids play around in the dust by the side of the road; drunks stumble around or sleep at noon; and tired women put washing out to dry in the dust of the day.

On the way back, after the Millenium turn over, the news in the region is full of stories from Argentina: another developing country. Since there have been so few worldwide Y2K problems, they feel cheated: they spent a huge amount of money that they could barely afford, fixing something that turned out not to be a problem, and they are not the only people in the region who feel that way. Would that money have been better spent elsewhere? or is it simply a good thing that they now have up to date computer systems, despite the update having been unnecessary?

So that was Christmas 1999. The brave new Millenium promises more gadgets and scientific toys, more information, more and more of everything, and the poorest countries of the developing world will have to make greater and greater leaps to make to try to stay afloat. Will web-connected computers help them to achieve that? Or will it simply be an expensive fad, that ends up collecting dust and cockroaches, rusting in the corner for more important and immediate concerns such as collecting water, or farming the land in that basic fight for survival?

Author Details

| Eddie Young Network Officer UKOLN University of Bath Email: e.young@ukoln.ac.uk |