Publish and Cherish With Non-proprietary Peer Review Systems

Now that publications are increasingly being enriched with databases and audio-visual elements, the need for non-proprietary review systems – that is, peer review systems that do not require the assignment of copyright to the organiser of the peer review i.e. the publisher - is becoming ever-more pressing. Although there is a steadily growing number of peer-reviewed Open Access journals [1] and an active Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association [2], the supply fails to keep pace with the demand. More and more research funders require open access to the publications that result from research they have financed. Recently the European Commission conducted a pilot initiative on open access to peer-reviewed articles in FP7 [3], its Seventh Research Framework Programme, that may result in 100,000 reviewed articles. In so far as authors cannot all publish in Open Access journals, the EC and, for that matter, other Open Access-mandating funders impose unfair conditions on authors.

With a shift from proprietary to non-proprietary systems of peer review, initial experience has now been garnered from SCOAP [4] and the Springer experiments [5] at UKB, MPG, Göttingen University and, lately, California University [6]). This conversion can be speeded up if disciplinary communities, universities, and research funders actively enter the market of the peer review organisers by calling for tenders and inviting publishers to submit proposals for a non-proprietary design of the peer review process. Given the current situation – with the American legislature and the European Commission having clearly taken a stand in favour of Open Access – one can expect that such tenders will certainly produce interesting proposals. The time is ripe!

This article examines the idea of the European Commission putting out such a tender.

Open Access in a Nutshell

Open Access (OA) means access to research results that are peer-reviewed, well preserved and distributed over the Internet for free reuse under the sole condition of crediting the creator. The idea of Open Access has emerged with the rise of the World Wide Web. It is widely regarded as the natural successor to the classical paper-based subscription model.

For universities and research institutes OA embodies their Corporate Social Responsibility: it is showcasing their institutional talents to society, thereby enabling people and communities to participate in knowledge-based democracies. Authors want to share their knowledge and are aware that OA generates more citations of their work thus contributing to their status and prestige; here ethical principles and self-interest may coincide. Together institutes and researchers are aware that free and prompt access to scientific information improves the efficiency of scientific discovery and becomes practically imperative for enhanced publications that are composed of various resources like research data, algorithms, audio-visuals, etc. Different access regimes to different parts of such publications would make these publications unworkable.

Open access contributes significantly to the transparency of the whole research process. It eases reproduction of research which is the ultimate quality control and guarantee against scientific fraud. At the same time it reduces unintentional duplicated research effort. Powerful tools [7] now facilitate the detection of plagiarism from open access publications and finally, good news for publishers, copyright piracy is impossible in an Open Access environment. You cannot steal oxygen from the atmosphere.

Not surprisingly, the academic community has expressed its strong support for OA on many occasions. One of the early expressions was an open letter that 35,000 academics in the biomedical disciplines sent to their publishers in 2000 [8]. One should also note the recommendation of the European University Association in March 2008 to its 800 members that 'Universities should develop institutional policies and strategies that foster the availability of their quality controlled research results for the broadest possible range of users, maximizing their visibility, accessibility and scientific impact.' At the beginning of 2007 in the space of just one month more than 20,000 people mainly from the European academic community petitioned the European Commission to 'Guarantee public access to publicly funded research results shortly after publication.' More than 500 people signed the petition on behalf of their institution. As the petition has remained open, more than 7,000 people have added their support subsequently [9].

Funders, ranging from an early bird like the Wellcome Trust [10] via Research Councils of Europe, in the UK [11] and in Germany [12] and recently followed by the American legislature [13], the Council of the European Union [14] and the European Commission, started to require Open Access to articles that resulted from the research they financed.

Glossary of Open Access Terminology

For the remainder of this article it may be helpful to acquaint oneself with some of the jargon. A manuscript that is submitted to a journal is called a pre-print. The author version that is accepted for publication goes under the term post-print. The publisher version (usually a pdf document) is often referred to as final published article.

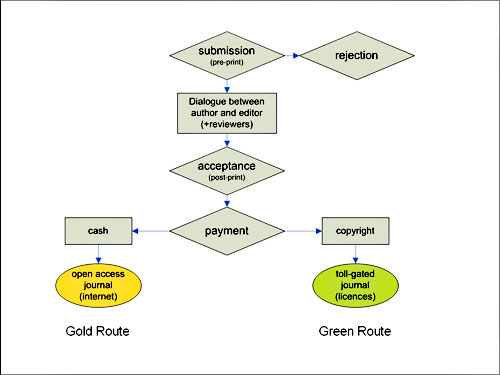

The Open Access approach to publishing is referred to as the "Gold route" and the classical publication process is labelled "Toll Gate route". Authors who try to tunnel out post-prints of their articles originally published in a classical journal to open access via institutional repositories are said to follow the 'Green route'. Authors without an institutional or subject-based repository at their disposal to post their manuscript or published article are termed 'orphan authors'.

Open Access Economics

In order to understand how Open Access publishing works compared to its classical variant, we might do worse than take a brief look at the publication process of scientific articles (Figure 1). The quality control in both approaches is identical: a pre-print goes through an editorial and peer review process that, often after revision of the manuscript, may result in a post-print. Then, before proceeding to publication of the article, publishers expect to be remunerated for their work, namely the organisation of the quality control and subsequent dissemination of the article via one of their, sometimes highly branded, journals. At this juncture, the two approaches bifurcate. In the classical approach publishers require exclusive, complete and irreversible assignment of copyright which gives them control over access to the article. Subsequently, they transubstantiate this control into revenue via subscriptions, licences, copyright clearance fees and various conditions of reuse. Conversely, Open Access publishers require a sum of money upfront, the so-called 'publication fee' or 'author fee'. Upon its receipt, they publish the article promptly in an open access Internet journal where the sole condition of reuse is the correct attribution of the content to its author(s).

Figure 1: Overview of publishing process: The Gold Route vs the Green Route

A relative cost comparison between the two approaches is quite straightforward as the only difference lies in the distribution process. The classical approach, with its complicated licensing or subscribing and content-shielding process suffers considerably in the comparison. Although publishers are rather secretive with their business data, various studies have estimated the costs of this distribution layer amounting to between 20% and 30% of the whole publication cycle. Consequently, Open Access publishing can be carried out at considerably lower cost. This, however, does not automatically mean that all institutions will benefit equally from a transfer to Open Access because the basis for pricing is different across the two approaches. In the classical model, subscriptions or licences provide the basis for pricing whereas in the Open Access approach it is the published articles themselves. As a result, a typical educational institution with a large collection of journals but which publishes relatively few articles of its own will pay substantially less in an Open Access world. Conversely, a research-intensive institution generating numerous published papers may pay more. Box 1 illustrates two examples of HE institutions in the Netherlands.

Some explanation of these examples may be useful.

- Both libraries operate a different average publication fee per article: €2000 (ISS) resp. €1300 (UU). The Web site of BioMed Central offers a comprehensive price list [15] which may provide a basis for these estimates. In their study John Houghton, Charles Oppenheim et al. estimate the average cost per article at £1524 ([16] p. XV) but mention that fewer than 50% of OA journals charge author fees ([16] p. 77). This would reduce the effective average publication fee to about £750. In this light, some further price analysis might prove useful.

- As expected, OA is very beneficial to the Institute of Social Studies, not only price-wise but also because its alumni, once back home, will keep free access to the publications of their alma mater. The somewhat more nuanced outcome for the University of Utrecht is even more surprising. If external research funders are prepared to include the cost of article publication fees in project funding (as more and more funders now do) then even Utrecht will be better off in an OA environment.

A more far-reaching exploration has been conducted of both the costs and benefits across the alternative publication models. This has now been carried out on a national scale by John Houghton and his colleagues in respect of Australia (September 2006) and the UK (January 2009) [16]. Similar studies for the Netherlands and Denmark are anticipated. The results are impressive and conclude that there exist substantial OA benefits for practically all stakeholders involved ([16] pp. XXII – XXV).

Cost Comparison: Open Access v. Subscriptions at Utrecht University

Established in 1636, today Utrecht University is an internationally renowned top research university with almost 30, 000 students and over 8, 500 staff. Annually UU publishes 5000 articles in peer-reviewed journals; of these 1500 result from externally funded research (figures 2005). Utrecht University is a signatory of the Berlin Declaration on Open Access.

Open Access | Subscriptions | ||

| Publication fees UU1 | €6,500,000 | Subscriptions and licences | €4,500,000 |

| Document supply 3 + copyright clearance fees + collection management 4 | €1,000,000 | ||

€6,500,000 | €5,500,000 | ||

| Publication fees research funders 2 | - €1,950,000 | ||

| Remaining costs UU | €4,550,000 | ||

1. 5000 peer-reviewed articles @ €1,300

2. 1500 peer-reviewed articles @ €1,300

3. Includes out of pocket costs to third parties (other libraries, publishers) and in-house handling costs.

4.Includes defining the collection, acquisitions and administration, shielding access and copyright issues.

September 2008

Bas Savenije

University Librarian of Utrecht University

Cost Comparison: Open Access v. Subscriptions at the Institute of Social Studies, The Hague

Established in 1952, the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague is an international graduate school with typically 400 students per year. Its research programme results in books, reports and about 60 articles in peer-reviewed journals annually. An intangible open access advantage is the free access that ISS alumni, who are often based in developing countries, will have to these articles.

Open Access | Subscriptions | ||

| Publication fees ISS 1 | €120,000 | Subscriptions and licences | €180,000 |

| Document supply 3 + copyright clearance fees | €65,000 | ||

| Platform or aggregation costs 2 | €25,000 | Collection management 4 | €60,000 |

€145,000 | €305,000 | ||

1. 60 peer-reviewed articles @ €2,000. The publication fee is an estimate based on the pricelist published by BioMedCentral. The list refers mainly to STM journals [17]. For social sciences the fees may be lower.

2. ISS assumes that even in a full open access world still some aggregation or platform fees will be needed.

3. Includes out of pocket costs to third parties (other libraries, publishers) and in-house handling costs.

4.This is a rough estimate. Includes defining the collection, acquisitions and administration, shielding access and copyright issues.

September 2008

Michel Wesseling,

Head of the Office of Library and Information Technology Services

Box 1: Comparison of costs with Open Access and Subscription approaches at two Dutch institutions

Open Access Mandates

Several research funders and also some universities require open access to the publications of the research they fund. A typical example is the European Commission with their Open Access Pilot in the Seventh Research Framework Programme F7 [18]. FP7 is the Commisson's €50 billion research programme, running from 2007 to 2013. The Pilot covers approximately 20% of the budget and applies to the following areas: Energy, Environment, Health, ICT, e-Infrastructures, Science in Society, Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities. The Commission requires Open Access to all peer-reviewed articles resulting from research in these areas within six or twelve months of publication. If we estimate that every €100,000 of research funding results in one peer-reviewed article, the FP7 pilot will provide open access to something like 100,000 articles. All articles must be deposited into institutional or subject-based repositories.

In order to enable authors to meet these publishing requirements, the Commission reimburses the publication fee for articles published in Open Access journals. The Commission has also tendered for the provision of a pan-European repository [19] where authors who do not have an institutional or subject-based repository at their disposal can store their article.

Currently, Open Access journals represent some 15% of the market of scientific and scholarly publishing. Statistically, this means that 15,000 articles of the FP7 pilot meet the requirements of the Commission. As copyright owners, their authors can deposit these articles in a repository immediately upon their publication.

The remaining 85,000 articles still have to be published in a subscription-based journal which includes assigment of copyright to the publisher. For these articles the authors "should make their best efforts to negotiate copyright and licensing conditions that comply with the open access pilot in FP7" [20] says the Commission in its leaflet. Authors can discover exactly what this means from the RoMeo/SHERPA Web site [21]. The site gives an overview of more than 500 classical model publishers and what they permit authors to do with their articles. About 30% permit the depositing of both pre-prints and post-prints in a repository; 21% allow the depositing of post-prints only while 12% permit the depositing of pre-prints only. The remaining 37% do not authorise anything. Unfortunately this is not the whole story. Publishers employ different embargo periods when it comes to allowing open access to these manuscripts; they vary from zero (i.e. immediate release) to four years. Moreover, the reuse conditions of these manuscripts differ widely. Some may only be displayed on the author's Web site, others solely on the institutional Web site, others yet again may not be reused in any commercial setting, etc. As some publishers apply different copyright policies to different journals, there are actually more copyright policies than there are publishers! For authors this is a labyrinth. Nonetheless, the Commission - as well as other pro-Open Access funders – wants authors to 'make their best efforts to negotiate copyright and licensing conditions that comply with the open access pilot in FP7.' And even if these authors succeed in such best efforts, open circulation will only apply to their manuscripts, not the final published article. But in citation indexes like Web of Science and Scopus only citations of final published articles are ever counted.

The Open Access requirements of the EC, and of other funders for that matter, must be regarded as unfair in respect of the 85% of authors who cannot publish in an Open Access journal.

Non-proprietary Peer Review Systems

Moreover such requirements are unnecessary.

One of the standard mechanisms for the EC to realise its policies is putting out tenders and calls for bids or proposals. Indeed, the Commission has tendered the provision of a pan-European repository for orphan authors in FP7 [22]. But lacking an appropriate peer review system, the Commission sends authors off to find their way around the RoMeo/SHERPA labyrinth. Instead, it could have tendered for bids to establish adequate non-proprietary review systems. Such a measure would follow up the policy advice of the important Study on the Economic and Technical Evolution of the Scientific Publication Markets of Europe [23] which it published three years ago. The wording of such an invitation to tender (ITT) might run as follows:

"The European FP7 Programme (€50 billion, 2007-2013) will generate a stream of published research. For seven areas of research the Commission requires that such published research appears as openly accessible peer-reviewed articles. In order to have appropriate review procedures in place to process these articles, the Commission plans to tender the reviewing process under the following conditions:

- The reviewing process must be independent, rigorous and swift.

- The reviewing may be anonymous, named or open (to be negotiated).

- As a result of the reviewing process, articles will be marked 1 to 5.

- For articles marked 3 to 5 adequate Open Access publication platforms must be available (e.g. new Open Access journals). Alternatively, authors may publish their articles in any existing OA journal.

- Upon publication all articles will be deposited in a certified (institutional) repository.

In review procedures the Commission will weigh articles with marks 3, 4 and 5 as if they were published in journals with impact factors 1-3, 4-8 and 9-15 respectively. (These figures are nominal and subject to disciplinary calibration). A yield of at least 100,000 articles during the Programme period across the selected research areas is anticipated.

It is possible that more than one proposal will be accepted in order to cater for different disciplines. The Commission will seek the advice of EURAB/ESF/EUA/EUROHORCS/ERC in the proposal selection process."

Box 2: Wording for a possible Invitation to Tender for Non-proprietary peer review systems

The wording of the proposed ITT above requires some explanation:

- This imaginary ITT is geared to the EC but could easily be adapted to (consortia of) funders or universities alike which have developed distinct Open Access policies.

- Condition 4 above creates an adequate Open Access solution for all authors within the mandate. Of course, if authors insist on publishing their article in a Toll Gate journal (and undertake the complicated process of negotiating delayed open access to their post-print) they may still do so.

- The announcement that in review procedures articles with marks 3 to 5 will be weighed as if they were published in journals with certain impact factors aligns this approach with the existing review systems. The advice of prestigious European research authorities – all fervent Open Access advocates [24] - authorises this important step. This nuanced approach also disincentivises a costly iteration of rejection and re-submission of articles.

- Of the total of 100,000 articles, 15,000 can already be published in Open Access journals today. So there is a market for 85,000 open access articles e.g. for about 120 new Open Access journals (120 journals x 7 years x 100 articles/journal-year = 84,000 articles.)

- Proposals may include existing Open Access journals. Especially for young Open Access journals, i.e. journals that have not yet gathered a journal impact factor, this call offers the opportunity to gain accreditation by the Commission.

- Classical publishers could seize the opportunity to switch Toll Gate journals to Open Access. The expected number of articles should stimulate the Open Access market.

Conclusion

Acceptance of a proposal means that the proposed publication channel (e.g. a journal) has a non-proprietary review system in place that meets the Commission's requirements. Although the direct aim of the tender is to create a level playing field for researchers who are involved in the Open Access Pilot in FP7, any other author may equally publish via such a channel. Essentially, the outcome is a directory of accredited Open Access publication channels. The action is very scalable; other funders or (consortia of) universities can easily join in or adopt similar initiatives.

Finally, there is no risk in opting for this approach. The worst-case scenario would be that the call does not result in any accepted proposals. If that were the case, the Commission, or any other funder for that matter, need only fall back on its current position.

References

- Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) http://www.doaj.org/

- Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA) http://www.oaspa.org/

- Research - Science and Society:The European Commission launches an open access pilot in FP7

http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/index.cfm?fuseaction=public.topic&id=1680 - SCOAP3 - Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics http://scoap3.org/

- Library Journal: Springer and Max Planck together again; Michigan celebrates one million scans

http://www.libraryjournal.com/info/CA6528977.html - Library Journal: University of California Libraries, Springer Strike Open Access Deal

http://www.libraryjournal.com/article/CA6631517.html - Shambles: Plagiarism Tools http://www.shambles.net/pages/staff/ptools/

- Public Library of Science (PloS): Read the Open Letter

http://www.plos.org/support/openletter.shtml - Petition for guaranteed public access to publicly-funded research results

http://www.ec-petition.eu/ - Wellcome Trust: Position statement in support of open and unrestricted access to published research

http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/doc_WTD002766.html - Research Councils UK: Access to Research Outputs: RCUK position on issue of improved access to research outputs

http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/access/default.htm - DFG-funded Project Shows How to Make Works Accessible Free of Charge on the Internet

http://www.dfg.de/en/news/press_releases/2007/press_release_2007_23.html

Open Access at the Max Planck Society

http://open-access.net/de_en/information_on_oa_by/max_planck_society/ - An open access mandate for the NIH

http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/newsletter/01-02-08.htm#nih - Council Conclusions on scientific information in the digital age: access, dissemination and preservation

http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/intm/97236.pdf - Comparison of BioMed Central's Article Processing Charges with those of other publishers

http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/apccomparison/ - John Houghton, Charles Oppenheim et al., "Economic implications of alternative scholarly publishing models: Exploring the costs and benefits", January 2009

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/rpteconomicoapublishing.pdf - BioMed Central | for authors | Article processing charge comparison

http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/apccomparison/ - The European Commission launches an open access pilot in FP7

http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/index.cfm?fuseaction=public.topic&id=1680 - Scientific Information Repository supporting FP7

ftp://ftp.cordis.europa.eu/pub/fp7/ict/docs/e-infrastructure/20081216-infoday-morais_en.pdf - Leaflet Open Access Pilot in FP7

http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/open-access-pilot_en.pdf - Statistics for 579 publishers

http://www.sherpa.ac.uk/romeo.php?stats=yes - Info package FP7

http://cordis.europa.eu/fp7/dc/index.cfm?fuseaction=UserSite.FP7DetailsCallPage&call_id=190#infopack

Scientific Information Repository supporting FP7, presentation Carlos Morais Pires

ftp://ftp.cordis.europa.eu/pub/fp7/ict/docs/e-infrastructure/20081216-infoday-morais_en.pdf - Study on the economic and technical evolution of the scientific publication markets in Europe

http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/pdf/scientific-publication-study_en.pdf - EUROHORCs – European Heads of Research Councils - Recommendations on Open Access

http://eurohorcs.drift.senselogic.se/download/18.770467ab119dd5c597080004322/EUROHORCs'+Recommendations+on+Open+Access+200805.pdff

EURAB - European Reseach Advisory Board – Final Report

http://ec.europa.eu/research/eurab/pdf/eurab_scipub_report_recomm_dec06_en.pdf

EUA – European University Association - urges universities to develop clear strategies to advance open access http://www.eua.be/index.php?id=48&no_cache=1&tx_ttnews%5btt_news%5d=518&tx_ttnews%5bbackPid%5d=11

ERC – European Reseach Council - Scientific Council Guidelines for Open Access

http://erc.europa.eu/pdf/ScC_Guidelines_Open_Access_revised_Dec07_FINAL.pdf