Europeana Open Culture 2010

The Europeana Conference is a free annual event which highlights current challenges for libraries, museums, archives and audio-visual archives and which looks for practical solutions for the future. It connects the main actors in cultural and scientific heritage in order to build networks and establish future collaborations. The Europeana Open Culture 2010 Conference [1] was the third annual conference and the biggest so far. It focused on how the cultural institutions can create public value by making digital, cultural and scientific information openly available.

The conference attracted more than 360 people from every country in Europe to explore the risks and rewards of openness - of code, data and content - and showcase sites and activities that are the best European examples of Open Culture. Amongst the speakers were representatives of Google Books, Wikipedia, Creative Commons and the European Commission. As usual, many pre-conference and post-conference meetings clustered around the event involving, for example, the Europeana Foundation Board, the newly formed Council of Content Providers and Aggregators, and Europeana v1.0 workgroup members.

A Word about Europeana Itself

Europeana.eu is about opening access to Europe's cultural and scientific heritage and making Europe's rich and diverse content easily available to users whenever they want and wherever they are. It's also about giving material from trusted sources, and how these sources can keep up with evolving needs of their users, especially the Web 2.0 generation. For the institutions involved, which number more than 1500 content providers already, Europeana provides a unique opportunity to open up their collections to millions of users from all across Europe as well as other parts of the world. It is a means to drive more traffic to their sites, since Europeana always refers to the original source of the material. Europeana also brings institutions from the cultural and scientific sectors together and facilitates knowledge exchange among them, providing a way to learn about new projects, best practices and technological developments in the heritage sector. It also helps institutions build and expand professional networks, meet potential project partners, and be part of a key initiative that continues to attract strong endorsement from the European Commission.

Elisabeth Niggemann, Chair of the Europeana Foundation, welcomes the delegates.

"Europeana is the EU's most visible expression of our digital heritage," the European Commissioner Neelie Kroes said in her opening speech at the Audiovisual Archives in the 21st Century (AVA21) Conference [2] in Ghent, Belgium, on 13 October 2010. Indeed, currently Europeana gives multilingual access to over 13 million items. It shares diverse content from world famous works to hidden treasures, from books to film, inspiring innovation, creativity and collaboration.

Conference Overview

Jill Cousins, Director of Europeana Foundation

Jill gave the first presentation at the conference and explained that Open Culture 2010 was about openness: open content, open data, open source code; and how museums, libraries, archives and audio-visual collections can create public value by making digital, cultural and scientific information openly available. Jill began with the question 'What are we now?' She noted Europeana's progress from prototype to public service over the last two years and highlighted key developments Europeana has to take into consideration to remain pertinent to its stakeholders, namely, users, content providers and policy makers.

Open Culture 2010: More than 360 people from all across Europe participated in the conference.

There is increased political and economic understanding that access to culture is the foundation for a creative economy. Culture is perceived to lead to creativity, which in turn leads to social innovation and to cultural and economic growth. With geo-political fragmentation and growing nationalism in Europe, politicians believe it is increasingly important to create more understanding on a European level through culture. At the same time, potential end-users of Europeana are evolving from passive consumers into active participants. They expect content to be free and easily accessible through the channels with which they are used to working. Cultural institutions, on the other hand, have to deal with major intellectual property rights (IPR) issues at a time when a lack of funding and of good business models limit their ability to make content accessible, while digitisation requires them to make significant shifts in their organisational cultures. Europeana, for its part, has to relate positively and effectively to users, content providers and policy makers, and constantly adapt to the present realities of the market.

Having set the scene, Jill moved on to answer the questions "What should we be?" and "What shall we do?" Europeana sees its future as following four main paths. Firstly, it will aggregate content and build the open trusted source for European digital cultural material. Secondly, it will distribute this material and make it accessible to users wherever they are, whenever they want it. Thirdly, it will facilitate innovation in the cultural heritage sector. Fourthly, to achieve these aims, it will continue to engage all the relevant players to create dialogue, participation and increasing consensus.

Conference Themes and Structure

Besides plenaries and keynotes, the conference offered three parallel thematic tracks on the key topics in the heritage sector:

- linked data;

- user-generated content; and

- the risks and rewards of opening up data and content.

Thematic Tracks

Three lead experts briefly introduced the three main themes of the conference, after which delegates went into break-out sessions on each of the themes. In these interactive sessions, conference participants formed discussion groups, where they shared their experience, exchanged ideas, addressed main challenges, and looked for practical solutions. The panel of specialists helped moderate these discussions, offering their indispensable expertise and capturing main outcomes of the discourse.

Applications of Conference Themes

Several Web initiatives were presented the next day, demonstrating outstanding applications of the conference themes:

- 1001 Stories about Denmark – User-generated Content

- Solar Stormwatch - Crowdsourcing

- BBC Wildlife Finder - Linked Data

- Institut National de l'Audiovisuel – Remixing content (unfortunately, the speaker was unable to present but the presentation is available)

These Web initiatives demonstrated the rewards that opening up brings, since their popularity and success emanates from their commitment to openness and making information widely available.

Linked Data

Interest is growing in the potential of the semantic web to link online data and, by so doing, create a powerful resource for knowledge sharing and creation. Europeana's vast authority-controlled metadata index provides a critical mass of raw material for innovative experiments. Together with its related projects, Europeana offers a unique locus from which to link cultural heritage data sources.

Applications can be developed that follow their noses through overlapping or complementary sets of data, making connections as they go. Culture's institutional linked data can make use of these applications and benefit from enrichment and connection to other domains' data, or to user-generated data. Delegates were invited to consider case studies and think about questions such as possible usage scenarios envisaged for cultural linked data, how the cultural heritage domain should position itself to take advantage of these opportunities and Europeana's role in facilitating this process.

User-generated Content

Folksonomies, Flickr commons and Wikipedia highlight the value of the user's contribution – a value starting to be taken seriously by the professional heritage expert. Users' specialist information, their unique artefact, their photo of a monument, of planets, of people, etc, can make an important contribution to the historic record or lead to scientific discoveries.

Whilst there is recognition of the value of user-generated content, there are practical issues around implementation. Delegates therefore focused on one main issue: how can heritage organisations – and Europeana - best harness users' enthusiasm, authenticate their offerings and mediate their engagement?

Risks and Rewards

Opening up data or content for reuse, potentially in a commercial context, can seem a high-risk strategy for heritage institutions. On the other hand, the rewards in terms of new applications, innovation and creative enterprise have wide social benefits. Equally, institutions need to remain relevant in the 21st century; to wall off their content is to risk marginalisation. This is why they find themselves continually engaged in a struggle to solve an equation with two unknown variables: the risks of opening their content; and the returns, both financial and promotional, that such openness can generate.

The issues considered by delegates in this stream included:

- Does openness threaten current revenue streams, control over data standards and content, or scholarly standards of provenance and authentication?

- What are the legal risks of digitising and displaying orphan works online?

- How do we manage the dichotomy of making money while honouring the public domain?

- What are the potential rewards; and how can Europeana help to secure them?

Keynote Speech 1: Peace, Love and Metadata: A Cultural Collaboration with Wikipedia

Liam Wyatt, the British Museum's first Wikipedian in Residence

Liam Wyatt (a.k.a. 'Witty lama'), the first Wikipedian in Residence, rightly pointed out in his keynote speech that people always overestimate risk and underestimate reward in the digital world. If given a chance, rewards can be huge, in terms of engagement with users, hits on institutions' sites, and revenue streams. Liam sees it as his role to build bridges between the free and open Internet as represented by Wikipedia and the 'GLAM sector' [3] as representatives of the knowledge industries. The aim of Wikipedia is to make all human knowledge available to all in their own language, an aim with which cultural institutions can surely sympathise. The issues are how can we create and share culture in a way that is relevant to the 21st century? Wikipedia and libraries have not related to each other much in the past, but now they are beginning to do so. Wikipedia needs the expertise of librarians and curators to continue improving its product, whereas the GLAM sector can greatly benefit from the Wikipedia's massive user base. So the question is what they can do to ensure both sides benefit. The British Museum residency was a pilot project to investigate this matter without either side needing to change its major policies.

As Wikipedian in Residence, Liam aimed to build a relationship between the Museum and the Wikipedian community through a range of activities both internally and public-facing. These activities included: creating new or expanding existing articles about notable items or subjects of specific relevance to the collection and the Museum's expertise; supporting Wikipedians already editing articles related to the British Museum both locally and internationally; and working with Museum staff to explain Wikipedia's practices and how they might be able to contribute directly.

Among the various results of the pilot was better (and wider) Wikipedia coverage of many aspects of the Museum's collections, and greatly increased online exposure for the Museum, both through Wikipedia and by click-throughs to its own site. Liam pointed out that many GLAM institutions have volunteer organisations, but as yet they lack digital volunteer programmes or e-volunteers, something which represents an area of significant opportunity.

Keynote Speech 2: The Present and Future of Google Books

James Crawford, Engineering Director of Google Books

James explained that his job is to organise the world's books and make them universally accessible and useful. So far about 15 million books have been scanned. Google estimates that there are about 130 million books. Of those, some 2.5 million are public domain, 2.5 million in print, and the rest (more than 100 million) are only available through libraries. He stated that Google was looking at how to rank books in terms of their popularity or relevance to a searcher. This was an area where librarians had relevant expertise.

Access to public domain books is greatly increased by scanning and access to all books is increased by indexing them. Sales of in-print books should also increase through increased awareness.

The European Commission's Perspective

Luca Martinelli of Directorate General Information Society and Media of the European Commission

Luca recalled that Europeana and its related projects had been funded through the eContent plus Programme and that the Competitiveness and Innovation (CIP) Framework Programme continued to make financing available for projects on content aggregation and digitisation, including co-funding Europeana under CIP until the end of 2013 [4]. Furthermore, the Commission's Digital Agenda for Europe [5] has this as its Key Action 15:

'By 2012 the Commission will propose a sustainable model for financing the EU public digital library Europeana and digitisation of content.'

The Commission has other policy initiatives underway that support Europeana's work. It plans to create a legal framework to facilitate the digitisation and dissemination of cultural works in Europe by proposing a Directive on orphan works in 2010. This will invite the stakeholders to explore further measures on out-of print works, complemented by rights information databases.

Other elements of the Digital Agenda state that:

'Fragmentation and complexity in the current licensing system also hinders the digitisation of a large part of Europe's recent cultural heritage. Rights clearance must be improved, and Europeana - the EU public digital library - should be strengthened,' and

'The Commission by 2012 will review the Directive on Re-Use of Public Sector Information, notably its scope and principles on charging for access and use.'

From now to 2020 through the European Digital Agenda, the Commission will continue its efforts to bring European cultural heritage online and bring about convergence towards openness by addressing issues such as open source, open standards, open access, open data, open content and open culture.

Launch of Public Domain Mark

The finale of the Open Culture 2010 Conference was the launch of the Public Domain Mark in association with Creative Commons [6]. This mark will enable works free of known copyright restrictions to be labelled in a way that clearly communicates that status. With the use of the mark, public domain works will be easily discovered over the Internet, making them more readily accessible to the public. The mark also makes it clear to teachers and students, artists and scientists, that they are free to reuse material. Its release benefits everyone who wishes to build upon the rich and vast resources that are part of the shared public domain. On the Europeana portal, the Public Domain Mark will become the standard symbol for works free of known copyright. It will play an important infrastructural role in the EU's efforts to ensure that all works shared online are marked with rights information.

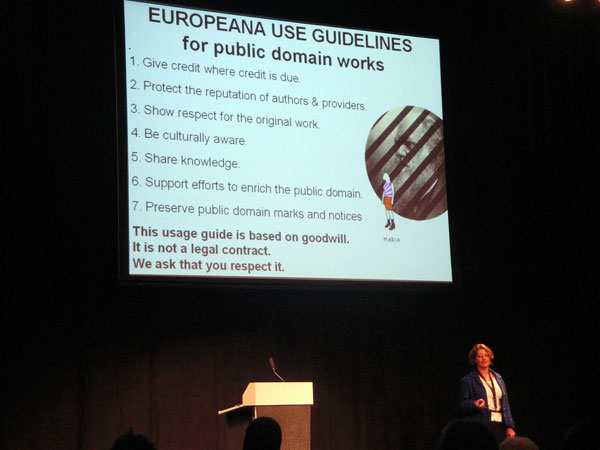

In addition, Europeana also published the Usage Guide for public domain works. This is not a legally binding contract, but a token of goodwill. It calls for endorsing efforts to enrich the public domain, giving credit where credit is due and showing respect to original work. The public domain mark further supports the Europeana Public Domain Charter [7] which was launched in May 2010 and which articulates the view that the Public Domain must be preserved, and that works in the public domain should not be removed from the public domain when they are digitised.

Jill Cousins presenting the Public Domain Mark

Conclusion

The Europeana Open Culture 2010 Conference was simply great! This is what you could hear participants saying, tweeting, and blogging. Moreover, a remarkable venue (a disused gas works!), an interesting programme, inspirational speakers and terrific audience.

The event marks another step in Europeana's progress from being a concept (the European Digital Library) to becoming a real service, a force in policy development and advocacy for the cultural heritage sector in Europe and a player on the world stage of open digital culture in the age of Web 2.0. Europeana is not afraid to address the big issues and is moving forward at impressive speed. In Amsterdam the GLAMs were listening and taking heed.

For readers who want more details of the event, the presentations are available [8] on the conference site and the video blog This Week In Libraries features interviews with some of the Europeana conference speakers [9].

References

- Europeana Open Culture 2010 home page http://version1.europeana.eu/web/europeana-plenary-2010/

- Audiovisual Archives in the 21st Century (AVA21) Conference, October 2010 http://www.ava21.be/en/index.php

- GLAM: A 'wikimedian' term for 'galleries, libraries, archives and museums'!

- See: The Europeana group for the current list http://version1.europeana.eu/web/guest/home

- Europa - Information Society: Digital Agenda for Europe http://ec.europa.eu/information_society/digital-agenda/index_en.htm

- Creative Commons: Public Domain Mark 1.0 http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

- Europeana: Publications: project http://version1.europeana.eu/web/europeana-project/publications/

- Europeana: Presentations: 14 October 2010 http://www.group.europeana.eu/web/europeana-plenary-2010/presentations/

- Video blog This Week In Libraries: interviews: TWIL #24: Europeana Open Culture Conference http://vimeo.com/15904526