Why Are Users So Useful? User Engagement and the Experience of the JISC Digitisation Programme

Do we know enough about what our users' needs are when creating online digitised scholarly resources? What are the benefits of engaging users? In what way can they be useful to the process?

These might sound like rhetorical questions, yet, looking back at the last decade of activity in digitisation and creation of online resources, such questions have been tackled by content providers only in part, and with various degrees of success. Millions of pounds of public funding have been spent in digitisation so far. However, this is still, on the whole, an activity which only pays partial attention to the users for whom the content is being digitised, and their relevant needs.

This article draws on the experience of the JISC Digitisation Programme Phase Two (2007-2009)[1] and focuses on two case studies where effective practices in user engagement have been adopted in the development of digitisation projects and consequent creation of online scholarly resources. It attempts to identify:

- key areas where user engagement has been particularly useful

- the successes and challenges of pro-actively involving users

- some practical tips on working with users in an effective way

Traditionally, much digitisation activity funded by public money in the UK under either the cultural heritage or formal education banner has been led more by supply rather then demand. The prospect of free and democratic access to high-quality digitised content over the World Wide Web has often resulted in institutions undertaking digitisation projects with the emphasis more on making the digitised content accessible online rather than carefully researching the needs of their target audiences. Nor have they always considered providing them with content and functionalities that respond to their demands. 'If you build it, they will come' has been perhaps too common a mantra, underpinned by the belief that it will be enough to publish rare or unique content on the Web in order for users to flock in and for a Web site to thrive.

However, making sure that users are embedded in the process of creation of a digitised resource is important. As recognised by the Strategic Content Alliance's [2], study Sustainability and Revenue Models for Online Academic Resources, '[t]he value of a [digitisation] project is quantified by the benefits it creates for users', which has an impact on how much a resource will be used and, in turn, its chances of survival and sustainability. A quick review of past programmes and studies reveals how researching and targeting users' needs, as well as involving users in the creation of online resources, and keeping in touch with them, was and still is a major concern faced by institutions and organisations involved in the creation of online content.

The Evaluation of the NOF digitisation programme [3, 1999-2004, the most substantial UK Government investment in digitisation to date, concluded that:

'The identification of target users by the majority of projects was not policy-led or particularly consistent with the aim [of the programme] [...] Target user groups in the majority of projects were not selected according to any particular lifelong learning criteria.' (p. 8)

Although an objective study of the long-term usage and impact of the NOF programme has not taken place, one might hazard that, with some notable exceptions (Vision of Britain, Am Baile, The Old Bailey [4] to name just a few projects), a lot of the content produced under this nonetheless pioneering programme now seems little known, used or updated [5].

If a lack of focus and depth of knowledge in identifying users and users' needs mainly within the cultural heritage sector targeting 'lifelong learning' characterised many of the NOF digitisation projects [6], the 2005 report Digitised Content in the UK Research Library and Archives Sector [7] also highlighted the lack, within the Higher Education sector, of an 'overview of user needs and demands for digitised content in the UK'.

While the two reports above emphasised the problems of targeting relevant users and knowing about their specific requirements, the 2006 report LAIRAH project: log analysis of Internet resources in the arts and humanities [8] posed the question of what happens to digital resources after completion, based on the anecdotal evidence that some of the resources became well known but others were quickly forgotten. The LAIRAH team estimated that between 30-35% of resources created through public funding remain unused. It is interesting to note that when one looks at the various reasons for their non-use, 'user contact' is one of the determining factors in the success of a resource:

'Few projects carried out formal user testing, thus have little idea of the needs of their user community. Those projects which had carried out user tests were amongst the most well used in our survey.' ([8], p. 6) [...] PARIP carried out a user needs survey at the beginning of the project, and the Channel Tunnel project conducted focus groups. These are both examples of especially good practice: their creators were aware of the needs of their users and could take design decisions accordingly from very early in the project.' (p. 28)

And finally, moving from project to institutional level, the results of the 2008 survey entitled JISC survey of Head and Senior Librarians in HE and FE [9] still revealed that only 41% of Higher Education institutions have made use of some user consultation to determine priority collections to digitise.

The JISC Digitisation Programme Phase Two (2007-2009)

The JISC Digitisation Programme Phase Two, totalling an investment of £12m, started in March 2007 and came to an end in Spring 2009, when 16 new digital collections went live, spanning centuries of UK and international life, culture and history, and including resources as varied as pamphlets, newspapers, cabinet papers, poetry manuscripts, theatre ephemera, political cartoons, radio and TV programmes, maps, images of art works and thesis. The programme built on the JISC Digitisation Programme Phase One (2004-2006), worth £10m, which delivered 6 projects, ranging from medical journals' backfiles, to parliamentary papers, newspapers, sound recordings and population data.

In line with the JISC Digitisation Strategy [10], this large-scale digitisation programme placed a strong emphasis on the creation of digital collections which would be 'Driven by learning, teaching and/or research requirements and where clear evidence of user needs has been identified' [11]. At the bidding stage, projects were asked to document audience analysis activities they had carried out, consultation with experts in the selection of relevant material and how the content selected mapped to the needs of identified courses or research priorities.

Some examples of how this work was carried out by two of the projects funded by the programme (Archival Sound Recordings and the John Johnson Collection [12]) are documented on the Strategic Content Alliance's document The Guide to Researching Audiences. Case Studies [13].

Recognising that users are co-producers of a resource's value, to the extent that its value is determined by how much a resource is used, the best projects have approached user engagement as a lifecycle process taking place before, during and after the creation of a digital resource and informed by a strategic approach including a range of activities aimed at soliciting users' input in a two-way exchange, where users shape, at various points and in various degrees, the development and creation of a digital resource.

The level of user engagement activities carried out by the 16 projects was generally high. What follows are examples of some of the key areas where interaction with users has been most useful that have emerged from the case studies of two digitisation projects:

- The British Library's Archival Sound Recording 2 (ASR2) [14] – over 25,000 recordings of music, spoken word, and human and natural environments

- Oxford University's First World War Poetry Digital Archive (WW1PDA) [15]– over 7000 items of text, images, audio and video material on key First World War poets

Figure 1: Screenshot of the Archival Sound Recordings home page [16]

Figure 2: Screenshot of the First World War Poetry Digital Archive home page [17]

Conducting Effective User Engagement: A Starter for Ten

Below I have detailed ten possible steps towards more effective engagement with the beneficiaries of a project.

1. Recognising the Importance of User Engagement

The first step for conducting effective user engagement is to recognise the importance of this activity in the development of a project and then task somebody with the responsibility of carrying it out, often as a specific work package that operates across all the other activities of project work.

The way in which this role is established within a project team might follow different models, each with their own pros and cons, such as creating an ad hoc position or absorbing the tasks within existing team members.

The need for the specific post of Engagement Officer was identified in the first phase of the ASR2 Project (this project was also funded in Phase One of the JISC Digitisation programme). Outcomes of workshops and user panels in the first phase of the project highlighted how the academic community was still a bit baffled by audio resources, not quite knowing how to incorporate them within teaching and research. The team therefore felt that a more targeted engagement with the user community was needed in order to encourage take-up.

The Engagement Officer worked to a very specific brief that was developed as part of the project's marketing and communication strategy, and which included a wide range of activities, such as:

'the development of an online user network, a series of case studies, a monthly newsletter to HE/FE institutions, a project blog and attendance to a large number of conferences, workshops and engagement with online interactions.'[18]

She also worked in close collaboration with the project's User Panel recruited through a one-day event at the British Library.

2. Establishing a 'Relationship' with Users and Sustaining It

Users are not a homogenous and anonymous entity, they are 'individuals' and as such need to feel appreciated. As projects found, it is beneficial to set up a 'relationship' with user groups from the beginning of a project (and before the project, to find out about potential needs), and nurture it throughout in an iterative fashion. For the Project Manager of the WW1PDA: 'To ensure a usable and popular resource, engagement with users was at the heart of the project.'[19]

The WW1PDA employed a typology of users to provide input into the different areas of the project. A steering group consisting of key experts in the field of First World War Literature was recruited to advise on what should be digitised, the metadata that should be captured and system requirements. One of the unexpected, but very useful, contributions made by specialist researchers was their request to participate in the Quality Assurance process, by viewing all the digitised manuscripts online. By doing so, they also carried out usability testing, thus providing valuable feedback on the various functionalities offered by the Web site. To develop the Education section, the team consulted secondary schools and Higher Education teachers of First World War literature and history through a number of Teaching WW1 Literature workshops. The workshops proved extremely useful in finding out more about the teaching of the subject itself and teachers' needs without emphasising the technology as such (see step 4 below).

The challenge of sustaining the relationship throughout the project was met by keeping in regular contact by email, telephone or one-to-one meetings, for help on very specific tasks, such as the Quality Assurance process mentioned above, or by visiting archives with project staff to select manuscript material.

This project was also particularly skilful in exploiting Web 2.0 techniques and networks of users to maintain a relationship with users beyond the duration of the project and to promote the resource. They created wikipedia entries about relevant WW1 poets, established a blog and Twitter feed to communicate latest news, set up Google discussion groups, built a Facebook group and fan page, a Flickr account, and produced podcasts that were posted on iTunes , iTunesU and YouTube.

Did the Web 2.0 techniques pay off? It may still be too early to judge, but the project noticed that, for example, the bounce rate of visitors to the site had substantially decreased for those users coming from these Web 2.0 initiatives, thereby suggesting that they were users particularly interested in the resource, rather than users who had come across it through a generic Google search and realised it was not what they were looking for.

3. Knowing What to Do with Users' Feedback

Usability testing is a great way to find out how potential users react to a new digital resource, its content and functionalities. Whether it is carried out by an external professional company or in-house, some of the challenges encountered by projects highlighted the importance of knowing how to pose the right questions to users and deciding how to interpret users' feedback, and act on it.

The ASR2 project team had identified the need for more user interaction on the Web site, and explored with its users' panel the introduction of Web 2.0 features such as adding tags, comments and ratings to audio clips. At first, however, it met with hostility from their users' group which was disturbed by the possibility that users might undermine the authority of the 'archivist's record'. The users' group was also concerned about the differing criteria users might adopt for rating recordings; some group members pointed out that if 'quality' of a recording was adopted as a criterium, an old audio clip might not score highly, even though its content might still be very valuable. Such anxieties, however, were assuaged when the team proposed that users' comments would be clearly displayed as distinct from the archivist's documentation and the Web site made clear the type of comments that were being solicited (i.e. information about the recording, rather than personal likes or dislikes). Moreover, it was decided to substitute the audio clip 'rating' with a 'Favourite' functionality.

Usability testing was also extremely useful in impproving the presentation of the home page. Some of the testers' comments, such as, 'It seems to be fairly limited and it doesn't give you an idea of what is here...'[20] revealed that users did not appear to read the opening paragraph on the home page describing the scope and content of the digitised collections. A new version of the home page included a punchier, bullet-point style opening paragraph with clear information on the content of the Web site and what the different categories of users were allowed to do.

4. Embedding Resources into Teaching and Research

Getting new resources, which will be competing with existing ones, embedded into teaching and research is one of the biggest challenges highlighted by projects. Not only is it the case that take-up within teaching courses or research activity is something that develops over time, but it is important that a resource be embedded in the academic practice of its users.

The approach adopted by the WW1PDA Project towards the organisation of the Teaching WW1 Literature workshops quite deliberately fought shy of the technology, instead asking teachers what functionality they would like to see on a Web site. In effect, they focused on finding out 'what constituted the effective teaching and study of this area,' and examined the 'learning objectives of existing courses'. Discussions were recorded throughout the day and revealed, perhaps in a more indirect way, how these users

'...wished to both discover and visualise content for educational purposes, for instance browsing via keywords associated with the National Curriculum, hyper-linked metadata, purpose built resource packs to teach particular topics, and being able to present a selection of items with additional notes to students...' [21]

The team then elaborated the findings and came up with ideas for how these needs could be best addressed by the technology available.

During the workshops, teachers were also asked to author a number of learning resources to upload on the Web site (resource packs, Powerpoint presentations or collections assembled through the Path creation tool [22]).

Figure 3: Pathway on the Western Front [23]

Although various resources were created, the team realised it had been too ambitious in what it had asked teachers to contribute. It is therefore planning to re-focus future workshops, concentrating on the creation of just one type of learning resource.

Early evidence of take-up suggests that some teachers have used this collection in the classroom as part of creating a wiki on WW1 poetry – 'students have been using the archive for research and will be linking to it' – and a number of teachers commented how 'It's very good to be able to refer students to a web site of such quality from a sound academic source'. [24]

5. Galvanising Users as Project Advocates

Once even a small group of key users have bought into the new resource, there is a lot they can do as volunteers to advocate its value within their network of contacts. Knowing that dealing with sound recordings constituted a challenge for potential users, as many in the education sector are still not familiar with using this format, the ASR2 project team asked members of their users panel to develop case studies and testimonials to show how they had used the recordings in a teaching, learning and research context and had these case studies ready for when the new collection was launched. It was more difficult to approach users beyond members of the users' panel, but the project partly managed to do this by tracking down users from Web logs, identifying which institutions were accessing the resource more heavily and contacting the Librarian.

This generated a number of case studies and testimonials from lecturers, PhD students, researchers and librarians, including an FE teacher commenting on using the Art and Design interviews for a project on famous photographers:

'The realism of it [interviews with photographers] inspired students and encouraged them to source other material beyond Google searches. It also placed the photographs in context, which you don't get from Google.' [25]

The Project Manager acknowledged the difficulty of measuring the impact that the case studies might be having - whether other teachers and researchers were being inspired by them and used the collection more. However, she felt that developing them was important for various reasons, namely: to show how sound resources could be used in teaching and research; to build up a case for the resource; as advocacy; proof of value; and as part of a strategic approach to justify the resource's value and making a case for its sustainability within the hosting institution.

6. Getting Users to Create Content

Debates on the usefulness of Web 2.0 tools and techniques when it comes to user generated content within the realm of digitised scholarly resources are still hot, with supporters hailing the potential for harnessing the wisdom of the crowd and detractors alarmed by the risk of undermining the authority and trust of a scholarly resource. [26]

However, there are plenty of examples now of how, if well organised and focused, setting up a process for users to contribute content to a scholarly Web site can return surprising results.

As part of their digitisation project, the WW1PDA set up the Great War Archive [27], a section of the Web site where the general public was asked to submit digitised items relating to the First World War in their possession. Surpassing initial estimates, the project received more that 6,000 submissions in the span of just a few months, and subsequently had to create a Flickr group to accommodate more material coming in from the public. Submissions included:

...diaries from Gallipoli, love letters from France, audio interviews with veterans, signals sent on Armistice, and a bullet dented tea tin that saved a soldier's life.[28]

The initiative not only provided new context to the digitised poetry manuscripts, but also experimented with a new model of public engagement in a university project involving mass amateur digitisation. A lot of thought and effort, however, went into its organisation. First the team had to define target groups for the Great War Archive, then build the interface for the collection, catalogue and approve of items, market the initiative, organise 'submission events' in libraries where staff would help the public to digitise and upload its material, and finally migrate all the items and metadata to the Web site's content management system.

If unprepared for the level of response received from the public, the project was able to cope by diverting internal resources, by employing extra staff to help process the non-digitised material received through the post, and by extending the initial submission deadline.

A definite lesson from the project was the need to put in place robust processes and mechanisms to cope with any unanticipated degree of success.

7. Targeting Dissemination Activities

The majority of projects certainly employed all the more traditional marketing and PR activities to publicise their resource, such as press releases, mailings, leaflets and launches. However, what worked best in most cases were dissemination activities with a focus on reaching key audiences, either through existing networks or 'places' where these communities were already likely to be found.

The ASR2 Project, for example, found that publicising its Holocaust collection through mailings to specific subject groups, such as Higher Education History, Jewish and Theology Studies networks, was particularly successful, returning a number of articles in the press as well as online newsletters and blogs.

Figure 4: Holocaust Survivors Collection [29]

While generic calls for case studies and competitions on the project's Web site failed to attract many responses, the project's Newsletter proved very popular. In the words of the Project Manager, this demonstrated that 'people are interested in collections that may be of value to them, but are not generally willing to spend time on additional activities.' [30]

This echoes the project's experience of setting up a Facebook page, where activity soon died out after an initial spurt of subscriptions, pointing to the fact that 'busy academics (and students) are interested in using resources, but not spending time speaking about them.' [31]

The ASR2 also found that one of the main challenges was how to ensure that information about the project cascaded down to primary users (eg students) from the 'intermediaries' (librarians, teachers, etc) they had principally targeted. The project felt that other tactics could be employed to complement those going via intermediaries, such as having posters of the collections in the library and doing road shows. The project also recognised the benefit of bundling their new 'product' with existing ones offered by their host institution in order to increase their value proposition.

8. Demonstrating Value and Impact ...

The degree to which users perceive the value of a resource will be reflected in its usage and the impact a resource has upon its users. A recent report commissioned by the Strategic Content Alliance, points out how:

Digital resources do not exist in a vacuum – sustaining them requires that project leaders understand the unique value that a resource provides and where it fits within the competitive landscape. What does a resource contribute that sets it apart? Is its content rare or unique [...]? Does the resource provide important services or functionality that can be found nowhere else? [32]

In the case of these projects, not only is the content unique but both have included features on their Web sites that add value to the digitised content – and users have been vital in the identification of such features.

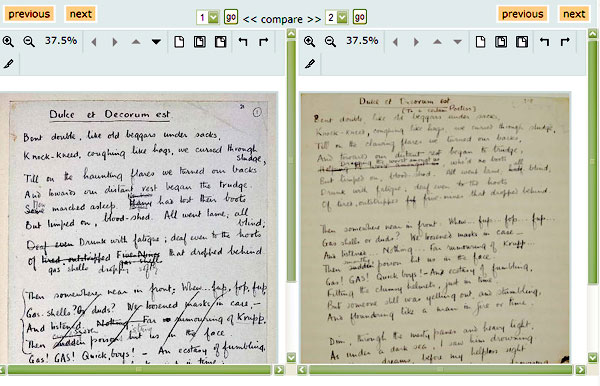

In their consultation with the steering group, the WW1PDA found out that one of the most common problems that researchers had was how to compare different versions of manuscripts of the same poem residing in different archives. The project addressed this need by creating a functionality on the Web site that displayed manuscripts side-by-side. In the same way, when speaking to teachers, it emerged that some of them may not have Internet access in the classroom. Therefore, downloadable resource packs mainly comprising Powerpoint presentations were also developed alongside Web-based functionalities.

Figure 5: Manuscript comparison tool [33]

It is still too early for the digitisation projects funded by JISC to determine how much impact they are having on users – although JISC has carried out a study, the Usage and Impact Study of Phase One Digitisation Projects. [34] However, as with the choice of dissemination activities, sustaining the community of users that has been created during a project is vital as an eventual means of measuring the impact a resource has on its target audiences.

A recent JISC-funded study developed a toolkit, the Toolkit for the impact of digitised scholarly resources [35] which suggests a range of methodologies to employ to track usage and impact. These methodologies will be much more effective if a project has easy access to its community of users, and it is worth bearing them in mind when designing a Web site.

9. ...and Making a Case for Sustainability

Inevitably, especially once project funding has come to an end, an institution may be faced with having to sustain a newly created digital resource. If it can demonstrate that it is being used and is having an impact on its community of users, this will go a long way to making a case for more investment. This will apply as much internally, to the hosting organisation, as externally, to a potential partner or funder.

The WW1PDA has been running under different guises since 1996. Its continued success has been determined by a number of factors. They are: institutional support from the University of Oxford; and the commitment of a project champion within the University; but also the fact that the project has been able to: keep in regular contact with its key users; respond to their changing needs; and make a case for continuous support both to their hosting institution as well as external funders.

The project's Final Report to JISC details how the archive was first conceived and its developments over the next ten years:

'Between 1996-98, under the JISC Technology Applications Programme [...], Oxford University developed the "Virtual Seminars for Teaching Literature", based around a multimedia archive holding digital collections relating to the poet Wilfred Owen. Considered pioneering at the time this archive has been one of the major influences on the use of IT in research and teaching within the humanities, and has been regularly cited in publications [...]. It won several awards [...] and was used by several national bodies [...] as a demonstration of excellence.

[...]

In consultative exercises held with users of the existing resource, at workshops, and through direct feedback, it was indicated that expansion of the collection was the primary demand. [36]

Based on strong evidence of users' needs, the University of Oxford applied for funding for what became the WW1PDA and subsequently received an additional grant to further develop interactive functionalities on the Web site.

10. 'Listen to your users, but don't be bullied by them'

This is a quote I stole from Susan Whitfield, Project Manager of the International Dunhuang Project (IDP) [37] at the British Library, in her presentation on what makes a digital resource a well-used resource, at the JISC Digital Content Conference 2009, when she was asked about her top tips. [38]

Susan was referring to a couple of issues here. First, the challenge of ever knowing what users really want, how to cope with 'unexpected uses' of a resource and the fact that the majority of user consultation is still only representative of a sample of users, and therefore partial. Secondly, and most importantly, as a consequence, the need for a project to keep focused on its own vision and the needs of key categories of heavy primary users, as the JISC projects also found; rather than trying to satisfy the needs of too many different types of users, which inevitably runs the risk of building a resource for everybody and nobody.

Conclusions

These are the main areas that have emerged as the ones where 'user engagement' can prove most useful in increasing the use and value of a digital resource. Other projects may have identified other areas, and some of them can be considered rather 'common-sense'. The fact is though, that, when a team is involved in a large-scale digitisation project, very often the 'digitisation' element of the project, because of its demanding technical nature, tends to absorb most of a team's attention, and the creation of the final Web site delivering the content tends to come as an after-thought.

It is hoped that these reflections will be of interest to new projects and that they can provide a starting point the better to document the experience of large-scale digitisation projects in their efforts to involve users in a pro-active manner when developing an online digitised scholarly resource.

References

- JISC Digitisation programme Phase Two

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/digitisation/projects.aspx - Sustainability and Revenue Models for Online Academic Resources, An Ithaka Report, Guthrie, K., Griffiths, R., and Maron, N., Strategic Content Alliance

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/themes/content/contentalliance.aspx, 2008

http://sca.jiscinvolve.org/files/2008/06/sca_ithaka_sustainability_report-final.pdf, p.6. - The Fund's ICT Content Programmes. Final evaluation report, Education for Change, March 2006

http://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/er_eval_ict_final_rep.pdf - Vision of Britain http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/index.jsp

Am Baile http://www.ambaile.org.uk/

The Old Bailey http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/ - See the New Opportunities Fund (NOF) Digitisation projects Web site created by Alastair Dunning for a breakdown of NOF projects and their current status http://web.me.com/xcia0069/nof.html

For anecdotal evidence of the lack of knowledge or use of content created under NOF, see also the Save the NOF-Digi content! petition at

http://www.petitiononline.com/savedigi/ - The Final evaluation report also highlights the difficulty of measuring impact of projects because of the lack of baseline information and that projects "had little contact with end users." (p. 9)

- Digitised Content in the UK Research Library and Archives Sector, Bültmann, B., Hardy, R., Muir, A., Wictor, C., JISC and Curl, April 2005

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/uploaded_documents/JISC-Digi-in-UK-FULL-v1-final.pdf, p4 - LAIRAH project: log analysis of Internet resources in the arts and humanities. Final Report to the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Warwick, C., Terras, M., Huntington, P., Pappa, N., Galina, I., University College London, September 2006

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/infostudies/claire-warwick/publications/LAIRAHreport.pdf - JISC survey of Head and Senior Librarians in HE and FE, JISC, 2008, p.37

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/publications/attitudinalsurvey2008librariansreport.pdf - JISC Digitisation strategy

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/jisc_digitisation_strategy_2008.doc - JISC Digitisation Programme Phase Two - Request for Proposals, p.3

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/funding/2006/05/digitisation_rfp_april_2006_final.pdf - Archival Sound Recordings http://sounds.bl.uk/;

John Johnson Collection http://johnjohnson.chadwyck.co.uk/marketing.do - The Guide to Researching Audiences. Case Studies, p.8 and p. 20

http://sca.jiscinvolve.org/files/2009/07/sca_audiences_case_studies_v1-03.pdf - Archival Sound Recordings http://sounds.bl.uk/

- First World War Poetry Digital Archive http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/

- Archival Sound Recordings http://sounds.bl.uk/

- First World War Poetry Digital Archive http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/

- Archival Sound Recordings 2 Final report, p. 7

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/asr2finalreport.pdf - First World War Poetry Digital Archive Final report, p.8

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/ww1finalreport.pdf - Archival Sound Recordings 2 Final report, p. 31

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/asr2finalreport.pdf - First World War Poetry Digital Archive Final report, p. 20

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/ww1finalreport.pdf - First World War Poetry Digital Archive, Pathways

http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/education/pathways - Pathway on The Western Front, First World War Poetry Digital Archive

http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/education/pathways/users/stuart/paths/jqrjbx/viewer/ - Quotes from teachers obtained by the Project Manager during workshops.

- Archival Sound Recordings Web site, case studies http://sounds.bl.uk/CaseStudies.aspx

- See the concerns expressed by the Re-Raphaelite resource project's Audience Research report, outlined on the JISC Digitisaton Blog,

http://digitisation.jiscinvolve.org/2008/07/07/is-academia-ready-for-web-20/ - The Great War Archive http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/gwa/

- First World War Poetry Digital Archive Final report, p. 18

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/ww1finalreport.pdf - Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, Archival Sound Recordings

http://sounds.bl.uk/View.aspx?item=021M-C0410X0030XX-0500V0.xml - Archival Sound Recordings 2 Final report

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/asr2finalreport.pdf, p20 - Archival Sound Recordings 2 Final report

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/asr2finalreport.pdf, p23 - Maron, N., L., Smith, K., K., and Loy, M., JISC (Strategic Content Alliance), July 2009, Sustaining digital resources: An on-the-ground view of projects today, Ithaka case studies in sustainability, p.14

http://sca.jiscinvolve.org/files/2009/07/sca_ithaka_sustainingdigitalresources_report.pdf - Manuscript comparison tool, First World War Poetry Digital Archive

http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/db/compare.php?CISOITEM1=1&CISOITEM2=2&TOTSELECT=3 - Usage and impact study of JISC-funded phase one digitisation projects, Oxford Internet Institute, JISC, 2009

http://microsites.oii.ox.ac.uk/tidsr/system/files/TIDSR_FinalReport_20July2009.pdf - Toolkit for the impact of digitised scholarly resources

http://microsites.oii.ox.ac.uk/tidsr/welcome - First World War Poetry Digital Archive Final report, p.4

http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/digitisation/ww1finalreport.pdf - International Dunhuang Project (IDP) http://idp.bl.uk/

- See the JISC Digitisation blog post, final lines.

http://digitisation.jiscinvolve.org/2009/07/02/jdcc09-user-engagement-users-impact-and-metrics/#more-522