Walk-in Access to e-Resources at the University of Bath

Kate Robinson, Lizz Jennings and Laurence Lockton outline a low-cost solution to walk-in (visitor) access to licensed e-journals, drawing on their practice at the University of Bath with a wiki ERM and OPAC terminals.

Although the move from print to electronic journals over the last two decades has been enormously beneficial to academic libraries and their users, the shift from owning material outright to renting access has restricted the autonomy of librarians to grant access to these journals.

The Problem

Licence restrictions imposed by publishers define and limit access rights and librarians have increasingly taken on the role of restricting access on behalf of the publisher, rather than granting access on behalf of their institution. In other words, librarians and their institutions are no longer free to decide who may read this material as they no longer own it.

This situation has been the subject of negotiation for some time, and it is fair to say that an accommodation has been reached in many cases through less restrictive licensing terms. Some clearer definition of groups who can use e-journals has eased the situation for 'authorised users', such as those teaching students of an institution who are not directly employed by the institution itself, for example, through franchised courses. However, there is still a group of potential users who do not have a relationship with an institution other than a wish to access the Library's holdings to further their research or their curiosity. In the past, such access was at the discretion of the Librarian but with regard to e-journals it is now set out in publishers’ licences, usually under the terms of 'walk-in access' to these resources. This in itself is a positive move and seemingly restores some access control to the Librarian. In practice, however, it has not proved to be straightforward to implement.

In general terms e-journal access, although via the Web, piggybacks on established University IT systems and safeguards which have not always been specifically designed to support the licence restrictions of publishers. The definition of an authorised user for walk-in access is usually one who has been granted access to the Library building. This requirement for e-journal material to be restricted to the actual library building, not just University premises, presents a technical challenge. It is not reasonable to expect a University's IT infrastructure to be redesigned to accommodate the needs of those who are not part of the institution. However, there is a balance to be struck as a tipping point has been reached, with journal holdings become increasingly e-only and widening participation becoming increasingly important to institutions.

There are a growing number of groups who would like would and benefit from walk-in access. In recent years requests for access to e-journals have become more frequent from library users, such as researchers who already use and borrow hard-copy materials through the SCONUL Access scheme, and school/college students undertaking Extended Project or International Baccalaureate qualifications. Clearly it is desirable to support the research community of which we are part, and to encourage EP/IB students whose next steps may well be into Higher Education. Visits for school/college groups are increasingly encouraged at institutional level and often include teaching and other intensive support from library staff; support which increases as the range of material they are authorised to access decreases. Research areas and subjects for these pieces of work are diverse and cannot be easily satisfied through textbook material or residual hard-copy journal holdings. In this climate, we need to look again at how to implement walk-in access to open up resources wherever possible. To do this we first need to take two steps: to identify which online material we can allow access to and to facilitate access through a route which meets licence terms, that is, to this material only within the library building.

The Solution: Identifying Licence Terms

Background

The University of Bath Library has been managing an electronic resource collection for several years, but as with many HE institutions, this activity has expanded and gathered a vast quantity of information in its wake. As deals and licences change, it is important to manage this information effectively, and many institutions have purchased or developed Electronic Resource Management (ERM) systems.

With budgets stretched tightly, it was important that we were able to manage our resources, while retaining as much budget as possible for the purchase of the actual resources themselves. We had little information about our licences outside the documents themselves, which had usually been studied before signing, but no further analysis had been undertaken once the resource was established. Additionally, there was often a large amount of information from publishers and from subject librarians about decisions and clarifications which resided in people’s personal email inboxes. This information was usually remembered by those who had received it, but when making decisions or solving problems in the absence of these people, key facts were often obscured.

It became clear that a central resource which gathered together these strands of information in a structured and accessible way would be very useful. The e-resources team at Bath had seen a number of demonstrations of commercial ERM systems, and decided to assess our options. Three possibilities were considered: using a commercial ERM, using an open-source ERM, or using our existing Confluence wiki-based intranet. It soon became apparent that whichever system we chose, we would need to spend a considerable amount of time and effort in gathering the relevant information to populate it. Although some commercial ERM systems had a level of automation, we were concerned that their default options would not represent our own agreements, and that detailed checking would be required. Open Source ERMs were an attractive alternative, but would require additional systems expertise to customise. The wiki had the advantages of being already installed, familiar to and accessible only to all library staff, as well as being editable by any of them, but did not offer the same flexibility to link resources or extract reports.

Approach

We decided to use the existing wiki and build our own databank. This offered us complete flexibility in choosing which items of information to record, and could either be a starting point for future migration to a more powerful system, or a final system in its own right, depending on how successful it was. We agreed that gathering the information together in some format was a necessary first step in understanding our licences and resources.

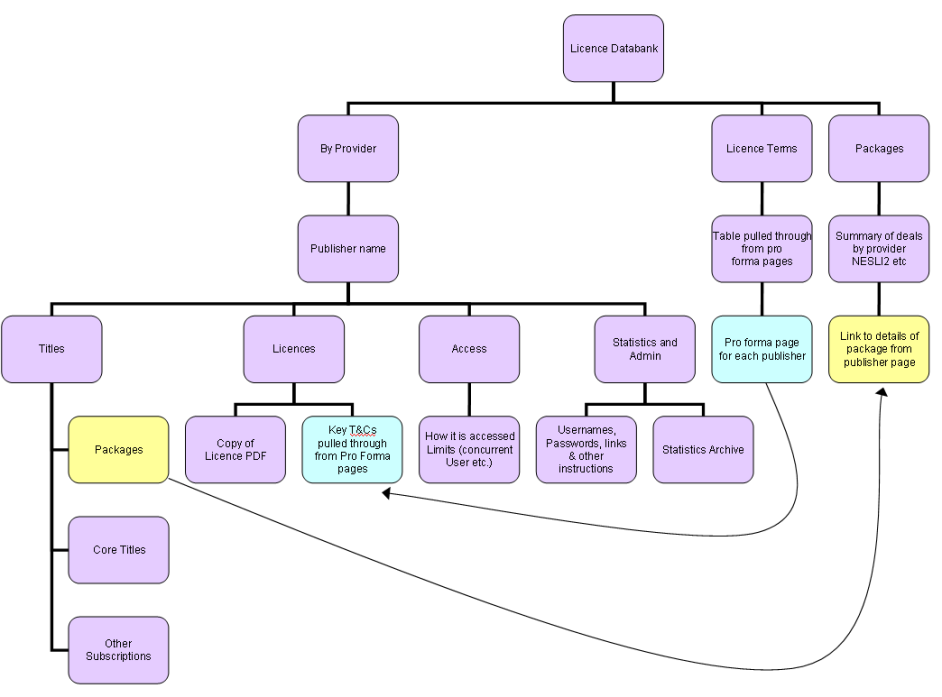

The databank was originally designed using a basic hierarchy of sections:

Figure 1: Hierarchy of wiki pages for the e-resources databank

This design pulled together existing sections of the wiki, such as the statistics collection, with information about licence terms and conditions, access information, title lists and information about decisions.

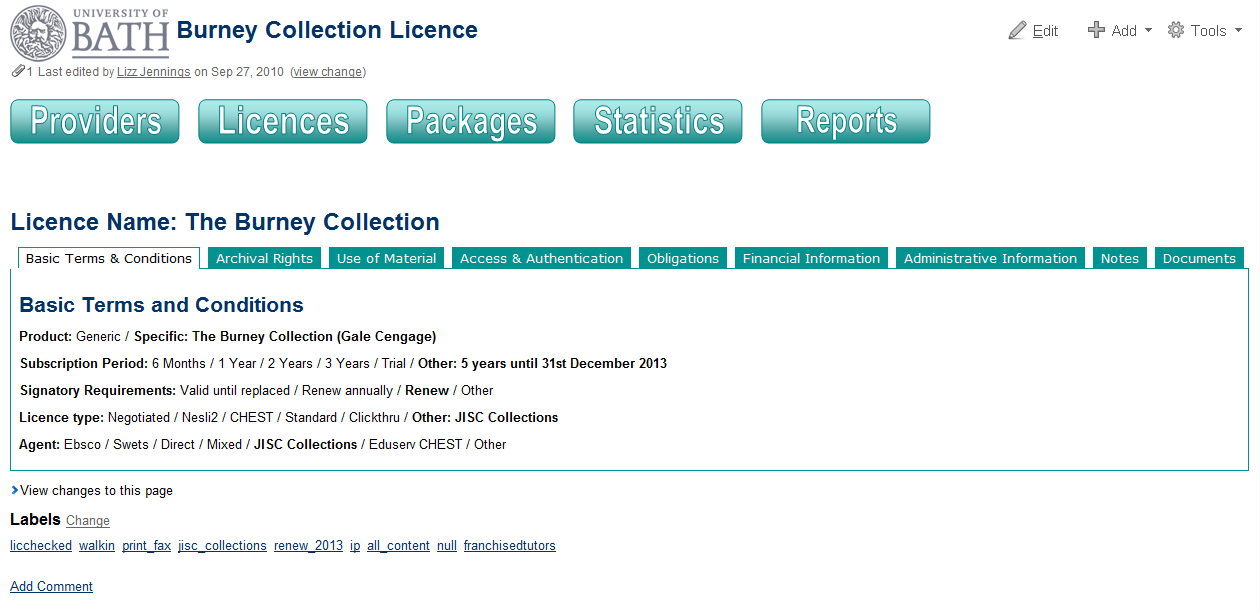

For each licence we held, we scanned or saved the document, and analysed it for generalised terms and conditions using a pro forma, designed to extract those pieces of information which were interesting to us. The form was based on the ERMI licence data elements list [1], but simplified considerably to ensure the resulting tables were not unwieldy, nor the process of analysis too time-consuming. This was then transferred to the wiki page, in a tabbed arrangement, with the scanned document linked in:

Figure 2: Example of a wiki page showing the licence terms for a resource

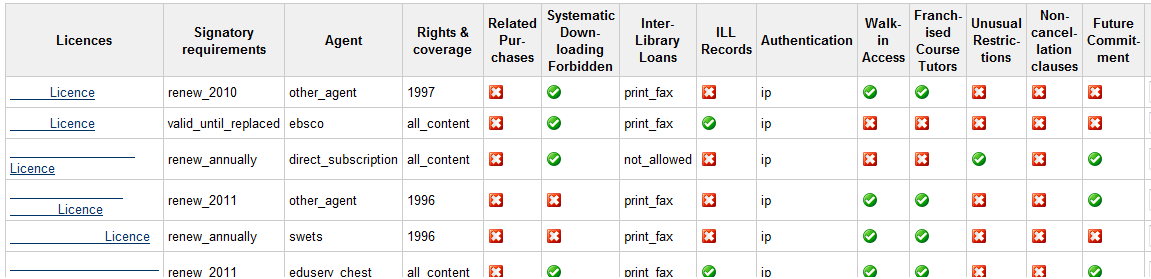

Finally, a set of structured labels was added, which were then pulled through to a summary page listing the key features of each licence:

Figure 3: Table showing an overview of licence terms

Once the licence had been analysed, a section detailing access information and titles available from that provider was created, while a home page with links to these sections, and the relevant statistics page, was also created.

This process was followed for a selection of licences, and evaluated for usability and problems. Some revisions were made, and an overall navigation system was added to improve the interaction. More licences were added, and it became obvious that even minor changes to the structure would be very slow and unwieldy to implement, as changes needed to be made on every relevant page. However, changes to individual pages are simple, and this has been particularly useful on the title pages, where the range of providers’ services can be huge.

Evaluation

The databank has been successful in several of its original aims. The accessibility of the information on the wiki has worked well, with all library staff being able to access information, even when e-resources staff are on leave. The ability to view key terms and conditions at a glance was particularly useful for some departments, and the fact that the checklist was tailored to our own particular interests helped in this regard. In all areas, the flexibility to include or omit information depending on the particular details of a given licence, meant that the databank could easily expand for larger, more complex resources without obscuring smaller or simpler ones.

The systematic collection and presentation of the information was useful, as it was easy to identify gaps in our information, and the presence of a licence triggered the investigation of the availability of usage statistics, and vice versa. It also meant that comparisons between licences were easier, as the information was held in a predictable place. The use of structured labels meant that information could be manipulated for other sections, for example a list of providers permitting the provision of single articles to other libraries as inter-library loans, a benefit noted by others such as Ruth [2].

As expected there was limited scope for producing reports from the data. As a result, the system was not able to integrate into the department’s workflows, and did create additional steps in the acquisitions process. However, the system has resulted in improved responses to enquiries and better management of changes. Additionally, as the databank uses a number of ‘macros’ which require knowledge of wiki markup to implement, it is not easily updatable by those outside the e-resources section.

Walk-in Access Information

The wiki databank provided minimal information about walk-in access, but was sufficient to begin the process of assessing our resources, as we could quickly discount those resources which did not permit guest user access, and were able to access licence information for those which did. As a result, the analysis of licence terms was made easier when the project came about, and we were quickly able to determine suitable resources. In addition, the list of service providers set up in EZproxy, through which we were providing the technical part of the solution, fed into the data collection process, and we were able to add a large number of additional resources to our databank on the wiki as a result.

Conclusions on Use of a Wiki

The use of the wiki as an electronic resources management system has been successful, and has contributed to improved information control and a deeper understanding of the resources to which we subscribe. It does not have the sophistication of a commercial system, but is adequate for our current needs. It is embedded in our existing system, which ensures it is used regularly, and is flexible enough to store relevant information to the level of granularity required by each resource. The lack of reporting functions and inability to integrate directly with workflows are the major drawbacks.

Regardless of the system chosen, time and expertise to analyse licence terms was necessary, and by using a wiki-based system, we were able to gather the information and store it systematically at very low cost. The information gathered saved time and improved the quality of responses both to enquiries and ongoing activities such as the walk-in access project.

The Solution: Facilitating Access to Licensed Material

Using OPAC Terminals

In December 2007 UCISA published a Best Practice Guide on Higher Education Access to e-Resources in Visited Institutions (HAERVI) [3]. This made recommendations for facilitating access to e-resources to students and researchers visiting from other institutions. Some of the advice given in the guide is also relevant to the problem of facilitating access to visitors who are not affiliated to a Higher Education institution. The technical solution we have achieved is similar to the “locked down kiosk facility” suggested in the HAERVI guide.

We did not want to provide computer terminals which are dedicated to walk-in visitor access, largely because of the space they would occupy, a reluctance to engage with authentication/login administration requirements and the cost of maintaining them; but also because we did not want students seeing terminals in the Library which they cannot use, given the pressure on student computing provision. We also wanted there to be a sufficient number of terminals available for the groups of sixth formers visiting from local schools and for them to be available 24/7 to match our opening hours. We therefore made access to e-resources available on the 20 existing dedicated catalogue terminals (“OPAC terminals”) which are located on four floors of the Library.

The catalogue terminals were originally set up as kiosks, providing access only to the library catalogue in a locked-down Web browser, so all that was required was to extend access to the limited set of Web sites now identified as being available for “walk-in access” under the terms of the licences. The catalogue terminals are Sun Ray thin clients, which connect to servers running the Solaris operating system and display a browser in an X-windows session. The Opera browser was used originally, because this has a kiosk mode built in, which means the browser window can be made to run with many of the functions disabled, and a ‘whitelist’ of URLs can be set [4]. However, one problem with Opera’s implementation of this feature is that if a user follows a link to a URL which is disallowed, nothing appears to happen at all: there is no indication to the user that the link isn’t working because it has been disallowed. As it happens, when we started investigating the technical solution we found that Opera was no longer supported on Solaris. We therefore found an alternative solution which provided some benefits over Opera: an add-on to the Firefox browser named OpenKiosk, which was commissioned by Brooklyn Museum [5]. OpenKiosk has a similar URL whitelisting facility, but instead of simply refusing to load a page which is disallowed, it redirects to an alternative page in which we can advise the user as to why access to the resource has not been granted.

Figure 4: University of Bath Library, first 24/7/365 HE library in the UK

The Web sites on which the e-resources are hosted are not themselves listed in the OpenKiosk URL whitelist. We use an existing service for providing authenticated access to remote Web sites: EZproxy [6]. The addresses of the EZproxy servers were added to the OpenKiosk whitelist, and EZproxy controls access to the e-resource Web sites.

The primary purpose of EZproxy is to enable members of an institution to access remote sites to which access is controlled by IP address. IP address is the most commonly used method of authenticating access to publications licenced by libraries. This makes it very easy for the members of an institution to access resources while they are using a device (PC, laptop, tablet, smartphone) connected to the institution’s network. EZproxy provides a simple mechanism to allow users whose device is not directly connected to the network to access the Web sites. What makes EZproxy “easy” is that the user does not need to configure their device or browser in any way. EZproxy fetches Web pages and rewrites the URLs in the page so that they point to EZproxy server rather than to the publisher’s server. So to the user’s browser, the Web site appears to be hosted on a server on the institution’s network, and also to the publisher’s Web site the requesting client appears to be hosted on the institution’s network.

Access to resources via EZproxy must be restricted to members of the institution, and it offers numerous methods to authenticate and authorise users. Typically users will be required to log in using their institutional username and password and be authorised by a lookup against an LDAP-compliant directory. One of the methods of authentication is by IP address, known as ‘autologin’ because the user doesn’t have to provide credentials. Because a ‘walk-in’ user is using a browser running on one of the Sun Ray unix servers, EZproxy can be configured to recognise that a login request is from one of those servers by its IP address and automatically start a session.

EZproxy allows Web sites to be placed in groups, so that access to some resources can be restricted to a particular set of users. We have used this feature to divide the resources into one group which can only be accessed by members of the institution when they have logged in, and another group of Web sites which can be accessed by ‘autologin’ users as well. Just as the OpenKiosk Firefox extension redirects the browser to an alternative Web page, when an autologin session attempts to access a resource to which they are not entitled, EZproxy redirects the browser to the same Web page which explains why access has been denied. This means that EZproxy is used to maintain the configuration of e-resource Web sites for the two different purposes of facilitating access to members of the university when off-campus, and to walk-in visitors to the Library.

Because EZproxy controls access to Web sites by host or domain, if two resources with different access conditions were hosted on the same site we would not be able to grant access to one but deny access to the other. We have not come across this situation, however.

EZproxy provides a menu of Web sites in its configuration which we have used to show the definitive list of resources which can be accessed by visitors. However it is not expected that users would want to select a resource by publisher or database name, but to find a specific book, article or other type of document in the catalogue and follow the link straight to that document. We have not found a simple way to indicate within the catalogue whether a document can be accessed, the user simply has to try their luck.

Within this setup there are no options for the user to print, e-mail or download a document. We would like to be able to offer at least one of these options, but as it stands users are at leisure to read the resources on screen and we put no time limit on use of the terminals.

Conclusions

In general terms, this approach has been a success. We have provided access to licensed resources wherever possible to visitors to the institution. The time and expense of this solution has been relatively low and its impact on, for example, school visits has been very much appreciated both by the students and by library staff. We continue to request visitor access from publishers when licenses are renewed and to provide instruction for visitors regarding how they can access our permitted e-resources. We are looking closely at collecting usage data for walk-in access, especially in the light of possible moves by publishers to linking usage to pricing and the possibility of our cost per download figures, on which we base our on-going renewal decisions, being skewed by visitor access figures. For the moment, however, we will continue to allow access to our licensed e-resources where we can.

References

- Jewell, T.D., et al., 2004. Electronic resource management: Report of the DLF ERM initiative. Washington DC: Council on Library and Information Resources.

- Ruth, L.B., 2008. License mapping for ERM systems: Existing practices and initiatives for support. Serials Review, 34(2), pp. 137-143.

- HAERVI guide, UCISA http://www.ucisa.ac.uk/publications/haervi_guide.aspx

- Opera: Kiosk Mode http://www.opera.com/support/mastering/kiosk/

- OpenKiosk add-on https://addons.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/addon/open-kiosk/

- EZproxy http://www.oclc.org/ezproxy/

Author Details

Kate Robinson is Head of Academic Services within the University of Bath Library. She is responsible for the subject teams, their teaching and collection development, the institutional repository and the Library's reader-facing services. Kate will be taking up the post of University Librarian in August 2012.

Email: e.jennings@bath.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.bath.ac.uk/library/

Lizz Jennings joined the University of Bath Library as the Information Librarian for E-Resources in 2008 and chartered shortly afterwards. Her background has taken in workplace, public and prison libraries, but her current interests include usage statistics, wikis for e-resources and resource discovery.

Lizz has recently achieved an MSc in Information Management from The Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen. She is also an active member of the CILIP Career Development Group, and currently chairs the CILIP South Western Division.

Laurence Lockton has been Systems Librarian at the Library of the University of Bath since 2002. As well as the day-to-day administration of the Symphony library management system, he has been responsible for the implementation of systems for resource discovery and linking, remote access to electronic resources, campus cards and door access control, printing and photocopying, and numerous others.

Previously he worked for Sirsi Limited, providing support, implementation and training for the Unicorn library management system.