Usability Inspection of Digital Libraries

Demands for improved usability and developments in user experience (UX) have become pertinent due to the increasing complexities of digital libraries (DLs) and user expectations associated with the advances in Web technologies. In particular, usability research and testing are becoming necessary means to assess the current and future breeds of information environments such that they can be better understood, well-formed and validated.

Usability studies and digital library development are not often intertwined due to the existing cultural model in system development. Usability issues are likely to be addressed post-hoc or as a priori assumptions [1]. Recent initiatives [2] have advanced usability studies in terms of information environment development. However, significant work is still required to address the usability of new services arising from the trends in social networking and Web 2.0.

The JISC-funded project, Usability and Contemporary User Experience in Digital Libraries (UX2.0) [3], contributes to this general body of work by enhancing a digital library through a development and evaluation framework centred on usability and contemporary user experience. Part of the project involves usability inspection and research on contemporary user experience techniques. This article highlights the findings of the usability inspection work recently conducted and reported by UX2.0 [4]. The report provided a general impression of digital library usability; notwithstanding, it revealed a range of issues, each of which merits a systematic and vigorous study. The discussion points outlined here provide a resource generally useful for the JISC Community and beyond.

Objective and Aims

The objective of the usability inspection of UX2.0 was to elicit thinking and applications of usability studies for digital library development. The aims are:

- To gauge the overall usability standard of established DLs

- To identify positive examples of good usability

- To recognise the unique aspects of each DL and evaluate to what extent they enhance the user experience

Test Subjects

It is important to note that the findings discussed are limited to the selected test subjects and the method used to evaluate each DL. The test subjects chosen were lent from the WorldCat usability testing report [5]. From tests conducted on WorldCat, researchers identified that academic users favour searching local, national and worldwide collections together as opposed to public library patrons who are interested in resources which are geographically close. Using this finding as a basis for choosing test subjects, a range of digital libraries was chosen that fitted the following criteria:

- Public digital libraries (DLs) instead of commercial publisher sites such as ACM and Web of Science;

- Resources that fitted into one of 5 geographic categories; worldwide, European, nationwide (UK), regional (Scotland) and local (Edinburgh);

- DLs that presented the contents of a traditional library as well as those that presented a group of items which existed across many different traditional libraries.

Using these criteria the digital libraries that were selected are identified in Table 1.

Attribute | Digital Library | Web address |

Worldwide | World Digital Library (WDL) | |

European wide | Europeana | |

Nationwide (UK) | British Library (BL) | |

Regional (Scotland) | Scran | |

Local (Edinburgh) | University of Edinburgh (UoE) Aquabrowser |

Table 1: Digital library test subjects

What is an Heuristic Evaluation?

An heuristic evaluation is a discount method [6] used to help identify usability problems with a user interface design. Typically it is carried out by a number of evaluators who examine the interface and judge its compliance with recognised usability heuristics. Heuristic evaluation was chosen as a robust method of uncovering usability issues. It provided a checklist of sorts which could aid the evaluator in systematically deconstructing the usability of each DL in the absence of testing with real users. However, there are several limitations to this method which should be noted. Ideally heuristic evaluations should be carried out by more than one professional. Doing so ensures cross-validations and that the maximum number of usability issues is uncovered. As a more detailed evaluation will be carried out on the digital library currently being developed in UX2.0, the inspection report is mainly exploratory and seeks to highlight existing usability issues instead of providing an exhaustive usability study involving all test subjects.

The digital libraries were inspected using two separate sets of established usability heuristics:

Usability Heuristics by Jakob Nielsen

The first is a list of 10 heuristic principles created by Jakob Nielsen in 1994 [7]. Nielsen’s heuristics have been extensively used for the purpose of usability inspections and are well respected amongst usability professionals:

- Visibility of system status

- Match between system and real world

- User control and freedom

- Consistency and standards

- Error prevention

- Recognition rather than recall

- Flexibility and efficiency of use

- Aesthetic and minimalist design

- Help users recognise, diagnose and recover from errors

- Help and documentation

ISO Heuristics 9241

The second set is a list of heuristic standards laid out by the International Organisation for Standardization. The heuristics are outlined in BS EN-ISO 9241-110: Ergonomics of human system interaction - Part 110: Dialogue Principles. This part of ISO 9241 presents a set of usability heuristics that applies to the interaction of people and information systems (the heuristics are based on an earlier German standard). The standard refers to this interaction as a “dialogue” and describes seven “dialogue principles” [8]. The ISO Dialogue Principles provide an alternative to Nielsen’s heuristics and are based on widespread research:

- Is the dialogue suitable for the user’s tasks and skill level? (Suitability for the task)

- Does the dialogue make it clear what the user should do next? (Self-descriptiveness)

- Is the dialogue consistent? (Conformity with user expectations)

- Does the dialogue support learning? (Suitability for learning)

- Can the user control the pace and sequence of the interaction? (Controllability)

- Is the dialogue forgiving? (Error tolerance)

- Can the dialogue be customised to suit the user? (Suitability for individualisation)

Together these sets provide an exhaustive list of contrasting and complementary principles with which to carry out the evaluation. The aim of using these heuristics is to uncover usability issues effectively as well as identify positive design features.

The Advanced Search Debate

The usefulness of advanced search is often a contentious issue. Given the advent of simple and alternative search tools, users often eschew advanced search. Therefore advanced search is often an underused feature, which should be ‘gotten rid of’ [9]. For example, WDL and UoE’s Aquabrowser do not provide advanced search forms, preferring to provide alternative ways for users to search. The lack of advanced search may be challenged by the usability heuristics that state accelerators should be provided to speed up interaction for the expert user (Nielsen’s Heuristic 7). Providing choice for users ensures that every type of user is catered for. Certainly, omitting an advanced search has the potential to do more harm than not including it.

However, there is another argument that places less value on the inclusion of the advanced search than on how easy it is to use. For example allowing inexperienced users to undertake advance search without imposing a steep learning curve could encourage usage and improve search experience. All advanced search forms examined in the inspection had multiple blank fields, each associated with a drop-down menu, uncommon labels and very little instruction on how to complete the form. Other usability issues encountered during the inspection are more generic. For example, the use of small and indistinguishable links as action buttons in the middle of the search form, cf. Fitts Law (User Interface selection dependency based on size and distance) [10].

One approach to address usability of advanced search has been more fundamental. Instead of search fields in self-contained forms, the approach is based on the design of alternative tools that embed advanced search to provide more intuitive user experience. Most of the digital libraries inspected, for example, provide Faceted Searching which essentially facilitates reconstituted and iterative Boolean search operations.

One social media (Twitter) search engine, Tweetzi, provides a good example of how alternative tools can act as a substitute advanced search form (Figure 1). Tweetzi has designed icons which reveal a description of their purpose when a user hovers over it. Providing these tools simplifies the search process and encourages user learning as recommended in ISO Heuristic 4. For example, searching for an exact phrase is automatically generated by wrapping inverted commas around the string at the push of a button (short-cut of multiple user interactions). Users can also search for links, hash tags (Twitter search vernacular for user-generated keywords), questions and positive or negative statements using similar buttons. These advanced features are basic but still powerful because they are not promoted as advanced features, making them more accessible. As a result, more users are likely to utilise them and learn about constructing complex searches in the process. This approach may not replace the traditional advanced search form but has potential to bridge the gap for less experienced users.

Figure 1: Tweetzi search tools

Emerging Interaction Design Patterns

During the course of the inspection, new interaction design patterns and ways of facilitating resource discovery have been identified. Some of these techniques are not necessary new per se. Many have been prevalent among existing Web sites especially under the guise of Web 2.0. However, their application in digital libraries is both novel and increasingly widespread. An objective of UX2.0 is to delineate interaction design patterns of common usability challenges and evaluation aspects.

In addition to Faceted Searching as described above, the DLs inspected in our study are piloting systems based on emerging interaction design patterns such as Dynamic Queries, Carousels, Tag Clouds, Spatial Navigation and Intriguing Branches [4]. For example, WDL provides a timeline and interactive (map) browsing User Interface (UI) which is based on a composite use of design patterns aforementioned. Users can manipulate the timeline (slider) to change the scope (query) dynamically of all items available on display via expandable image carousels in the interactive map.

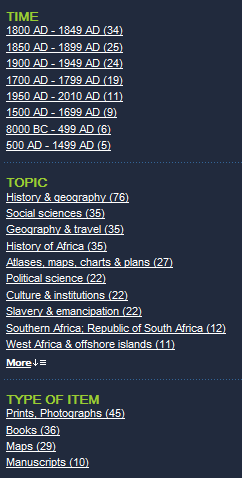

Most of these interaction patterns rely on advanced (AJAX) UI techniques and a high degree of user manipulation. This inevitably gives rise to usability and accessibility problems, some of which have been identified in UX2.0’s inspection, e.g. inconsistent behaviour of WDL interactive map (links) and carousels controls (usability). Despite the usability problems, these design patterns and their composite usages are useful especially for those who do not know exactly what they are looking for. For example, faceted searching/navigation services (Figure 2) of WDL, Europeana and UoE Aquabrowser integrate searching and browsing to let users begin with a simple keyword search, but then help users frame their choices by allowing them to reduce the number of possible matches to their search [11].

Figure 2: Section of World Digital Library’s Faceted Navigation

Indeed a general finding from the inspection indicates a trend in which searching and browsing experiences are becoming increasingly integrated. In particular, faceted searching provides a ‘navigational metaphor’ for Boolean search operations, which are typical of advanced search. Early user studies have suggested a propensity of faceted searching to result in greater user satisfaction and serendipitous discovery [12]. These systems have the potential to facilitate better ways of searching: fast drill-down of results; enhanced search context; and to speed up searching and create a feeling of effortless control by concentrating the user’s task [13]. It seems that the primary target users of such systems are inexperienced users as well as those who do not know exactly what they are searching for. However, emerging evidence [12] already indicates potential benefits for expert users also. The usefulness of the systems is less clear and something which requires rigorous user studies to validate.

Navigation

Faceted navigation (search) was found to be one of the most commonly used methods implemented for resource discovery in DLs. This is supported by a report on the assessment of the NCSU Endeca catalogue [14] which states that progressive refinement through facets account for 45% of keyword searches. The inspection also showed that faceted navigation can also enhance the user experience by providing greater control over a search and speed up browsing of results as recommended in Nielsen’s Heuristic 3. This is supported by usability testing comparing the Endeca catalogue to the traditional catalogue which showed significant improvements in task completion times, task success rates and perceived ease of use [14]. Additionally, the research by Olson [12] shows that faceted search can facilitate the discovery of new items previously undiscovered through traditional search methods.

However, the inspection showed that considerations need to be made when implementing faceted navigation. Allowing users to select multiple categories is an emerging and advanced feature of faceted navigation. It should also be clear to users what results are being provided. Selecting two facets could create different impressions for different users. Does the action mean all items (OR Boolean operation) or common results (AND Boolean operation) from multiple categories? The inspection showed that Europeana had difficulty clarifying these issues. Visual feedback should be provided to clarify the scope of search to the users. Doing so will allow them to feel in control of their search and to manipulate it effectively to meet their needs (Nielsen’s Heuristic 3).

Faceted navigation should also present categories in a manner that makes sense to users and meets their expectations. The report found that in some cases the default order of presenting categories is questionable. Currently, the most popular and default presentation is facets in a descending order based on the total number of matches. This default setting assumes a preference for large result sets. Such bias is arguably caused by the system limitation (screen estate) of faceted navigation (in presenting all facets). This assumption ought to be challenged through usability testing, and other forms of facet ordering should be experimented with. For example, date or period type facets can be presented chronologically (with the option to change the order by number of results) and subject headings, alphabetically. Such presentations at least enable users to scan and select facets in ways which reflect their mental models, as demonstrated by the efficacy of the publication date facet of AquaBrowser. Nevertheless, this attempt is not prevalent as witnessed during the inspection, e.g. the confusing time facets of WDL (see Figure 2).

Social Networking Development

There was evidence from the inspection report to suggest that DLs are incorporating social media tools to enhance the user experience. The inspection revealed two different strategies in providing a social outlet for their users: rudimentary integration with established communities or creating a custom community local to the library. BL adopted the first approach with sharing services which redirect users to a variety of external social networks. Scran and Europeana have adopted the latter solution. However, Europeana’s social network is still under construction.

The rise in popular social networks such as Facebook can often act as a suitable and acceptable outlet for users. As an established network, it has the benefit of being familiar to users, of reducing reliance on the latter to learn to use a new interface (ISO 1). Additionally, existing software such as the built-in social networking module provided by Aquabrowser (My Discoveries) removes the need to build a social network from scratch and cultivate a community of regular users. Aquabrowser can connect to users from other Aquabrowser libraries (although UoE currently does not have this service), allowing DLs to grow a successful community much faster.

However users have finite ‘social currency’; most have a legacy of existing communities with which they are already interacting. It is a real challenge for DLs to devise ingenious ways that integrate seamlessly with users’ workflow and existing communities. The social networking features of the test DLs are either shallow integrations or preliminary and untested prototypes (probably an indication of the challenging and resource-intensive aspects of building a social network). Currently, both are unlikely to realise the full potential of social networking. It remains to be seen if these and other DLs will find the means to devise a ‘third way’ - a local community which is also fully interoperable with existing social networks.

Conclusion

The findings from the inspection report revealed several trends in DLs that suggest more choice is being provided to users when searching for information. The traditional approach to searching is being complemented by other systems which not only provide variety for users but also help to increase the sophistication of search making it quicker and easier for users to find what they are looking for. In addition, new interaction patterns are being introduced and coincide with the increasing use of dynamic user interface of the Web 2.0 trend. However, the inspection uncovered usability issues and showed that improvements are required to ensure the systems are easy to use.

Web 2.0 sites are directly influencing DLs by encouraging more personalisation and social interaction. Many of the DLs inspected provide a personal section where users can save items and share them with others within a gated online community or through established external social networks. The rise in popularity of social networking has generated a new online culture where users expect social services to be provided. The increasing prevalence of such services in DLs is a positive trend which will, we hope, continue to develop.

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the JISC Information Environment Programme 2009-11 15.

References

- Blandford, A., Connell, I., & Edwards, H., Analytical Usability Evaluation for Digital Libraries: A Case Study, I, 2004

- Glosiene, A., & Manzuch, Z., Usability of ICT-Based Systems, State-of-the-Art Review, Calimera Project Deliverable 9, 2004

- JISC Usability and Contemporary User Experience in Digital Libraries project http://bit.ly/jiscux2

- Paterson, L. & Low, B., Usability Inspection of Digital Libraries – Full Report http://bit.ly/ux2inspectionreport

- WorldCat, Some Findings from WorldCat Local Usability Tests, Prepared for ALA Annual, July 2009

- Nielsen, J., Heuristic Evaluation http://www.useit.com/papers/heuristic/

- Nielsen, J., Heuristic Evaluation, Nielsen, J., & Mack, R.L (Eds.), Usability Inspection Methods, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, 2004

- BS EN-ISO 9241-110: Ergonomics of human system interaction - Part 110: Dialogue principles

http://www.userfocus.co.uk/resources/iso9241/part110.html - Nodder, C., Application Usability workshop, Usability Week, 2009, Berlin

- Scott Mackenzie, I., Fitts’ law as a research and design tool in human-computer interaction.

Human-Computer Interaction, volume 7, 1992, pp. 91–139., 1992 - Morville, P. & Callender, J., Search Patterns, O-Reilly Media, California, 2010

- Olson, T.A., Utility of a faceted catalogue for scholarly research, Library Hi Tech, 2007, 25(4), p. 550-561

- Scott, B. & Neil, T., Designing Web Interfaces, O’Reilly, California, 2009

- Antelman, K., Lynema, E., & Pace, A.K, Toward a twenty-first century library catalogue, Information technology and libraries,

American Library Association, 2006, 25 (3), p. 128-138 - JISC Information Environment Programme 2009-11 http://www.jisc.ac.uk/whatwedo/programmes/inf11.aspx