Engaging Researchers with Social Media Tools: 25 Research Things@Huddersfield

Graham Stone and Ellen Collins investigate whether 25 Research Things, an innovative online learning programme, could help researchers understand the value of Web 2.0 tools.

This article explores whether an online learning course can help academic researchers to become more familiar with social media tools, and seeks to understand how they can put them to use within their research and teaching activities. It does so by considering the development, implementation and evaluation of a pilot Web 2.0 course, 25 Research Things, an innovative online learning programme developed at the University of Huddersfield, which gives researchers a structured way to engage with selected Web 2.0 tools. Based upon previous work undertaken at Huddersfield, 25 Research Things was the first online course in the UK to follow on from the 23 Things [1] concept in order to specifically engage with researchers about social media tools and technologies.

The programme ran in two cohorts and was hosted via a WordPress blog. A number of Web 2.0 tools were introduced each week and the participants or ‘Thingers’, ranging from 1st-year PhD students to professors, were given specific tasks which encouraged them to experiment with the aim of helping them to interact with, and to assess the value of Web 2.0 tools and technologies. All participants established and maintained a blog of their own to report on their experiences with each tool. This approach helped to build a supportive community, with participants commenting on each other’s blogs.

Background

O’Reilly [2] cites the bursting of the dot.com bubble in late 2001 [3] as a turning point for the Web and the introduction of the concept of Web 2.0, coined in 2004 by Dale Dougherty, Vice President of O’Reilly Media Inc. One key concept of Web 2.0 was a move from passive use of the Web to one of co-operation and participation where users add value to Internet services such as wiki style collaborative editing. By 2009, O’Reilly and Battelle [4] argued that there were many clear-cut examples of social media use from business decisions based on customer tweets to the Obama presidential campaign; and that ‘(t)he Web is no longer an industry unto itself -- the Web is now the world’.

The increasing presence of Web 2.0 in everyday life has prompted several investigations into its usage within academic communities. Prensky’s work [5] posits a difference between ‘digital natives’ and ‘digital immigrants’, arguing that, ‘…Digital Immigrant instructors, who speak an out-dated language (that of the pre-digital age), are struggling to reach a population that speaks an entirely new language’. A two-year ethnographic study of the student research process, undertaken by ERIAL [6] has tried to explode the myth of the ‘digital native’ by implying that just because today’s researchers have grown up with technology does not mean that they know how to use it to its full advantage and that more information literacy skills were required. Indeed, Bennett, Maton and Kervin [7] argue that, ‘…much of the current debate about digital natives represents an academic form of moral panic’. White and Le Cornu [8] suggest an ‘accurate representation of online behaviour’ to Prensky’s Digital Natives and Digital Immigrants in their ‘Visitors and Residents’ continuum, which argues that individuals move along the continuum rather than starting out as visitors and then becoming residents. Snee [9] has also examined some of the unique pressures upon academic researchers which may limit their uptake of social media, including ethical issues in social science research.

In 2007, the development of Web 2.0 technologies was investigated for Jisc [10]. In its conclusion, the report posed a number of issues and challenges to UK Higher and Further Education, not least the use of Web 2.0 technologies at the time, stating that although there was some use of these technologies [11], ‘too many researchers see the formal publication of journal and other papers as the main means of communication with each other’. In addition, Harley et al. [12] found that traditions such as peer review override the new ‘opportunities’ afforded by Web 2.0.

There is evidence that researchers have moved from complete scepticism about social media to occasional use [13]. A 2011 study of 2,000 researchers [14] has shown that social media is used at all stages of the research process from the identification of research opportunities to the dissemination of results. However, there is also evidence that take-up of social media is still restricted to a relatively small group of enthusiasts [13]. The low take-up of social media may be down to the technologies on offer at institutions being inadequate or inappropriate to research student needs. Alternatively, it may be because institutions’ current methods of engaging with researchers regarding social media is ineffective, with researchers preferring to turn to their peers for help [15]. Many have stated that they were more likely to use social media if their peers were more accepting of this medium [16], indeed Weller [17] argued that, ‘[f]or community-based approaches to become widespread in education and training, there needs to be a market pull for such learning experiences’. However, many scholarly societies have themselves become increasingly accepting of social media and are keen to point out their participation [18].

The overall picture is one of researchers demonstrating interest in these new tools, while being as yet unsure as to how they can be used to best effect. Policy-focused research reports, such as that undertaken by RIN [13], have recognised this, and argue that library and information services can be an important resource for researchers seeking to improve their understanding of Web 2.0. But it is not clear that librarians themselves have fully engaged with the opportunities offered by social media. One study found that 54% of librarians see no academic value to social media, and that while they may, for example, create a Facebook page, they spend very little time on the updating and maintenance that is required to achieve meaningful engagement with users [19].

Certain university library services have recognised that their staff need a better understanding of Web 2.0 tools and services, and have developed training programmes to facilitate this. Chief among these are activities based upon the ‘Learning 2.0’ model [20] developed by the Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (PLCMC). This methodology was based upon Abrams’ [21] suggestion that, by incremental learning and self-discovery, learners could increase their knowledge in small steps, and that this was an ideal way of learning about social media. Learning 2.0 was aimed at encouraging staff to learn about the new and emerging Web 2.0 technologies that many of the public libraries users were already familiar with in order to better serve PLCMC's mission; ‘Expanding minds, Empowering individuals and Enriching our community’. Blowers adopted a ‘steal- these-ideas’ approach by licensing the programme under Creative Commons.

Learning 2.0 and the ‘steal- these-ideas’ approach are practical extensions to Weller’s concept of learning objects and ‘adoption through succession’, where objects are reused and modified by the community [22]. In this case the ‘community of practice’ [17] is both the programme cohort, via blog comments, and the library community, via a series of re-writes and updates on the original idea.

Blowers’ Learning 2.0 approach uses blogging as a way to encourage participants to create ‘a distributed debate’, that is, bloggers posting comments on other blogger’s postings [17], Kirkup describes the recent literature about the usefulness of blogging for students ‘as a reflective journal, as a notebook to record events and developing ideas, as an aggregator of resources, and as a tool for creating community and conversation with fellow students’ [23].

Nearly 500 libraries across the world have adapted Learning 2.0 for their own workplace [24]. The University of Huddersfield was one of the first Library 2.0 programmes in UK Higher Education [25].

25 Research Things at the University of Huddersfield

The success of 25 Things for library staff at Huddersfield, and the findings of the RIN report (among others), which suggested that librarians and information professionals should play a more prominent role in helping researchers to explore and make use of social media, led to the development of a new Learning 2.0 programme: 25 Things for Researchers. The technique also reflects the importance of peer support in ensuring researchers engage effectively with Web 2.0 tools [13][15], creating a small community of people who can help each other with the tasks that they are all undertaking and allowing more experienced participants to pass on their skills and insights to more recent adopters.

When deciding on the content of the course the authors looked at the original Huddersfield 25 Things course for library staff. Findings from the RIN report were also taken on board, for example, the report found that Facebook was not seen as a relevant tool for research.

25 Research Things was written as a blog and loaded onto a local installation of WordPress [26] in advance. The Things were grouped into themed weeks (table 1). The first task for ‘Thingers’ was to create their own blog, even after the course, a number of these blogs are still being used as researchers ‘open research’ blogs.

Week | Themes | Tool |

1 | Survey Blogs | Bristol Online Surveys WordPress |

2 | Blogs & RSS Feeds

| Technorati Google Reader |

3 | Organising your favourite content

| Diigo LibraryThing Mendeley CiteULike |

4 | Social Networks

| Lanyrd |

5 | Sharing content you created

| SlideShare Prezi Google Documents Creative Commons |

6 | Images

| Flickr Mashups Online Image Generators |

7 | Play week | MyExperiment or arts-humanities.net Wikipedia |

8 | Audio-Visual

| You Tube Podcasts |

9 | Reflection

| Bristol Online Surveys WordPress |

Table 1: Themes covered in 25 Research Things

The objectives of the course were to:

- assist researchers to make sense of the Web 2.0 tools and services available to them

- provide a programme to help researchers interact with Web 2.0 tools and technologies

- assess the level of awareness of Web 2.0 tools and technologies in early career postgraduate research students within the University

- support the University Strategic map by strengthening and enhancing its research capability

- foster practical implications of the RIN research

Each Thing was described in an informal way using streaming media and Wikipedia definitions to help explain each concept. ‘Thingers’ were encouraged to have fun when discovering each Thing. However, this was then brought back to the research agenda in order to keep the overall focus of the course.

An example of this was the ‘Social Networks’ week, which started out by looking at Twitter by encouraging ‘Thingers’ to follow each other, and ended with a suggestion for a serious use of Twitter as a method for following conferences.

The course ran from November 2010 to January 2011; it was then edited and re-run from January 2011 [27]. Participants in both cohorts were given the option of blogging anonymously if they wished. It was felt that this might encourage participation in those who were very new to social media. Each blog was added to the 25 Research Things blog in the ‘blogroll’ and ‘Thingers’ were actively encouraged to read other participants’ blogs and to comment. The project authors were also on hand to help with any problems the participants may have had, and to post on the blogs too, with words of encouragement and support or to enter into some of the discussions.

Methodology

In order to evaluate the success of the course, we used two main forms of data collection. The first was a pre- and post-course questionnaire, run with each cohort of participants. The second was the blogs themselves. A key part of the methodology for 25 Research Things was asking participants to reflect upon their experiences, behaviours and practices as they explored the new tools and techniques, and expressing this publicly on a blog. This represented a very rich source of data on researchers’ feelings about the course, although with some limitations, as discussed below.

16 researchers created blogs for the first round of 25 Research Things, and 21 did so for the second round. Of the total 37 participants, 28 completed the initial survey, and just 8 completed the final survey: this perhaps reflects the low completion rate for the course itself. For this reason, we have used the initial survey to identify characteristics and backgrounds of the various participants, including their familiarity with Web 2.0, but relied on the blogs to understand their experience of the course: the final survey has not been used at all in the analysis which underwrites this article.

The blog entries were coded by the two authors, working independently and using a grounded theory approach whereby important themes were allowed to emerge from the literature. This approach carries risks: not least, that the subjective interests of the authors will tend to influence the types of themes they observe within the data and subsequently emphasise within their presentation of the research findings. We sought to limit the effects of this bias by having the two authors code the findings independently: because they are from different backgrounds (policy/research and academic librarianship) they were able to bring different perspectives to the data and thus identify themes that are not the product of just one set of interests or preoccupations. Nonetheless, as with all qualitative research, this report remains simply one interpretation of the data. Since all the blogs are in the public domain, it will be entirely possible for other researchers to replicate our study and challenge our findings, if necessary.

There are other limitations to our methodology. As has been noted, only a small proportion of the participants actually completed the course: since our methodology involved analysing blog posts, those who did not finish the course will be under-represented within our findings. Although some of them did use their blogs to chart their struggles and eventual decision to give up, others simply disappeared without trace: we will not have fully captured their experience. The small scale of the project would also be a significant limitation if any attempts were made to claim that it can fully represent a wider population. We make no such claims: rather, we offer it as an example of one intervention which made some progress in engaging academics with social media tools, and consider the success of this specific project. Participants were not informed that their blogs would be used as part of the project evaluation. We considered the ethical implications of this, but concluded that, since the blogs are in the public domain, it was an acceptable approach. Informing the participants that their blogs would form part of the evaluation might have affected what and how they chose to post, and it was important that the blogs represented an honest reflection of their experience. Of course, a risk remained that they would shape their posts to reflect their perceptions of our ‘desired’ outcomes – particularly given that we were active commenters on their blogs: as with the ‘dropout’ bloggers, it is likely that our analysis over-emphasises the positive experiences and under-represents the negative ones.

Findings

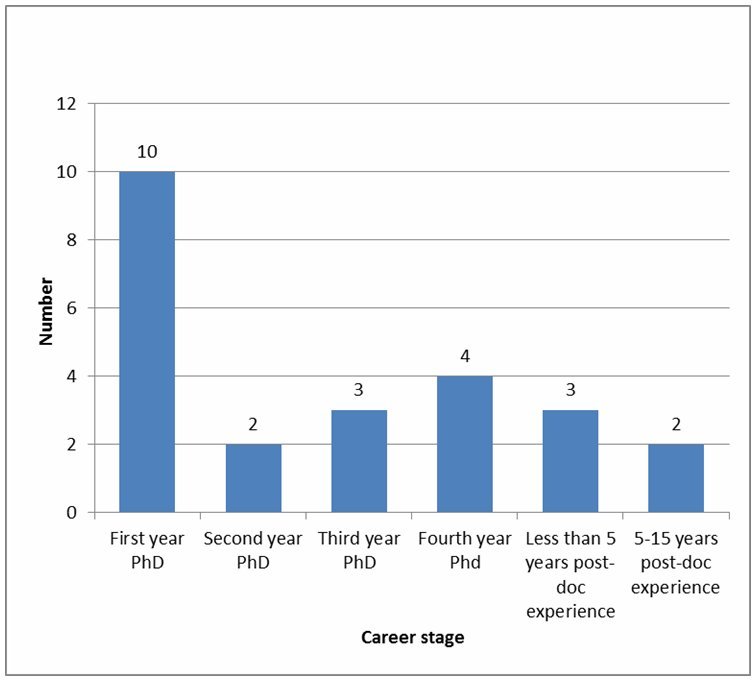

As Figure 1 shows, almost half the participants in the project were first-year PhD students. This probably reflects recruitment strategy, which focused heavily upon promoting the course in the Postgraduate Research (PGR) induction process and via the PGR email list. Overall, 19 of the 24 respondents who answered this question were PhD students.

Figure 1: Career stage of project participants

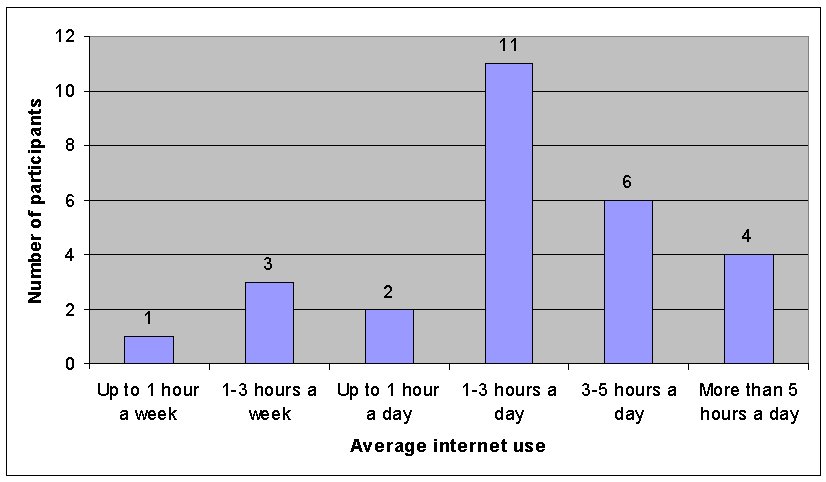

Most participants were familiar with basic Internet and computing, and used these skills on a regular basis. Figure 2 shows that the most common average internet use was 1-3 hours a day, and 23 out of 27 participants who responded to this question used the internet on a daily basis. Furthermore, two-thirds of the participants rated themselves as either ‘confident’ or ‘very confident’ with computing and IT in general.

Figure 2: Participants’ average use of Internet

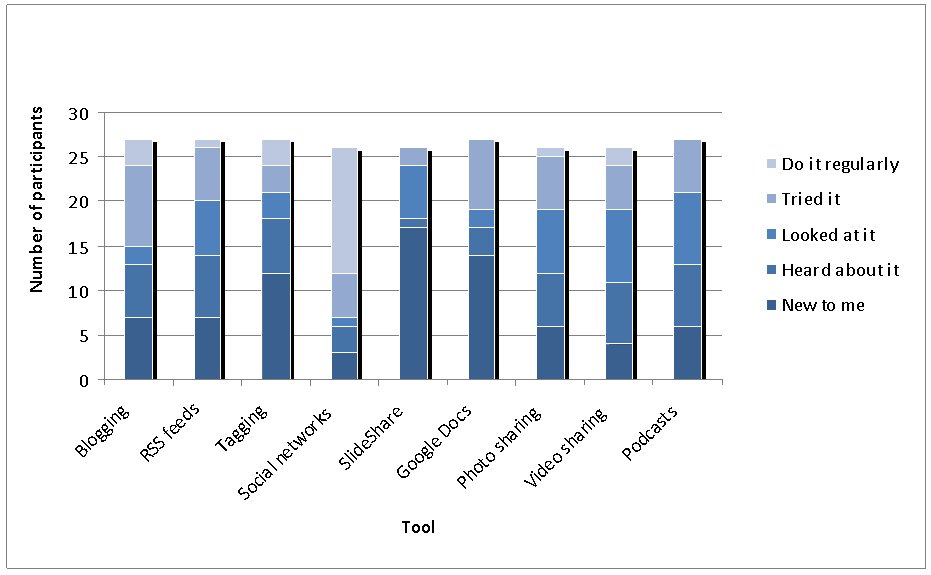

However, researchers’ experience of specific Web 2.0 tools and technologies was much more varied (Figure 3). This can probably be ascribed to the high recognition of social networks such as the ubiquitous Facebook. In other areas, however, specific named services achieved lower recognition than general themes for research. Also worth noting is the low number of researchers who are aware of tagging, as this is becoming an increasingly important way for researchers to organise and make visible information on the Web [28][29].

Figure 3: Participants’ experience with specific tools

At the start of the course, half the participants expressed a desire to improve their existing skills and learn more about these technologies. 15 of the 28 respondents were seeking to use Web 2.0 technologies within their work; either learning completely new skills, or understanding how the tools they use in their social lives might benefit their professional practice, in terms of both research and teaching. Several participants saw these tools as new ways to connect with people -- building professional networks and communicating their research outcomes. A few participants mentioned specific tools that they wanted to understand better; blogging was the most prominent among them. Two of the participants mentioned the need for support and guidance as being important factors in their decision to participate in the course.

As part of each week’s task, participants were asked to record their experience with Web 2.0 tools on their personal project blog, reflecting in particular upon whether they could see any value in continuing to use it. In addition, the final task was to reflect upon their overall experience of the course, exploring the problems they had faced and the tools they had particularly enjoyed. By reviewing participants’ experiences and preferences as expressed in their blog posts, we can gain an insight into the overall success of the course in meeting both the project aims and the individual researchers’ expectations, remembering of course the limitations outlined in the methodology section.

The next section draws on the project blogs to explore evidence in relation to these aims and expectations. Each theme can be identified in more than one blog but few, if any, can be identified in most of them. As we have said before, we make no claims to overall representativeness. The participants have all had different – and in some cases contradictory – experiences, and our representation of the findings reflects this.

Evidence from Project Blogs

The course clearly succeeded in its aim to introduce researchers to new tools and techniques. In some cases, these were tools that they had never used before:

‘I really have learned a lot, discovered things I never thought would be useful in my research and signed up to things I probably would never have found myself without this course’.

In other instances, researchers had another chance to re-examine (in a more structured way) tools that they had previously experimented with, but had never fully understood or integrated into their research activity:

‘Most of what was covered in 25 Research Things I was very aware of and had tried, but perhaps not as an active user. So it was refreshing to revisit many and have another go’.

‘It is as if suddenly I have got the hang of the language in a foreign country, and rather than being surrounded with meaningless noise which I simply pass through, oblivious, I can hear that people are trying to attract my attention’.

In several cases, the researchers found that social media tools were more valuable than they had expected:

‘I am surprised at the amount of up-to-date material on Wikipedia. Just found a really interesting article in the references as well’.

‘I have joined Twitter (which I hate to admit is a lot better than I thought it would be)’.

The course’s focus upon academic applications of social media was important for many participants, giving both legitimacy and value to the course activities. Indeed, the most popular tools were the ones that participants could see would solve some enduring research problems, often related to information management and sharing. Google Docs was seen as a useful tool for collaboration:

‘I’m working on a joint grant application with people at another university and I know we are about to get to the problem of version control on the documents we need to prepare…this seems a good way of doing that’.

‘I have always suffered from the problem of having documents with many versions which is sometimes frustrating when working in a team or on research with one or more partners. So I think Google Docs is a good solution for this issue’.

Diigo and Mendeley generated considerable enthusiasm among researchers, who particularly valued the ability to organise and annotate documents electronically. This perhaps reflects the increasingly peripatetic research practices of many academics.

[On Mendeley] ‘JOY AND JUBILATION – I now have a system on computer that I can use to annotate PDFs rather than take copious handwritten notes. In addition this system will immediately give me an overview of what I have read and from where’.

[On Diigo] ‘It’s amazing. I can now highlight and add sticky notes to any Web page I visit. So when I go to it again I’ll be able to see exactly which bit of that page was useful. I hate to admit it but this may be one of the most brilliant ideas I’ve ever come across’.

Other participants focused more upon the possible teaching applications of the tools they were using. Prezi was particularly popular for this:

‘I’ve just converted a PowerPoint presentation on travel writing into a Prezi ready to unleash it on unsuspecting students next week. I must admit, it looks a lot more exciting and less pedestrian than the usual lecture presentations’.

‘Prezi looked impressive. I might well try to transfer one of my lectures into Prezi format. I found that the best ones were quite sparse in detail and I like that for teaching and learning because it encourages students to think for themselves’.

Some participants took this further, resolving to use course content or techniques (as opposed to the tools showcased) with their students. The Commoncraft videos went down well with most participants, and one suggested that he or she would use it with students. Another felt that the course process would be useful for a particular group of students:

‘The format of the blog with tasks linked to other blogs responding to tasks has been really good and I am now just about to replicate this with my teacher trainees. They are due to go out on block placement so we won’t see them for six weeks and we had always intended to set up online activities for them. The platform of choice by default was to be Blackboard but I have chosen to use blogs and [I am] going to trial the same model with minor differences in terms of the workload’.

Finally, several participants noted that social media helped them to stay up-to-date with recent developments at the University of Huddersfield, either in their discipline or in Higher Education more generally.

‘One useful thing about Twitter – Hudds Uni Graduate Centre tweets have put me in touch with some very interesting blogs by other researchers further down the road on their PhD journey’.

‘I really like it when keynote conference presentations are available on Slideshare as it gives you the gist of what was talked about without the expense of being there’.

[On LinkedIn] ‘I think it would be useful if you were looking for a new job, so with the HE cuts ahead of us, it probably does no harm to get involved and build your network, so that you are established if and when you really need it’.

All these responses show the importance of 25 Research Things in helping academics and researchers to see the hidden potential of tools that they had previously considered unrelated to their work – or, indeed, had not considered at all. But an equally important outcome of the project was to help researchers reject tools, based on experience rather than uninformed perceptions about usefulness. Many participants, perhaps representing White and Le Cornu’s [8] ‘visitors’, recognised the value of the course in helping them to understand what they did and did not find useful:

‘For me a lot of these ‘tools’ are just distractions. But if I only use two or three of them long term it will be worth it I guess’.

‘Having an unenthralled week with this…But looking around allows one to make choices so fine’.

In some cases, this simply confirmed existing opinions about usefulness:

‘Twitter (which I still don’t understand by the way, even this course couldn’t change my mind about that)’.

In others, researchers made decisions following their experiments with tools that they had not previously tried:

‘Librarything was ok – I was completely egotistical and only added books by me to my library! I don’t think it is something that I would use again, I have to say’.

Researchers mused upon what had led them to reject specific tools. In general, a tool would be rejected if it was not intuitive, did not slot easily into their existing work habits, or (as mentioned above) did not solve an existing work-related problem. However, even rejections need not be final:

‘At this point I can’t see any benefit of Mendeley for me, though it might change in the future’.

This participant recognised that his or her research needs may change, and has mentally bookmarked one tool as a solution to possible future problems.

Participants were prompted to reflect on their experience of the course in the blogs. Online learning was a new process for many of them, and clearly they enjoyed the process – in particular, the opportunity to interact with colleagues that they perhaps did not know before the course began. This was evident throughout the process as participants commented on each other’s’ blogs, both in the comments section and in their own posts:

‘My fellow course members have been great and I’ve enjoyed reading their blogs – some have made me laugh out loud. It’s also shown me how an on-line course can work so well’.

‘I have really enjoyed the little community that we have built here and look forward to finding out more about people who work at Hudds Uni, which was one of my aims for the course’.

But there were also some challenges for participants, and it was clear from the high proportion of non-completers that the course did not meet everyone’s needs. One particular challenge was catering to the needs of complete novices and relatively experienced users of social media with a single set of activities. One participant clearly felt this to be a problem:

‘I am feeling a little out of sorts with this when I read others’ work on the blogs. I am just past week two and although I can get myself around this site, it feels like being a dog with one leg’.

As we have mentioned, the experiences of those who dropped out of the course are under-represented in this study, and it is possible that this attitude was more widespread than the blogs themselves suggest: if bloggers chose not to blog about their problems but simply to abandon the course (as some did), we will not have captured their reasons for doing so.

Participants also recognised that their level of familiarity with specific tools affected the time they spent each week. As one said:

‘It was a lot of hours, particularly in the first few weeks where there were lots of new things that I spent a long time thinking about and setting up – in later weeks we were looking at things I knew about so it wasn’t so intensive for me’.

And while participants appreciated the comments and input of their fellow bloggers, the support offered by the project team was seen as a bit more patchy, with both bad and good experiences recorded in the project blogs:

‘There was lots [sic] to do each week and not much backup. I’m sure my experience of blogging via the MSc in E-learning will be much better due to more structured tutor and peer support’.

‘I got stuck this week, big style. I gave up after an hour and had to ring Graham, who I must say was very helpful and incredibly patient’.

Good technical and personal support is clearly very important to researchers who are struggling with a number of new ideas, systems and techniques.

Discussion

Both the introductory survey and the blogs suggest that researchers are primarily interested in the value that this course can add to their professional lives. This is particularly evident when considering the tools that researchers suggested they would continue to use after the end of the course. Tools such as Diigo, Google Docs, Mendeley and DropBox were the most popular. These tools help researchers to curate and store information sources or share and collaborate on their own work. It is interesting to note that DropBox was not included in either course, but was recommended by one of the cohort [30]. However, researchers clearly enjoyed some of the less research-focused uses of tools, suggesting that the combination of serious applications and more light-hearted suggestions was important to the success of the course.

The course was designed to focus upon the benefits to research activity. However, many of the participants who also had teaching and learning responsibilities identified ways that the tools could help with that part of their work. This encouraging response shows, first, that participants were really engaging with the techniques and reflecting upon how they could integrate them into different aspects of their professional lives, and second, that the scope of the course could be considerably greater than originally anticipated. Participants also saw the value of networking through social tools, using them to stay up to date with developments in their field, their wider discipline, their institution or in academia and Higher Education policy. This is something that had been anticipated, but perhaps could be drawn out more in revisions of the course.

Another important outcome for a number of participants was not so much identifying tools that would be immediately useful to them, but rather to identify those which they could happily do without. It seems to have been important to participants that they had an opportunity to try tools in a relatively structured way and reject those for which they could not find a use. Many commented that if they finished with only two or three tools which continued to be useful, they would consider the course to have been worthwhile.

As the introductory survey showed, most participants were experienced internet users, and most rated their skills with computers quite highly. However, familiarity with the specific tools was mixed, and this clearly showed as the course developed. Some struggled with exercises that were considered to be relatively simple, sometimes for reasons that had not been anticipated: for example, one participant could not set up a Google account because (s)he did not have a mobile phone. The team tried to graduate some of the tasks, giving participants an opportunity to stretch themselves, but it may be that in fact some of the tasks needed to be pitched at a more basic level to ensure participants felt they were keeping up.

On the whole, participants enjoyed the process of the course, and felt in particular that the support of their peers helped them to engage more effectively with the tools on offer. A nascent community did begin to share experiences and tools, and to comment on each other’s’ blogs, and this was evidently important to researchers, as shown in some of the comments outlined above. This said, many commented that they would have welcomed more input from the 25 Research Things team. On reflection, the team lost ‘the educational narrative’ and should have been more visible. As Weller [22] states:

‘The educator’s role is significant here, in creating a dialogue that helps students to draw connections among the learning objects and incorporate them into higher-level themes’.

This would have helped to identify and encourage those who needed it and may also have resulted in a higher completion rate.

Conclusion

As a pilot and proof of concept, 25 Research Things was a success. The small sample showed that some researchers are interested in using Web 2.0 tools to enhance their professional practice, and demonstrated that an online interactive learning course is an effective way to help them do so. The course helped them to distinguish the tools that were useful now from those that would potentially be useful in the future, and also to identify and eliminate tools for which they could see no use within their research activity. It also stimulated creative thinking, leading researchers to use tools in ways that were not necessarily envisaged by the course creators (for example, in teaching and learning as well as in research).

The pilot also identified some important issues that need to be resolved for a future 25 Research Things project. Drop-outs may be an inevitable feature of a course like this, where participation is not mandatory; however, there seems to be a link between dropping out and expressing dissatisfaction with elements of the course – particularly the volume of material each week, the length of the course and the lack of physical (as opposed to virtual) support.

Figure 4: Howorth & Walsh - The Informed Researcher at Huddersfield

The course will be run again in 2012/13, as part of the ‘Informed Researcher’ project at Huddersfield, which aims to build an information literacy framework for researchers at the University [31]. The project is aligned with the information literacy lens on the Vitae Professional Development Planner [32]. Informed Researcher will encourage reflective blogs and these will form part of a revised 25 Research Things programme. The new course will also incorporate a face-to-face element, so that participants can meet each other and the administrators. This may help foster the online interactions that proved an important support to participants in the first two rounds of the project, and may encourage struggling researchers to seek help rather than dropping out.

References

- Helen Leech. "23 Things in Public Libraries". July 2010, Ariadne Issue 64

http://www.ariadne.ac.uk/issue64/leech/ - O’Reilly, T. (2005), What is Web 2.0: Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html

- Jorn Madslien. Dotcom bubble burst: 10 years on. BBC news, 23:27 GMT, Tuesday, 9 March 2010 http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/8558257.stm

- O’Reilly, T. and Battelle, J. (2009), ‘Web squared: web 2.0 five years on’, in Web 2.0 summit, 20-22 October, San Francisco CA http://www.web2summit.com/web2009/public/schedule/detail/10194 html

- Prensky, M. (2001), ‘Digital natives, digital immigrants’, On the Horizon, vol.9, no.5, pp.1-6.

- Ethnographic Research in Illinois Academic Libraries. (2012) ERIAL project http://www.erialproject.org/

- Bennett, S., Maton, K. and Kervin, L. (2008), ‘The ‘digital natives’ debate: a critical review of the evidence’, British journal of educational technology. vol.39, no.5, pp.775-786.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00793.x - White, D.S. and Le Cornu, A, (2011), ‘Visitors and residents: A new typology for online engagement’, First Monday, vol.16, no.9. http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3171/3049

- Snee, H. (2008), Web 2.0 as social science research tool, British Library, London.

http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/bldept/socsci/socint/web2/report.html - Anderson, P. (2007), What is web 2.0? Ideas, technologies and implications for education, JISC Technology and Standards Watch, London. http://www.jisc.ac.uk/publications/reports/2007/twweb2.aspx

- Murray-Rust, P. (2008), ‘Chemistry for everyone’, Nature, vol.451, pp.648-651.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/451648a - Harley, D. et. al. (2010), Assessing the Future Landscape of Scholarly Communication: An Exploration of Faculty Values and Needs in Seven Disciplines, Center for Studies in Higher Education, Berkeley

http://escholarship.org/uc/item/15x7385g - Research Information Network (2010), If you build it, will they come? How researchers perceive and use web 2.0, RIN, London.

http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/communicating-and-disseminating-research/use-and-relevance-web-20-researchers - Rowlands, I. et. al. (2011), ‘Social media use in the research workflow’, Learned Publishing, vol.24, no.3, pp.183-195.

- Carpenter, J. et. al. (2011), Researchers for tomorrow: annual report 2010-2011, Education for change, London. http://explorationforchange.net/attachments/061_Researchers%20of%20Tomorrow%20Year%202%20report%20final_110510.pdf

- Proctor, R. (2010), ‘Adoption and use of Web 2.0 in scholarly communications’, Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society A, vol.368, no.1926, pp.4039-4056.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2010.0155 - Weller, M. (2007), ‘The distance from isolation: why communities are the logical conclusion in e-learning’, Computers and education, vol.49, no.2, pp.148-159.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.04.015

- Mahapatra, A. (2010), ‘Researchers in a brave new web 2.0 world’, ACS Chemical Biology, vol.5, no.9, pp.799-800. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/cb100268t

- Hendrix, D, Chiarella, D, Hasman, L, Murphy, S and Zafron, M. (2009) ‘Use of Facebook in academic health sciences libraries’. Journal of the Medical Library Association, vol.97, no.1, pp.44-47.

http://dx.crossref.org/10.3163%2F1536-5050.97.1.008 - Blowers, H. (2006), Learning 2.0: http://plcmcl2-about.blogspot.com/

- Abrams, S. (2006), ‘43 things I might want to do this year’, Information Outlook, February 2006.

- Weller, M. (2007), ‘Learning objects, learning design, and adoption through succession’, Journal of computing in higher education, vol.19, no.1, pp.26-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03033418

- Kirkup, G. (2010), ‘Academic blogging: academic practice and academic identity’, London review of education, vol.8, no.1, pp.75-84 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14748460903557803

- Blowers, H. (2006), Hblowers learning2.0Libraries Del.icio.us links:

http://del.icio.us/hblowers/learning2.0Libraries - Barrett, L. et. al. (2009), ‘Getting to know Web 2.0 tools’, CILIP update. November 2009, pp.40-43. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/6524/

- Pattern, D. et. al. (2010), 25 Research Things 2010: http://25researchthings2010.wordpress.com/

- Pattern, D. et. al. (2011), 25 Research Things 2011: http://25researchthings2011.wordpress.com/

- Vitae (2011), Digital Researcher conference 2011:

http://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers/315321/Digital-Researcher.html - Collins, E. and Stone, G. (2011), Social Citation, in Digital Researcher Conference, 14 February 2011, London, UK: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/9564

- Folley, S. (2010), My research blog: http://25thingssuefolley.wordpress.com/

- Walsh, A. and Howorth, N. (2012), Creating the informed researcher: adapting the information literacy lens of the Vitae Researcher Development Framework for local needs. In: Vitae Researcher Development International Conference 2012: Realising the Potential of Researchers, 3-4 September 2012, Manchester. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/14663/

- Vitae (2011), Research Development Framework:

http://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers/428241/Researcher-Development-Framework.html

Author Details

Email: g.stone@hud.ac.uk

Web site: http://www.hud.ac.uk/

Graham Stone is Information Resources Manager at the University of Huddersfield, his responsibilities include the library information resources budget and management of the Acquisitions and Journals and E-Resources Teams. He also manages the University Repository and University of Huddersfield Press Initiative. Graham has managed a number of Jisc-funded projects including the Library Impact Data Project and the Huddersfield Open Access Publishing project. He is UKSG Publications Officer and member of the Insights journal editorial board, the Electronic Information Resources Working Group (EIRWG), the PALS metadata and interoperability working group, the OAPEN-UK Steering Group and chair of the Jisc Collections Journal Archives Advisory Board. He is currently undertaking a Doctor of Enterprise at the University of Huddersfield, which is looking at the viability of the University Press as an Open Access publisher.

Email: ellen.collins@researchinfonet.org

Web site: http://www.researchinfonet.org/

Ellen Collins is a Research Consultant at the Research Information Network, where she has initiated, developed and managed projects for clients including academic publishers, librarians, funders and policymakers. She is particularly interested in how researchers find, use and share information, and the ways that their behaviour is changing in response to new communications platforms and business models. She has worked on a number of projects around researcher use of Web 2.0, and is currently working with several publishers to explore the research community’s aspirations around open access. She is also the lead researcher on OAPEN-UK, a collaborative research project to explore open access scholarly monograph publishing in the humanities and social sciences.