Mobilising the Internet Detective

'The mobile phone is undoubtedly [a] strong driving force, a behaviour changer…Library users will soon be demanding that every interaction can take place via the cell phone' [1]

The move towards mobile technologies in libraries and in the wider educational environment is gathering increasing momentum as we enter a new decade. This is reflected in the huge amount of Web content, research reports and innovative projects devoted to mobile learning and mobile applications in libraries which can be found via a quick search on Google. This article describes our own foray at Intute into the world of mobilisation, via a JISC Rapid Innovations [2] project in 2009.

The aim of the Mobile Internet Detective Project was to adapt Intute's well respected and popular online Internet Detective tutorial [3] to develop a prototype application suitable for access on a mobile device. As well as investigating the provision of more flexible access for end-users, the project was also intended to act as a test bed to inform the potential re-development of other JISC services based at Mimas [4], (the home of Intute) and build on existing expertise in mobile technologies within the organisation.

The foundation stone for this work was a qualitative market research programme commissioned specifically for the project. This enabled us to find out directly about the needs of students in Higher Education in the UK and their own views on the use of mobile technologies for learning. The research provided invaluable insights and also sounded some notes of caution which informed our subsequent work on standards and content for mobile applications.

Why Mobile?

Confirming the influence of mobile technologies in an educational context, the 2010 edition of the New Media Consortium's Horizon Report [5] once again highlighted mobile computing as a key emerging technology likely to become mainstream for educational institutions within the next 12 months. This move towards mobile learning is also reflected elsewhere. For example the report Student Reflections on Lifelong e-Learning [6] in 2009 found that:

...students demonstrated a growing maturity in their choices of technology and their use of online tools to support their learning towards the end of their courses' and 'students used their own technologies such as mobile phones and mp3 players creatively as an integral part of learning.

Within this context, our colleagues at Mimas have already demonstrated expertise in the arena of mobile learning, with the mobile version of the Hairdressing Training service [7] one of the winners of the Handheld Learning Awards 2008.

Intute's successful bid for a JISC Rapid Innovations Grant reflected a commitment to investigate extending the reach of our services to include mobile users who, as the mobile Internet has developed, have come to expect higher standards when browsing on their handsets. Within this context, it seemed clear that the needs and behaviour of a mobile surfer differ greatly from those of a desktop surfer; so the Mobile Internet Detective Project aimed to deliver a user-friendly mobile site that was fast and inexpensive to load, providing the right content, presented in the right order and with an adapted layout.

Methodology

The Mobile Internet Detective Project was one of around 40 JISC Rapid Innovations projects in the Information Environment Programme. As the projects were headlined as Rapid Innovations, it was refreshing to see JISC adopting an innovative approach to project management and reporting, with an emphasis on building a community, sharing information and ensuring, as one of the project requirements, that code was made available as open source using a code repository for each project.

This streamlined project documentation was implemented at the outset by JISC, using Google Docs to provide information and collect participant feedback on the new approach. A particularly pleasing aspect was the requirement for projects to maintain a blog throughout the life of the project, with the added benefit of the combined posts making up the final report, with suggested headings and tags provided. Whether an update, reporting on user testing or design considerations, the tags enabled the aggregation of posts in one place, keeping the community updated easily and in a timely fashion [8].

Another JISC-inspired innovation was a two-day event held in Manchester for software developers and project representatives. The event, entitled Rapid Innovation in Development [9], was arranged to bring together the innovations projects in order to demonstrate their outputs, share ideas and also to help the delegates refine their project pitches with a view to securing more funding for further development. Overall the two days provided a series of lightning talks and 'birds of a feather' sessions on issues such as Google Android, linked data and repositories. Delegates also heard an introduction to the DevCSI [10], a new project with the aim of establishing a recognisable sector-wide community of developers.

Market Research

Engagement with users was a key aspect of the project from the start. The original Internet Detective online tutorial is aimed at helping undergraduate students to assess the academic validity of Web sites. Whilst there are many assumptions made about how students use the Internet and about preferences for mobile technology we wanted to hear the voices and opinions of student users themselves on these subjects.

Intute therefore commissioned consultants to undertake a market research programme. This took place in September 2009 in Manchester and London. In total 48 undergraduate students participated in four focus groups and four in-depth interviews. Participants were drawn from a range of red-brick and new universities, studying a wide variety of academic disciplines. The research had two main objectives:

- to provide detailed feedback on the proposed service based on student user needs;

- to determine user requirements and the technical specification for a prototype.

During the focus groups and in-depth interviews the students had access to the Internet Detective tutorial through laptops and were presented with a mock-up of the Mobile Internet Detective site.

The research revealed some fascinating detail about how students use the Internet for their academic work, their views about using mobile phones to access the Internet and some strong opinions about the content and design of mobile Internet Web sites.

Using the Internet for Academic Research

Students regarded access to the Internet as an integral part of their academic life:

(I use the Internet) for absolutely everything. Why walk to the library if it's on the Internet. You just flick through it. Your university's signed up to all these journals and the journals are available to buy but you just look it up on the Internet. You don't even bother going to the library. (London Focus Group, female)

Most students had received some sort of training in using the Internet for academic research but the quality of this training varied greatly. For some it had been part of a Key Skills module at school, others were given the option of attending seminars run by their university library and some received more informal guidance from tutors. The training received was often of fairly limited scope and there was a perceived skills gap in many students who were not aware of the additional support and guidance available to them as their studies continued.

Views on the Mobile Internet

While ownership of mobile phones was virtually universal, the extent to which students accessed the Internet using their phones varied greatly. Only a small number ever used their mobiles for academic work. Cost and slow access to the Internet were identified as the main reasons for not using the mobile Internet. The availability of free, faster access via a PC at university or at home meant that there was little need to use mobiles for anything other than social purposes such as email or Facebook. Another factor was that very few students possessed new telephones with large screens, or had a contract with free Internet access and they also referred to the lack of compatibility of many Web sites with mobile phones.

Mine's quite bad actually ... quite poor so I don't really use it. I would if it was better, if it actually looked like the Internet pages then I'd probably use it more but at the minute I just do it for emails I really need … but the interface on mine isn't very good. (Manchester Group, female.)

This finding reinforced our intention to include a podcast as a project output, in addition to a mobile Web site, which can be downloaded easily and accessed at low cost on relatively low specification phones, or broadcast to users at no cost using Bluetooth.

However, mobile technology is changing fast and students were keen to trade up to the latest technology. Despite the current difficulties, many students stated that they would use the mobile Internet for their academic work if:

- their phones had larger screens

- it was quick and easy to load and navigate Web sites

- it was cheaper or free (included in their contract) to access the Internet

The pros would be that it's handy, it's like more convenient to be able to use it there and then but the cons would be I don't know, it's like too small to look at it on the phone and I don't know, it would be too fiddly I guess. (in-depth Interview, London, male)

A key theme which emerged was the need to summarise the content of the existing tutorial so that users would be able to load the mobile Web site quickly and navigate easily around the tutorial, with minimal time and cost. Students were very clear about what they expected from a mobile Web site:

I would consider using it if it's short and brief. If it's long I would just skip it straightaway …(in-depth interview, London, male)

It's way too big for mobile phones, too much information (London Focus Group, male)

To be honest as well this is not the kind of thing I'd use on my mobile. This is something that you do, you sit there and you learn it … Mobile Web sites are kind of like reference, a quick check … and you'd have to have a serious condensation of information there, you'd have to have one page – don't forget that, don't forget that. That would be the only way I'd probably look at it on the mobile. (Manchester Focus Group, female)

Overall it became clear that the content of the Internet Detective is very relevant and students were able to identify some elements of new knowledge in it. However, as we expected, the full tutorial was not the type of Web site they would use on a mobile phone. To make it appealing to mobile users would require a radical overhaul of the content.

Mobile Standards

One of the aims of the project was to deliver a mobile-optimised Web site that could reach the largest audience, regardless of their device. In embarking on such a project, consideration of standards to assist with mobile development would be a pre-requisite. The current standards in the mobile Web development world can be found at the W3C Mobile Web Initiative [11], whose stated goal is 'to make browsing the Web from mobile devices a reality'. The W3C has produced a working draft Mobile Web Application Best Practices [12] which builds on their earlier Mobile Web Best Practices 1.0 [13].

There are several options available to validate a mobile Web site. The W3C has produced an excellent tool called the mobileOK [14] checker, which will provide hints to fix your content. The Opera browser is good to check how your Web site will look to the majority of mobile users and then of course there are plenty of phone emulators available on the Internet like this one at dotMobi [15] (requires Java). However, there is no substitution for testing the Web site on actual phones with real users!

Mobile Content

An existing Web site, if produced with good structural mark-up, will probably render well on most mobile browsers, but sites designed for larger screens are often slow to load and hard to navigate even on zoom browsers. In addition, as reflected in our market research, the majority of mobile users still use lower specification devices, so they will not be catered for in a 'do nothing' approach.

To create mobile-specific content, one option would be to use a transcoder to convert existing Web site content to a more mobile-friendly format, but the downside to this is that content is surrendered to third-party interpretation and this does not take advantage of the mobile environment.

Another option is to use a mobile stylesheet, but problems exist with this approach due to the fact that 'media="handheld"' is not always recognised by devices.Equally, the problem of non-specific mobile Web site content and navigation would not be resolved.

The option chosen for the Mobile Internet Detective Project was to create a mobile Web site that was specific to the device, fast-loading, context-relevant and above all usable. Design and production considerations encountered during the project became apparent during testing and while conducting the market research.

Figure 1: View of the Web site using a mobile phone emulator

Some of the specific areas include:

- Automatic device detection – the project used Andy Moore's lightweight PHP script [16] which is free for non-profit Web sites. This gives the option of providing a full Web page for desktop browser users but redirects mobile users to the specific Web site. You may want to tailor your Web site for use on the iPhone for example, in this case the script can be tweaked to redirect per device. For full-featured mobile application development and detection you will need WURFL [17] or DeviceAtlas [18] and implemented with the programming language of choice.

- Domain name – think about how you want to market your Web site. At the time of the project JANET(UK) did not support .mobi type domains as far as the project team were aware. If you are part of the UK education sector you could buy a .mobi domain, use a sub-domain like m.yoursite.ac.uk or create a sub-directory within your current architecture like yoursite.ac.uk/mobile.

- Simple page structure and navigation – go right back to basics and simplify your information architecture, a one-column layout is probably all you need. Remove outbound links that do not point to mobile-friendly Web sites.

- Page styling – presentation effects must be defined separately from the content with CSS.

- Resize images – keep the use of images down to an absolute minimum and present them after important text. Do not try to reduce the image size on the fly, reduce them first, and store the new images on your server making sure you declare the new height and width within your mark-up.

- Anchor tags and access keys – in a content-heavy page that requires a lot of vertical scrolling; consider providing anchor tags or access keys to aid navigation within the page.

- Podcast – a podcast of your content is another good option for the mobile user, once downloaded to the device it will be available at no cost – if broadcast via Bluetooth, at a library induction say, there would be no download cost to the user at all.

- Short codes – these are the short numbers mobile users can text to say, receive a link to your Web site or provide feedback i.e. text the word 'like' to 12345. Short codes were too expensive to trial with the Mobile Internet Detective Project.

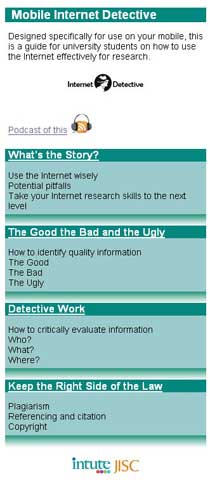

Figure 2: Close-up of the Web site home page

Lessons Learned

Based on the findings outlined above, the project team at Intute produced a final mobile prototype which is a heavily condensed and concise version of the original tutorial. The site is simple and easy to use with colour-coded links for easy navigation between sections. Links to external sites have been kept to a minimum and images have been removed to speed up loading time and keep connection costs down. Unfortunately cost limitations meant that we were unable to trial the use of SMS messages as a neat way to develop feedback mechanisms for users, but this would be something well worth pursuing in the future.

Obviously we have learned a great deal from our work on the project and would commend the light touch of the JISC programme management team which encouraged developers to connect with each other and share code and experiences rather than to get bogged down in documentation.

In some ways the simplicity and brevity demanded by mobile Internet users is difficult to reconcile with the traditional academic approach to providing learning materials. The new Mobile Internet Detective tutorial ended up losing much of its connection to the original, due to the huge amount of text and images which were cut from it. In retrospect it may have been easier to write a new tutorial from scratch rather than adapting existing content and attempting to reflect the character of the original, an approach which we increasingly abandoned with each re-write.

However, it is tempting to get too bogged down in the divide between mobile and non-mobile content and in fact we can translate many of the lessons learned from our experiences with mobile content to more traditional Web content. The desire for limited amounts of text and for separate chunks of information, rather than a linear text-based approach is a valid approach to the development of most online learning materials.

It is important to be guided by hardware developments as we look at future directions for mobilising learning materials. The recent launch of the iPad [19] indicates a demand from users for larger screens to access the Internet. However, we should also keep in mind the limitations experienced by users who do not have access to the latest technology. Future developments should include options for audio podcasts and video applications as well as text-based materials which are accessible to a wider range of users. Nevertheless, as mobile hardware improves over time and as new Web site content is created which adheres to current standards, the distinction between mobile and non-mobile content will become less important and accessibility should improve across the board.

The team working on the Mobile Internet Detective found it a really rewarding project. It provided us with some rich information about students' use of mobile technology in education and allowed us to apply that knowledge in practice. We will be making use of the experience gained with our colleagues in Mimas and are looking forward to doing more mobile learning work across other JISC-funded Mimas services in the future.

References

- From a presentation delivered by Boris Zetterlund, Manager Development Strategy, Axiell Library Group, at Online Information 2009 conference, 1-3 December 2009. Details at http://axiellarena.co.uk/

- Rapid innovation strand http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/inf11/jiscri.aspx

- Internet Detective http://www.vts.intute.ac.uk/detective/

- Mimas http://mimas.ac.uk/

- The Horizon Report 2010 Edition, The New Media Consortium/The EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative http://www.nmc.org/pdf/2010-Horizon-Report.pdf

- STROLL Final report, p.2 http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/elearningpedagogy/strollfinalreport.pdf

- Mobile Version of Hairdressing Training http://htmob.mobi/

- Intute Blog: Mobile Internet Detective http://www.intute.ac.uk/blog/category/mobile-internet-detective/

- UKOLN Events: Rapid Innovation in Development, September 2009 http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/events/jiscri-2009/

- Developer Community Supporting Innovation (DevCSI) http://devcsi.ukoln.ac.uk/

- W3C Mobile Web Initiative http://www.w3.org/Mobile/

- Mobile Web Application Best Practices, W3C Working Draft 6 October 2009 http://www.w3.org/TR/2009/WD-mwabp-20091006/

- Mobile Web Best Practices 1.0: Basic Guidelines, W3C Recommendation 29 July 2008 http://www.w3.org/TR/mobile-bp/

- W3C mobileOK Checker http://validator.w3.org/mobile/

- dotMobi http://emulator.mtld.mobi/emulator.php

- Detect Mobile Browsers - Mobile User Agent Detection http://detectmobilebrowsers.mobi/

- WURFL (Wireless Universal Resource File) http://wurfl.sourceforge.net/

- DeviceAtlas http://deviceatlas.com/

- Apple (United Kingdom) - iPad http://www.apple.com/uk/ipad/